A tremor is running through the global economy, faint yet unmistakable, like the first distant rumble before an earthquake. Artificial Intelligence (AI), once the province of research labs and science fiction, has entered the fluorescent-lit world of offices and cubicles. Its arrival has stirred an old and bitter memory: the dotcom bubble of the late 1990s, when promises of boundless innovation preceded a brutal collapse of markets and livelihoods. Today, the question is no longer whether technology will change work, but how many jobs it will erase before society is ready to respond.

Unlike the dotcom era, the current upheaval is not limited to speculative start-ups or exotic shares traded by adventurous investors. The disruption is intimate and immediate. Algorithms now read, write, listen and analyse at speeds that dwarf human effort. They perform routine intellectual labour tirelessly and without complaint. What once required a small army of clerks can now be achieved by a cluster of servers. The consequence is already visible: a thinning of roles built upon repeatable, predictable tasks.

File Image |

In offices across the world, the first casualties are familiar and unglamorous. Administrative and clerical work is being streamlined out of existence. Customer support is being replaced by chatbots trained on millions of conversations. Content production, once a haven for young graduates and freelancers, is being automated into template-driven text. Junior technical posts are being hollowed out as machines learn to test, debug and monitor systems faster than their human counterparts.

The most exposed job titles read like a directory of the modern middle class: admin, data entry clerk, typist, junior administrative assistant, scheduling or calendar coordinator, payroll processing clerk, records management officer; call centre agent, telemarketer, chat support executive, customer service representative; content writer producing generic search-engine copy, product description writer, social media caption writer; bookkeeping clerk, junior accountant; legal research assistant, claims processing officer; junior software tester, manual quality-assurance tester, basic web developer, IT helpdesk level one, system monitoring analyst; market research assistant, survey analyst, media monitoring executive, basic SEO analyst, advertising copy generator; and even creative roles now judged “safe” only in part — graphic designer producing simple layouts, video editor handling basic cuts, illustrator of stock-style images, and voice-over artist offering generic tones.

