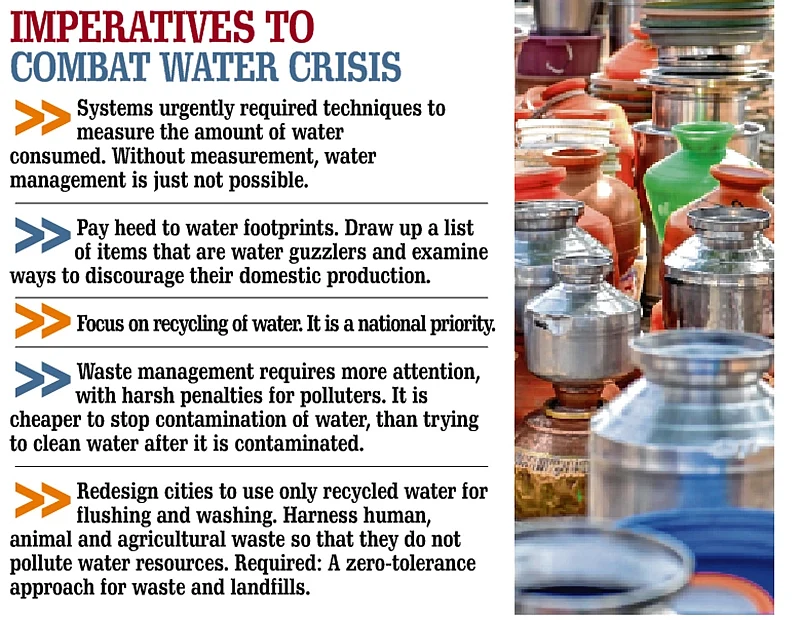

Around 9.6 per cent of India’s land is covered with water. It also has 7,500 km of coastline. Yet Indian states face a drought-like situation. It points to an utter lack of water management in the country. To highlight the importance of World Environment Day, Free Press Journal organised a panel discussion involving various stakeholders in this space. We decided to focus on water management, recycling of water and the management of waste in the country with specific focus on Maharashtra.

The panelists included (in alphabetical order) Uma Aslekar, Senior Scientist, Advance Centre for Water Resources Development and Management (ACWADAM); K P Bakshi, Chairman, Maharashtra Water Resources Regulatory Authority (MWRRA); Madhav Bhandari, Chief Spokesperson, Bharatiya Janata Party, Maharashtra State unit; Aditya Bhujle, Director, Sunrise Consultech; Ya’akov Finkelstein, Consul General of Israel in Mumbai;

Nimrod Kalmar, Deputy Consul General of Israel, Mumbai; K V Rao, Chief General Manager, Nabard; Brajesh Singh Tomar, Deputy General Manager, Ambuja Cement Foundation; and Divyang Waghela, head, TATA Water Mission, shared their view on the same. The session was moderated by R N Bhaskar with editorial support from Pankaj Joshi who writes…

Edited Excerpts:

Major issues contributing to a looming crisis

Uma Aslekar, Senior Scientist, ACWADAM: There is a vital component of water which is largely ignored– groundwater, not just in Maharashtra but throughout the country. It is time we appreciate its importance. It is documented that any public water supply scheme relies up to 90-95 per cent on groundwater resources.

Likewise, 65 per cent of irrigation supply and 45 per cent of urban water supply depends on groundwater. However, it is one of those things which get impacted from the “out of sight, out of mind” syndrome.

In this context, it is vital for all, who wish to study the current water situation, to understand two concepts. First is the concept and utility of aquifers, the basic geological unit of groundwater storage. Aquifers are complex in terms of geology and heterogeneity. One farmer may get abundant groundwater on his plot, whereas his immediate neighbour may get very little.

The second is the rainfall pattern modification, a possible link to global warming. Our data shows that the drought cycle in Maharashtra historically spanned five years – one drought situation every five years – which is now down to three years across the past decade.

There is a similar change in the rainy days – earlier we had around 45 days of strong rainfall in a monsoon which is now down to 15 days. The rainfall now is more intense – something like 100 mm in three hours.

This means rain days for crops have gone down, and likewise greater probability of water flowing away to the sea, rather than seeping into the ground. In all this, we need to take measures to manage and enhance groundwater, to manage the rising gap between supply and demand.

Brajesh Singh Tomar, DGM, Ambuja Cement Foundation: One major issue in water management is the total neglect of traditional practices. Introduction of drilling technologies and diverse government schemes have seen our traditional water management practices get sidelined.

For instance, we had a problem of excess salinity of water in the Gir region of Gujarat. Free electricity and high-power pumping had resulted in sea water entering the aquifers, making water usage in the area unsuitable for agriculture or even livestock rearing.

Here, we promoted traditional approaches accompanied with technology implementation. Today, the same land gives three crops a year, with drinking water for people and livestock.

