You have worn many hats through your career—engineer, investment banker, board-member for nonprofits and companies, philanthropist, leader. What was the moment or experience in any of these roles that really changed the way you think about philanthropy?

My wife and I started giving from the moment we got married. We weren't earning much at the time, we were living as paying guests, but we believed giving was a responsibility and so we started very early on.

But if I was to go back and look at inflection points, um, I would say there were two—the first was when I met Venkat Krishnan, founder of Give India. I realised that there are people out there like him who have basically dedicated their life to improving the conditions of people around them. That really struck me, that there is another way to use one's purpose.

The second inflection point came two decades ago when I read the autobiography of Chuck Feeney—The Billionaire Who Wasn't. That really blew my mind, that there were people out there who almost nobody had heard of, who had pretty much taken everything that they had created and given it back, almost anonymously, and in doing so, had impacted hundreds of millions of lives. That really made me and my wife Archana think about how we can live our lives differently.

Today, young professionals with only a fraction of industrialists’ wealth are becoming regular givers. Are young Indians beginning to look at social impact differently?

When we started giving, many people told us we should not be doing it, including some of my mentors who felt I should focus on the Hindu philosophy of ‘learning, earning and giving’, and defer this (philanthropy) to a point when I would retire. But I was very clear that I wanted to solve for the things that I cared about now, and not at a point of time in the future.

On the revival of the Indian giving movement, India has actually been the lighthouse for true giving—look at what the Tatas did a century ago, or the Godrejs. Somewhere along the line, I think we lost that. In a very odd way, our move towards socialism, which made us a scarce society, led people to care more about their own scarcity than that of others. By the 1990s, we were all very individualistic.

The last 20 years have therefore actually been energising because we are seeing the revival of the giving movement, led by different pockets, from first generation wealth creators and from some leaders like Mr Premji, Shiv Nadar, but also people like Ashish Dhawan and others.

Still, I would say it is still green shoots. Over the last two or three decades, wealth has grown enormously. We are approaching close to 2,000 families who have more than Rs 1,000 crore of wealth. But if you look at how many families give even Rs 5 crore, that number is less than 200.

What is the one subject you would dedicate your philanthropy to entirely?

In 2011-12, Marathwada was the epicenter of drought in Maharashtr, and it became the suicide capital of the country. To understand the issue a little bit better, I started travelling to Marathwada. We found a very interesting model—Caring Friends, run by Nimish Shah and Ramesh Kacholia, was rejuvenating water bodies in Jalna, a very unusual effort when everybody else was focusing on alleviation, loan waivers, etc. Nimish Bhai's point was to work with the community in a joint manner to solve the problem sustainably, by addressing the root cause, which was water.

We got involved in funding a series of other such interventions in Marathwada, and we saw firsthand how it could transform lives. Over a period of three-four years, a 100-plus water bodies were rejuvenated, impacting a few hundred villages. It was a very simple intervention, it didn't require a big multi-year project. It required working with the community.

In partnership with the Maharashtra government now, we have worked on over 10,000 water bodies, impacting about 15,000 villages. We now work in 11 states on water.

Our journey with water just tells you sometimes you have to ask the deeper question as to why something is happening and how I can eliminate it, as opposed to putting someone on this treadmill of charity.

How is technology changing philanthropy, but also, is its promise limited until access to technology is truly democratised?

Yes, we will have to democratise access. Today, rural penetration is about 70%, and we'll have to up that number to ensure no one is left behind when we are trying to push social solutioning.

But five years from now, there will be two kinds of organisations and individuals—those who embrace technology and those who don't. Those who embrace technology will drive deep impact, and those who do not will risk becoming completely redundant. The adoption rates will surprise all of us. The most underserved segments, like agriculture, will start seeing deep embracing of technology at a rapid pace over the next two to three years. It will start changing agriculture as we know it today. I've already started seeing it in education, even at anganwadi levels.

I personally feel that 60%-70% of NGOs will become irrelevant. They will exist, but they will basically be largely irrelevant, because they will not know how to react to these technology changes.

What would you say today to young people who want to join the philanthropy space?

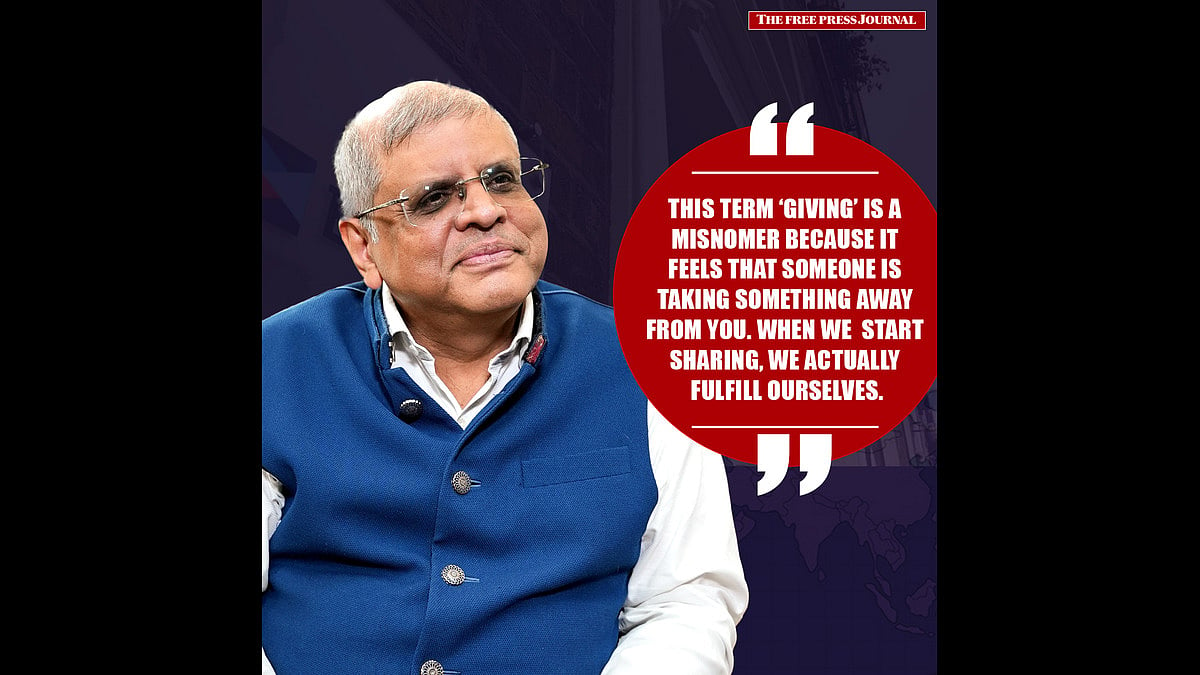

In general, I would say, this term ‘giving’ is a misnomer because it feels that someone is taking something away from you. It’s important early on in our lives to realise that this is as much about getting as it is about giving, because when we actually start sharing, whether it's our skills or a little bit of our money, what we do is we build our perspective, we fulfil ourselves. So the earlier we start doing that, the better it is.

As time goes by, you see that life is a lot more than just your bank balance.