The parliamentary debate marking the 150th anniversary of ‘Vande Mataram’ has revived an 88-year-old controversy, casting the Congress into a quandary (as the BJP doubtless intended). The grand old party can either stand by the 1937 and 1950 decisions to truncate the song and keep it out of the constitutional ambit or revisit the issue in light of the shift in Indian sensibilities and political culture.

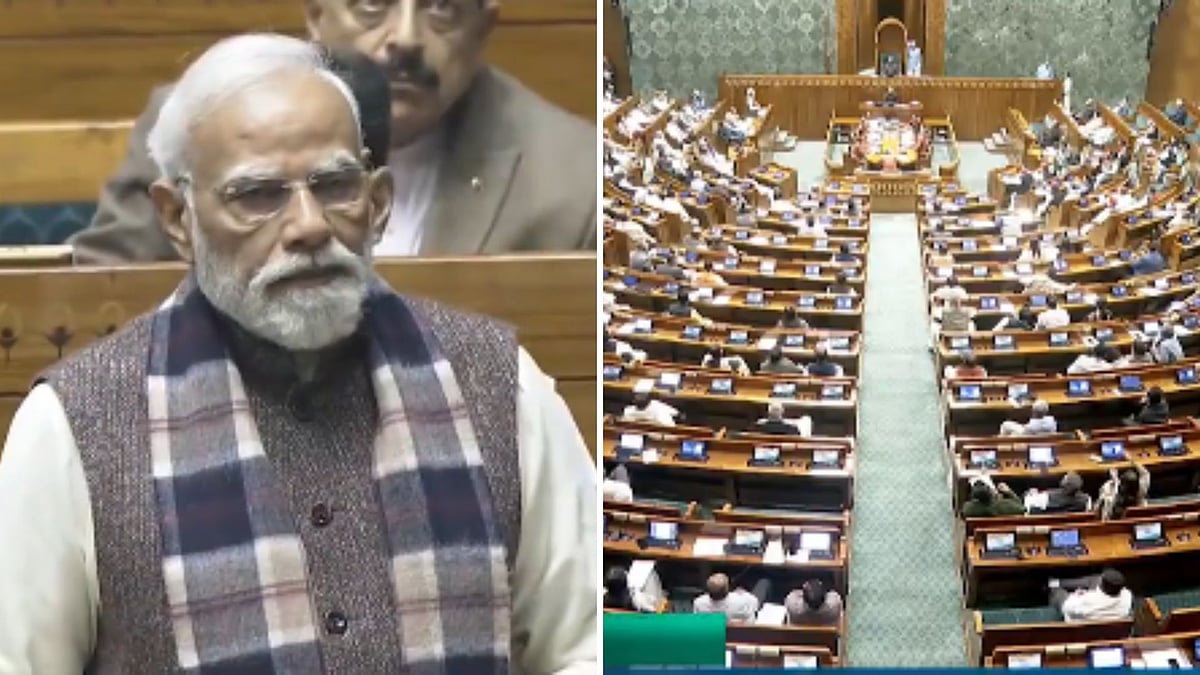

For PM Modi, his championing of Vande Mataram, ‘I bow to you, Mother’, is part of what he dubbed the “psychological renaissance” of India, a shedding of the colonial mindset and reclamation of its civilisational heritage. For Congress general secretary Priyanka Gandhi Vadra, questioning the status of the song amounts to an attack on her great-grandfather, Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru. Both approaches are subjective, but neither is disingenuous.

Bankim Chandra Chatterjee’s cri de coeur, which became the anthem of the world’s largest mass movement, enjoys a high emotional quotient. It inspired millions and was the rallying cry of the anti-Partition protest in 1905. Banned by the British Raj as seditious, it became a cause célèbre for students of the Hyderabad state in 1938. Many a martyr died with the song on their lips. On the eve of Independence, Sucheta Kriplani commemorated their sacrifice by singing the first stanza of the song. Given its intimate association with the freedom struggle, the fading out of Vande Mataram is distressing.