(L to R) Aditya Bhujle, Director, Sunrise Consultech; Brajesh Tomar, DGM, ACF; Madhav Bhandari, Spokesperson, BJP; & Nimrod Kalmar, Deputy Consul General of Israel |

For the past five years, no tanker water has been brought from outside. In Rajasthan, we desilted ponds and improved the cachement area. Now, we are reviving the traditional farm pond practice, wherein some area of each farm has a pit wherein rain water is collected and used.

Ya’akov Finkelstein, Consul General of Israel, Mumbai: Scarcity of water and quality of water are global issues. My country Israel suffers most, since a third of our country is desert area. Our population has grown more than tenfold since 1948, the year of our nation’s formation.

(L to R) K P Bakshi, Chairman, MWRRA; Divyang Waghela, head, TATA Water Mission; K V Rao, Chief General Manager, Nabard; & Abhishek Karnani, Director, Free Press Journal |

Necessity is the mother of invention – we had to have some solution. Today, we have cutting-edge technologies for desalination as well as drip irrigation. We convert humidity to water and our taps supply water at reduced pressure.

Monitoring and metering – critical contours

Madhav Bhandari, Chief Spokesperson, BJP, Maharashtra State unit: Monitoring is vital. I have for long been pushing for metering, both for consumption of water in rural areas, as well as of groundwater usage and availability.

Take the case of Pune, an urban area. Given its size of population, the amount of consumption they do is seven times more than the norm. Still there are shortages. Now how can we get to the root of the problem without monitoring? Monitoring brings accountability and cost implications, else the mindset is that what is available for free can be wasted.

Tap |

Ya’akov Finkelstein: How can one work without control and measurements? It is vital. Secondly comes the need for people to be educated. Measurement must be accompanied by fee – psychologically the consumer must realise that it is a transaction, that water is not free

If you cut down on your shower time by 30 seconds, it would save around 10 litres of water. Imagine the difference such discipline across India’s population can make.

K P Bakshi, Chairman, MWRRA: Our pricing exercise till 2015 was based on surface area assessment. In rural area for 2017-20 tariff levy, wedecided to shift to volume-based assessment. The users accepted it,but the government postponed the decision.

Today there is no assessment system at farmer level, or even at the village level. There are technology advancements that have made such assessment possible.

For instance in Australia, water diversion is done remotely from the system to the farmer’s field, and commensurate charge debited to his account. Even for borewells, we can start with the horsepower (HP) of the installed machine and estimate the water that can be consumed if used for 8 hours or more. Then we can link it to the electricity consumption and get a very fair estimate.

Divyang Waghela, Head, Tata Water Mission: Water and energy have a strong correlation. Now if energy is priced and metered, water can be linked and evaluated too.

There are two aspects to this – the policy should have control, penalty and also incentives. Secondly, we need to rationalise tariff based on usage. In Ahmedabad, we started power metering system in societies and charged them on consumption. There was a drop in energy billing by 40 per cent and in wasteful consumption by 30 per cent.

K V Rao, Chief General Manager, Nabard: Speaking specifically about Maharashtra, I can assert that the Water Users Association has seen a success in implementing the metering proposal. Volumetric metering and billing has been a success in all areas where this association is present.

The flip side is that in some places we had installed meters just for monitoring, but the locals damaged them. Their logic was clear – what can be metered today can be charged tomorrow. Ultimately local support is critical.

Brajesh Tomar: Groundwater metering is difficult in rural areas, but we have seen success with participatory management (on the self-help group model) and social control.

Divyang Waghela: Our understanding and learning can be boiled down to a couple of points. Firstly, technology has to be relevant in the Indian context. Second is that we have to build an ecosystem, and that process must incorporate local culture and values. The policy of conserving, recycling and re-using water has to be robust, implementable and acceptable to the local stakeholders.

Recycling

Aditya Bhujle, Director, Sunrise

Consultech: We work a lot with German Water Partnership, which is an initiative promoted by five Federal ministries. GWP has been active in India for a number of years, and it has participated in diverse initiatives ranging from government programmes to delegations and working groups.

Our primary responsibility is implementation of technologies, and within that our other aim is speedy indigenisation of these technologies. Today the economics of recycling water are totally proven and accepted.

We, for our part, have successfully implemented a lot of solutions and those can be implemented in bigger way. So what is the hindrance? Global technology providers are not comfortable with the working environment – the current tendering process, for instance, definitely needs to be looked at.

Divyang Waghela: Our work has made us understand that actual users are the best managers, who can bring awareness into action. We have done work in 12 states across all of India.

Aditya Bhujle: Until very recently, technology and affordability did not go together on recycling projects (when one would compare it with wells and tankers). But now the project cost is getting somewhat attractive.