File Image |

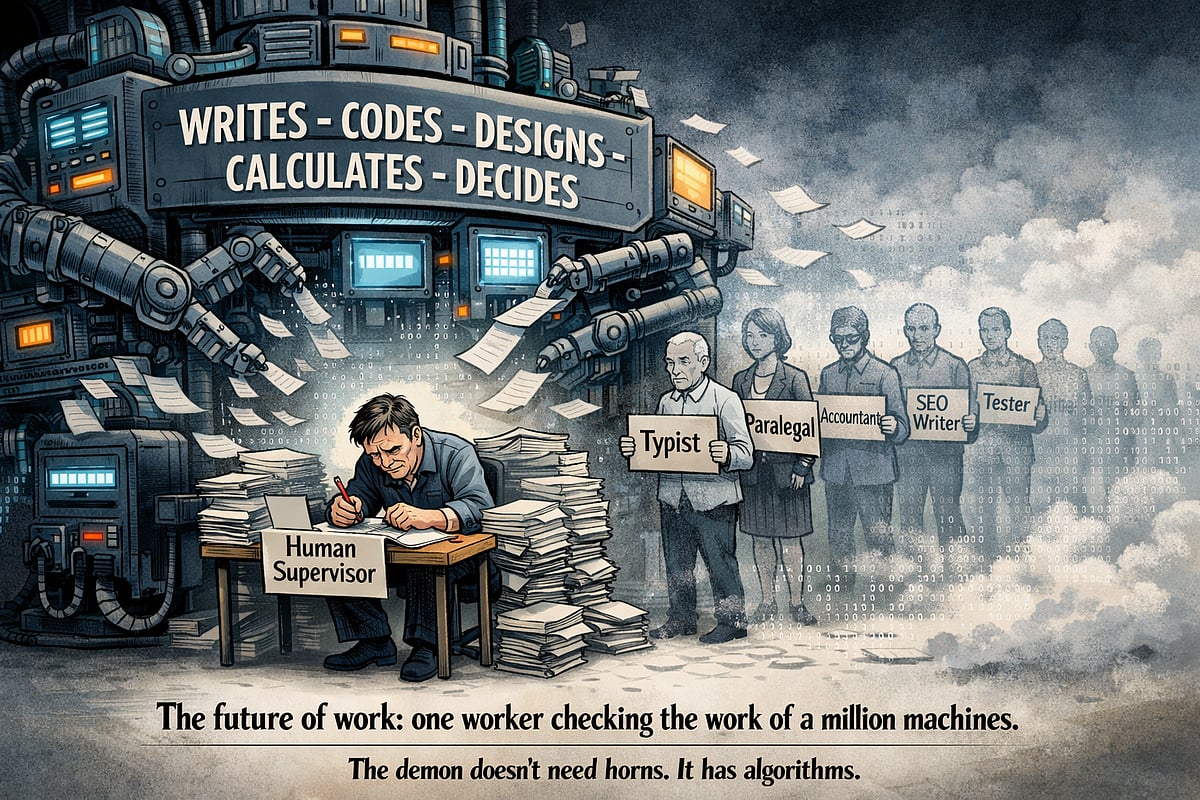

Artificial intelligence will not annihilate these professions overnight. Yet fewer workers will be required to do the same volume of work. The nature of employment itself is shifting. The “doer” is being replaced by the “checker”. The clerk becomes the supervisor of a machine. The graduate recruit becomes the editor of automated output. Hybrid roles — part human judgement, part algorithmic efficiency — are growing, but they demand higher skill at precisely the moment when entry-level opportunities are shrinking.

Recruitment data already carries the chill of bad news. Technology firms have slowed hiring markedly, and new postings have fallen sharply in recent months. The most vulnerable are those at the start of their careers, whose duties are easiest to codify. Over the next two years, many clerical, technical and sales positions may be automated or merged into leaner structures. For young workers, the ladder into professional life is losing its lower rungs.

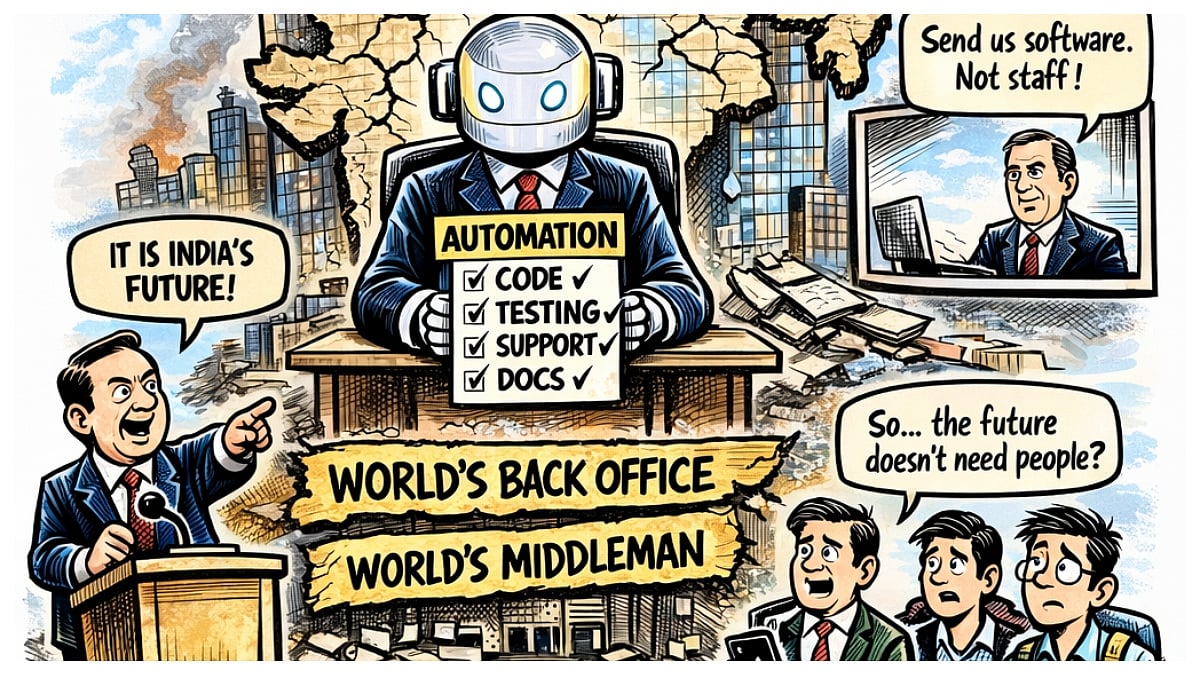

This unease is not confined to one country. On a global scale, the numbers are stark. Estimates suggest that around two-fifths of jobs worldwide will be altered, upgraded or eliminated by artificial intelligence, rising to well over half in advanced economies. Such figures conjure an image less of gradual reform than of a tidal wave. Labour markets are being reshaped faster than laws or training systems can adapt.

File Image |

For nations that built their prosperity on supplying skilled office labour, the danger is acute. Where once the export of IT services and business processing sustained millions of households, the new economy rewards the owners of algorithms rather than the operators of them. Structural weaknesses are exposed: insufficient investment in research, limited computing infrastructure, and an emphasis on service provision over invention. Even where citizens enthusiastically use foreign AI tools, their own economies may be reduced to customers rather than creators.