So, Modi was expressing a national sensibility when he advocated restoring the anthem of the freedom struggle to its original form and pre-eminent status. He pointed out that, as a cultural expression, Vande Mataram represents a shared legacy that was above political divisions. But Priyanka Gandhi characterised the BJP’s motives in debating the issue as strategic rather than patriotic.

That Vande Mataram no longer figures prominently in public consciousness is a fact. Technically, it enjoys equal status with the national anthem, but the Constitution recognises only the latter. The Supreme Court, in a 2017 ruling, dismissed a petition demanding that Vande Mataram be accorded equal status with the national anthem under the Prevention of Insults to National Honour Act, 1971.

Far too few of us remember Vande Mataram, simply because it’s not compulsory in schools and, therefore, heard a lot less often. Ask school students to rattle off the national anthem, and they launch into “Jana Gana Mana” with verve. We grow up with the national anthem, singing along wherever it is played in schools, cinemas, and public functions, revelling in the feeling of pride and communion that it inspires. In a way, the primacy of Tagore’s Jana Gana Mana over Vande Mataram represents the triumph of the Nehruvian consensus.

The assertion that Vande Mataram was truncated in 1937 to accommodate Muslim sensibilities is generally accepted, with the caveat that the political exigencies of the time demanded a nuanced approach. Only the first two stanzas were deemed acceptable, as the Muslim community might object to the “idolatrous” religious references in the subsequent part of the song. Durga, Lakshmi, and Saraswati were strategically left out, in deference to the need for a united opposition to the British rule.

The same logic, that it might wound the Muslims, was applied in 1950. Many voices in the Constituent Assembly, notably that of Seth Govind Das, preferred Vande Mataram over Jana Gana Mana. But it was a time when Nehruvian ideals, notably secularism and democratic socialism, held sway over all other discourses. Nehru’s personality cult and public faith in his leadership carried the day.

The Rashtriya Swayamsewak Sangh (which was not associated with the Constituent Assembly) has always celebrated ‘Vande Mataram’. It is sung in shakhas and at public events in its original form. Officially, both the national anthem and the national song are accorded equal respect by the RSS; Jana Gana Mana is regarded as the emblem of the state (rajya) and Vande Mataram as that of the nation (rashtra).

That the debate over Vande Mataram should be revisited three generations later is inevitable. As political and cultural consciousness shifts, the past is re-examined and the role of historical characters re-evaluated. Today, Nehru’s domestic and foreign policies have become a subject of criticism and are approached from perspectives informed by a muscular nationalism. Critiquing Panchsheel has become fodder not just for right-wing authors but for laypersons. Priyanka Gandhi’s angst is understandable, and her solution to the endless sniping about Nehru and dynasty is commonsensical. Let’s have it out once and for all, she said, and then let it go.

She alleged that Vande Mataram was being leveraged for the upcoming West Bengal assembly elections and to distract voters from economic hardships. Whatever the motive, Vande Mataram is certainly an emotional issue in West Bengal, the cradle of Indian nationalism, and all parties will now have to integrate it into their electoral campaigns. State Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee welcomed the debate on Vande Mataram but sought to checkmate Modi by objecting to his use of the wrong honourific for Bankim Chandra Chatterjee.

Banerjee finds herself a bit on the back foot, with the poet’s great-grandson criticising the West Bengal government for neglecting his legacy. While Tagore’s ‘Banglar Mati, Banglar Jol’ has been made compulsory alongside Jana Mana Gana, Vande Mataram has not found a place in West Bengal schools. In a deft move, Uttar Pradesh CM Yogi Adityanath has declared that it will be mandatory in schools in his state.

Meanwhile, Rajya Sabha MP Sudha Murty made an impassioned plea to introduce the song in schools across the country, lest children “lose the entire text of Vande Mataram”. If the suggestion gains traction, the Congress will have to decide whether to embrace all of the song or only a part of it.

Bhavdeep Kang is a senior journalist with 35 years of experience working with major newspapers and magazines. She is now an independent writer and author.