However, desalination projects are still somewhat expensive here, mainly because complete indigenisation is still to happen. In itself, recycling should be a priority. When we look at some industries, they have challenging effluents which are not easy to treat.

In some nations, there are economic consequences – either that factory invests in better Effluent Treatment Plant (ETP) systems or there is a statutory payout, which they must factor into their production cost.

KP Bakshi: The concept of differentiation of quality of effluent is not yet practised here, but we will definitely take it up. I would want to extend this discussion to domestic waste water as well. Prior to 2017, the policy was that the municipal body would treat the water and discharge it into the river bed, from there someone else could lift it.

We modified the policy – once you treat it, you can sell it. Farmers would be ready to buy it for agri-usage at 60 per cent of their freshwater cost. So there is an incentive for both the municipal body and the farmers.

On the industrial side, (practically) there is no incentive and the process still comes across as expensive. Maharashtra now has treatment capacity which is around 65-70 per cent of the requirement.

But even that capacity is not fully utilised (half capacity used). It is estimated that only one third of effluents generated in Maharashtra go through treatment. Corporate like Mahindra, who have practically zero fresh water usage at their Igatpuri facility, are rare.

One more aspect is that in our country, visible development still gets priority. Roads, buildings, hospitals –outlays on these will get more priority over water treatment. This is a topic which is pursued by activists, courts, or some committed bureaucrats.

Uma Aslekar: Quality of recycling is also vital, else the improperly treated water when released into the ground has the potential to damage the entire aquifer water. This has happened once in Pune.

K V Rao: What is existing and proven should be pursued anyway. For instance, the practice of rooftop water harvesting and diverting into a pit. Likewise, the practice of farm ponds is not expensive to revive. Also, recycled water can be diverted to hard rock areas so that those aquifers get a recharge.

Regulator touch

K P Bakshi: The regulatory body was set up in 2005 under an Act, promulgated by the Maharashtra government. Our staff has expertise in diverse areas—engineering aspects, groundwater, legal matters and lastly the economic understanding of whatever measure is being contemplated or scrutinised.

The main function of the regulator is to ensure that appropriate tariffs are applicable to all water distribution to and consumption by all three categories of consumers— agriculture, domestic users and industrial users.

Our other key function is to ensure distribution of water is equitable. This includes the responsibility of adjudication, and secondly in times of stress in any part of the state, we see that the stress is spread out and shared equally.

Since 2013, groundwater is also under our purview. In terms of groundwater policy, rules have been framed. Once the state election process is through, I hope that some steps will be taken in the direction of implementation. Once the policy is in place, we as a regulator will have more teeth.

K V Rao: NABARD, in its mandate of agricultural and rural development, has been looking very closely at water. For funding our approved projects, we have access to World Bank funds and we also work with companies who have Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) funds in this area. If a company is contributing a particular amount as CSR for a project, we then provide matching funds from our side.

In 1991, we started watershed development projects. The primary focus was to stop drainage of monsoon water, and allow it to percolate. Once this happens, you see groundwater recharged.

This was done with ground support from Non-Governmental Organisations (NGOs) across different states and has been very successful. The blueprint of this work has now been taken up by the government to be implemented in a bigger way.

In watershed territory, there is approximately 20 per cent area which we cannot access, because it is either over-exploited, critical or water salinity is high. Our approach to watershed project is to see that the groundwater recharge is done first, and secondly that safe delivery of the same is managed. Our projects also have to build in some element of climate resilience.

Madhav Bhandari: I have been co-convenor of the national water resources cell of the BJP for the last four years. Even before BJP came to power, we were advocating a policy of bringing all water-related work departments together.

This was part of our manifesto and this time we have indeed got a Jal Shakti Ministry which encompasses all these water-related matters. In Maharashtra, as part of the policy decision, we are going in for piped irrigation in Maharashtra, and also focusing on micro-irrigation.

Divyang Waghela: All planning has to be long-term, wherein no one should be left out. In this context, an integrated approach to water by having one ministry – Jal Shakti, to deal with all matters on this topic is a positive development.

Nimrod Kalmar, Deputy Consul General of Israel: Our government policy is oriented towards creating awareness among consumers. We had an ad campaign that ran five-six years ago, that Israel is drying out. It was extremely aggressive and there was a significant impact on water usage, even though Israel was an efficient user earlier too.

Ya’akov Finkelstein: Apart from politicians, our water department has a representation of technocrats and professionals. Today we recycle 90 per cent of sewage water for agricultural use. 50 per cent of our drinking water comes from desalination.

We have reduced the non-revenue component of water supply to 5 per cent – for India the equivalent figure is 30-40 per cent. These efforts can be applied in India too – this subject is defined as an area of strategic co-operation between two nations.

K P Bakshi: We have established a centre of excellence at Kharghar in Navi Mumbai, which commenced operations a couple of months ago. The broad mandate is to promote innovation in water management, to have progressive regulations (focussing not just on penalties but also on education) and lastly to raise awareness on the value of water.