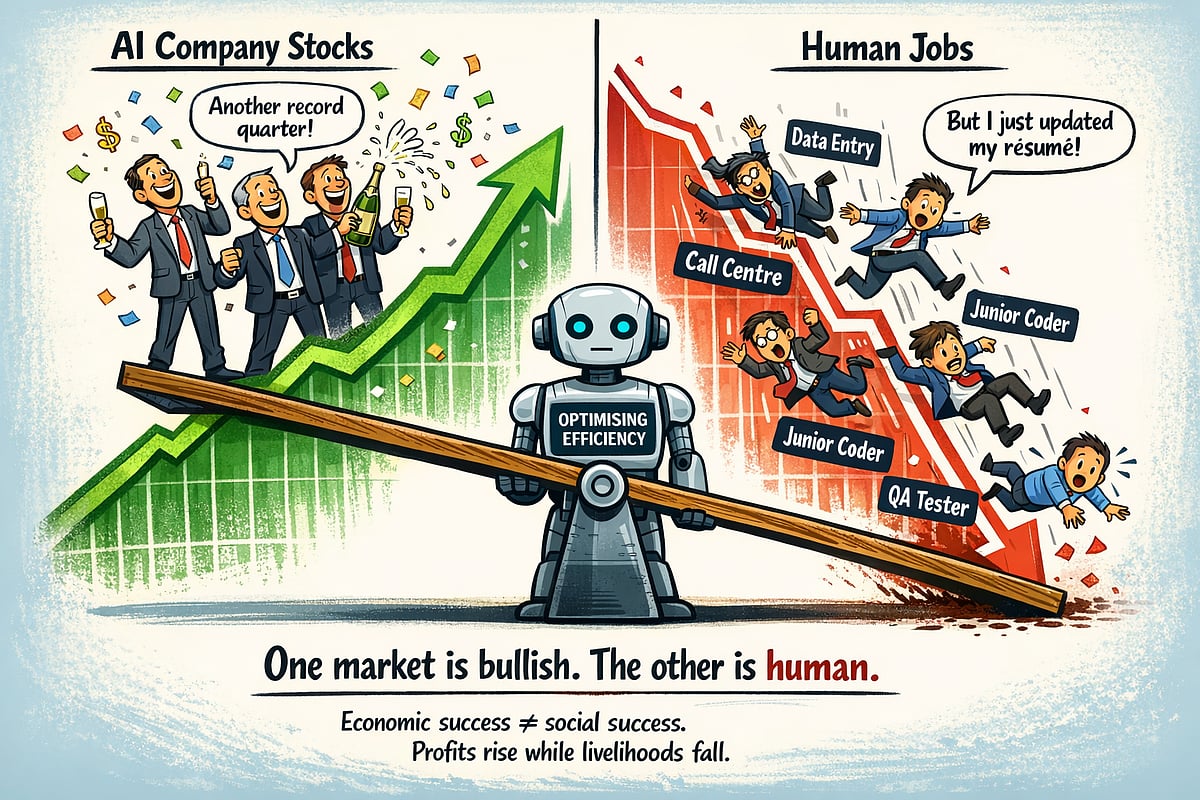

Financial markets have begun to register this anxiety. Share prices of established technology firms have wobbled as investors question whether traditional outsourcing models can survive in a world where software writes software. The contrast with global winners is unsettling. Profits and prestige are concentrating among a small group of foreign companies that control chips, platforms and advanced models. For domestic firms elsewhere, the fear is of disruption without compensation — a loss of relevance before reinvention is complete.