One strong thought process among us is — data is important, it is power and must be shared. We want to have real-time data from all departments whose work relates to water—Water Resources, Water Conservation, Pollution

Control, Agriculture, Industry, Urban Development—and should be updated every 10 minutes. We are working on that and on satellite imagery. All these activities will provide much more accuracy, and will help even in other areas like flood management.

Focus areas for the future

Ya’akov Finkelstein: Co-operation can be at three levels, namely government to government, business to business and government to business. We think business to business is the best model mainly because it works quicker. An example of that is our work in the industrial area of Vapi in Gujarat. We have a project in Chennai under the government to business model.

For the government to government model, there is an assignment of creating an inclusive solution for the drought-affected Marathwada area of Maharashtra. We are proposing a 3,300 km pipeline to connect different dams and rivers.

This will allow direct flow of water to needy areas, even uphill against gravity in some places. This project which is worth USD 1.5 billion has got in-principle approval.

Likewise, we can look at offering solutions in urban waste management, desalination and water harvesting. Apart from money, policy alignment and educating people are two major support factors needed for success.

Divyang Waghela: The sustainability group of Tata Water Mission focuses on one outcome – how we can make a community self-reliant in terms of water requirement. First of all, the community should see the amount of water they utilise and whether it is justifiable or if there is an element of overuse.

Second you see demand in context of your local water resources and if there is any deficit. Third is how to bridge the deficit through optimisation on either side of the equation.

A community must understand how to manage without dependence on external sources. The moment that mindset emerges, we know we will get somewhere.

Madhav Bhandari: I come from the Konkan region in Maharashtra, which has some peculiarities. Despite good rainfall (my village gets 130 inches) there is a water shortage for a large part of the year. I am also trying to revive the traditional systems of water management, with some success in raising groundwater levels.

We have to understand and absorb three points into our way of living. The first is that we are a water-deficit state and this has to reflect in our policies, right down to our daily habits.

The second is that we are not ready to accept any discipline around water. We waste water more than we use it. Third we should understand that water should be used as a resource, not treated like a commodity. For all this to be possible, there is a need for action from media and pressure groups.

Aditya Bhujle: Water as a resource needs an integrated approach for management – users, regulators, suppliers all have to be brought in.

Lack of ownership is where the problem will start otherwise – wherever there is a breakdown or divergence from the accepted pattern of distribution and consumption, who would be held responsible? That is the ground of conflict and consequent lack of progress.

We can learn a lot from Germany in that respect – it was not long ago that they faced the problem of polluted rivers and contaminated groundwater. Now Germany has 20 per cent of the world water recycling technology market. This happens when someone takes responsibility to make things better.

Brajesh Tomar: Ambuja Cement Foundation seeks to improve the socio-economic conditions of resident stakeholders in and around Ambuja’s manufacturing sites. One of the community needs we address is water— in states such as Gujarat, Rajasthan, Maharashtra and Himachal Pradesh.

Acceptance and participation of the community are needed for such projects to succeed. We have also seen helpful government policies, especially in micro-irrigation and rooftop rainwater harvesting in Maharashtra. Meanwhile, Gujarat has a single-window clearance for micro-irrigation applications.

K V Rao: As of now water harvesting and watershed management are key focus areas, both in farm or non-farm projects. For instance, in the North-East the terrain is quite hilly wherein we focussed on spring shed development, and priority was given to crop types grown in plantation.

Ganga |

NABARD aims to refinance bankable agri-projects, for which we have found good options in irrigation as well as agri-technology proposals. We would also like to see the increase in coverage area under dry crops, or those which need lesser water.

We also focus on last-mile completion – sometimes irrigation canals are developed but because side-canals are neglected, the desired crop results do not materialise. Then we focus on the deficiency.

NABARD is responsible for the basic development and the ancillary focus areas – crop, animal husbandry or non-farm usage – all come from other sources like CSR funding. We are open to work with corporate houses. NABARD’s long-term irrigation fund started around five years back.

Today, this fund supports 99 irrigation projects (that were started three-four decades back). We have developed a mechanism to ensure these projects get completed in a time-bound manner; and mobilise resources and divert them to the individual projects.

Our Rural Infrastructure Development Fund (RIDF) is in its 27th tranche. We are responsible for disbursals of Rs 20-25,000 crore on annual basis. Funding also comes from banks, as part of their priority sector lending.

Overall we must understand that land area under cultivation is going down, but from this we have to provide for a population whose size is going up. Awareness of different programmes has to increase.

We have found that farmers by and large are responsive, entrepreneurial in nature and it is our responsibility to reach out to them. Banks want to enhance their book in this area; and corporates and NGOs are supportive. So, we believe good things will happen.