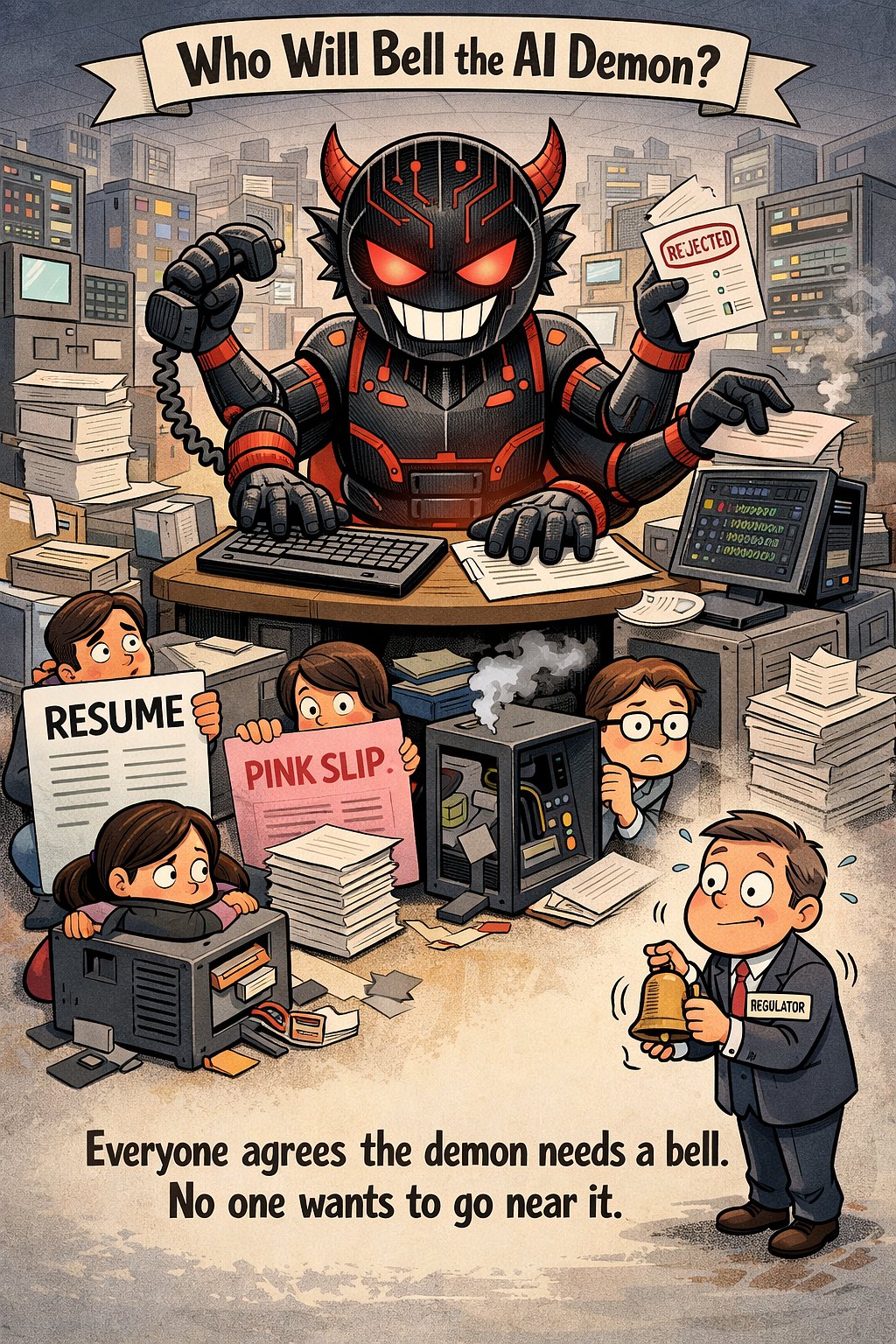

Regulators acknowledge that they are chasing a moving target. Trading systems now rely on algorithms; corporate decisions are guided by predictive models; entire workflows are automated from start to finish. Authorities speak of roadmaps and expert groups, but their language betrays a deeper worry: the pace of technological change outstrips the ability of rulebooks to keep order. Markets, like labour, are learning to live with decisions made at machine speed.

The human cost is already visible. Tens of thousands of workers have been laid off in start-ups and technology firms in recent months, with media and digital services suffering heavily. While companies promise to retrain staff for “AI integration” roles, such positions are fewer in number and higher in skill. For every engineer promoted to supervise a model, several clerks and support workers quietly disappear from payrolls.

Investors share the unease. Shares linked to traditional IT services remain under pressure as clients abroad reconsider contracts once thought secure. The old arithmetic of outsourcing — cheaper labour in exchange for stable demand — is being rewritten by software that knows no borders. Exposure to these firms, once a symbol of safe growth, now carries the scent of structural risk.

And yet, a note of guarded optimism persists. History teaches that technology can enrich as well as destroy. Economies with strong digital foundations, adaptable education systems and clear regulation may yet prosper. Artificial intelligence can enhance productivity, create new professions and unlock industries not yet imagined. But the lesson of the dotcom era remains stern: booms reward those who build the technology, not merely those who deploy it.

The present moment therefore resembles a fork in the road. One path leads to an economy of designers, engineers and ethical overseers, where machines amplify human judgement. The other leads to a hollowed middle class, where routine intellectual labour is stripped away and social tension grows. Which future prevails will depend on decisions taken now — in classrooms, boardrooms and ministries.

Artificial intelligence is not a distant storm on the horizon; it is already raining on the office floor. Its advance is quiet, bureaucratic and relentless. Spreadsheets are being replaced by models; helpdesks by chatbots; junior analysts by predictive systems. The danger lies not in a sudden collapse, but in a gradual erosion of opportunity, unnoticed until the ground has shifted too far to regain balance.

The dotcom crash taught the world that enthusiasm without preparation leads to ruin. Today’s AI boom carries a similar warning, but with higher stakes. It is not only capital that is at risk, but the livelihoods of millions whose work can be described, and therefore automated, in lines of code. Whether artificial intelligence becomes the engine of a new prosperity or the architect of a white-collar employment shock will depend on one question: will societies learn to build the machines, or will they remain content to serve them?