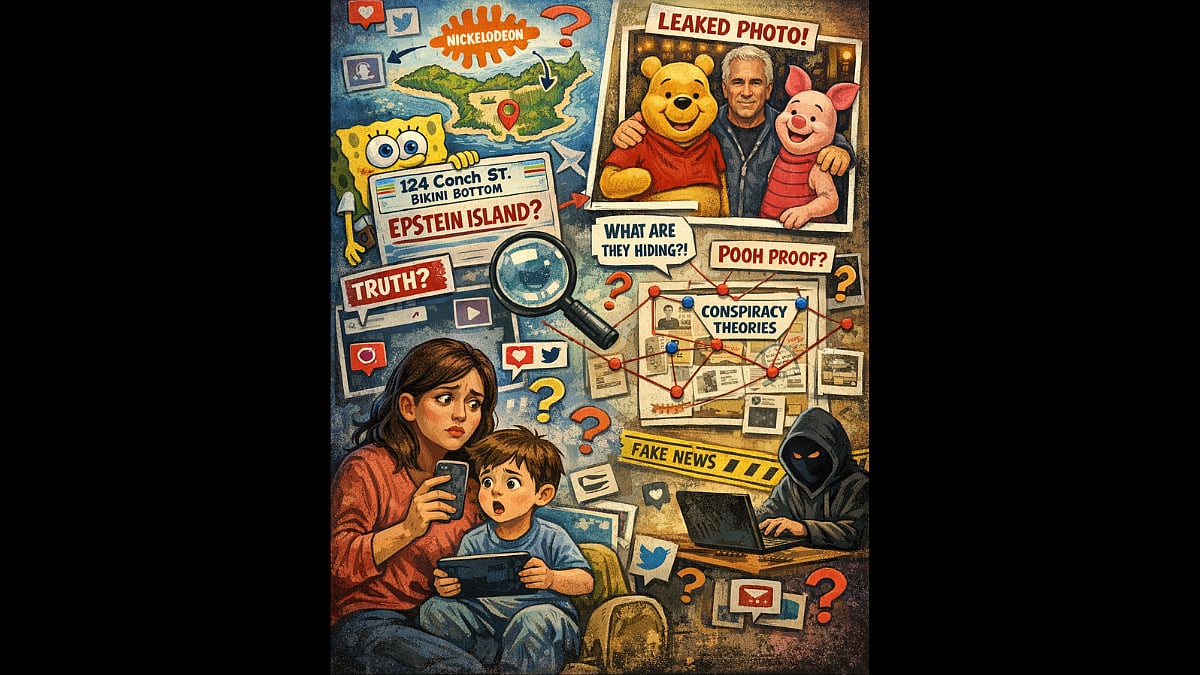

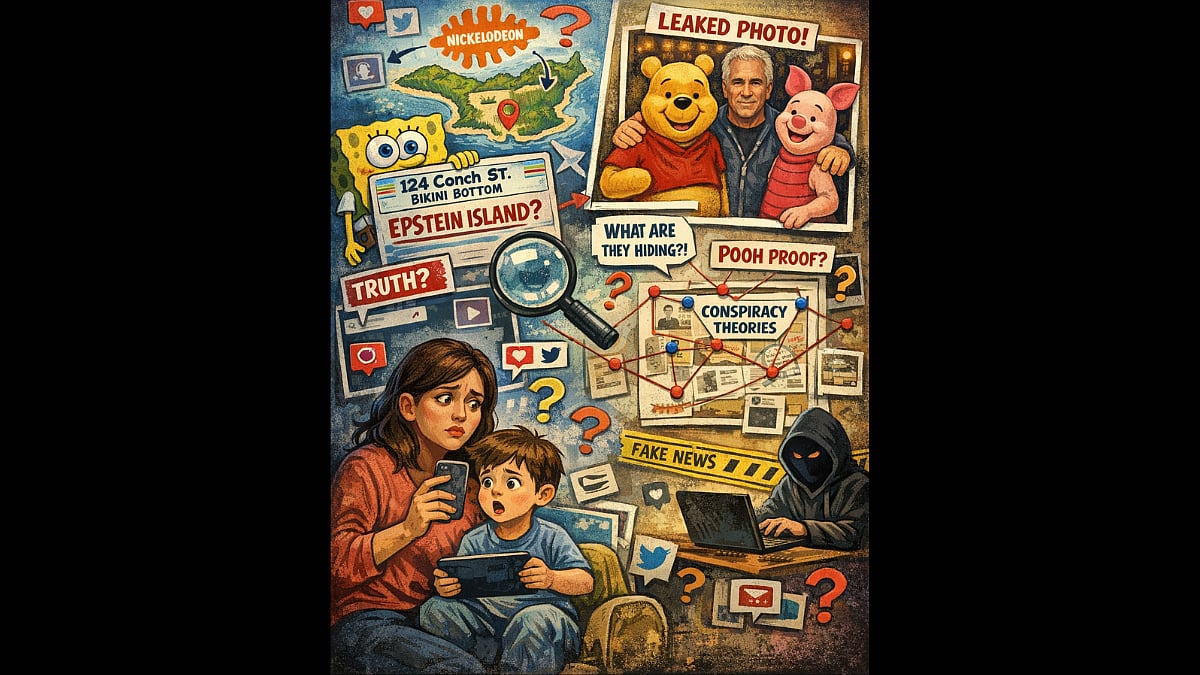

In the winter of 2025–26, a head-scratching moment gripped parts of the internet: what did a cartoon sea sponge and a honey-loving bear have to do with Jeffrey Epstein, the disgraced financier and convicted sex offender whose name remains synonymous with one of the most notorious criminal networks in recent memory?

The short answer is, nothing. Yet for a few weeks, social media feeds around the world filled with posts, memes, videos and threads, all claiming, hinting or outright asserting that the colourful worlds of SpongeBob SquarePants and Winnie the Pooh carried sinister connotations tied to Epstein’s crimes.

Shape of the Island

The first meme-worthy connection surfaced not in court documents but on a screenshot, someone saying the fictional home address shown on SpongeBob’s driver’s licence — “124 Conch Street, Bikini Bottom” — had appeared in a Google Maps search allegedly tied to Epstein’s Little Saint James island. The claim spread like wildfire, amplified by forums such as the /conspiracy sub-Reddit, framed as “proof” of a hidden link between the Nickelodeon character and Epstein’s private domain. Some, such as X user @MarcTheMesenger, even said that the shape of the island was the same as that of the Nickelodeon logo.

Fact-checkers debunked this, showing that the “map” result was an artefact of user-generated prank listings and spoof entries that had nothing to do with Nickelodeon or the show’s creators. There’s no evidence that SpongeBob or Nickelodeon have any explicit connection to Epstein’s life, properties or crimes.

But by then, the story had already metastasised across online platforms. In one of the more vocal and viral Reels, Instagrammer @jumperspodcast alleged that SpongeBob was actually created to entertain the children on “Epstein Island”, and repeated the address theory.

Reactions and reposts set the internet ablaze, and then came a controversy around another cartoon character.

Bah to the Pooh?

In the release of thousands of legal documents and images linked to Epstein’s investigations under new transparency laws, among photos of real people and locations, a couple of snapshots went viral, showing Epstein standing alongside performers dressed as Winnie the Pooh and Piglet at Walt Disney World’s Crystal Palace restaurant.

These photos aren’t hidden evidence of wrongdoing or criminal fraternization, but vacation snaps presumably taken when Pooh, Piglet and other mascots pose for photos with guests. Disney has not said anything to suggest the images imply misconduct.

Yet the juxtaposition of a universally cherished children’s icon with one of the most reviled figures in recent history was enough to set off an emotional cascade online. People tweeted heartbreak emojis; others joked about Pooh’s “identity” being redacted; some insisted the photos were a sign of larger conspiracies.

Memes and mistrust

Into the already murky waters, memes made a new splash. A familiar pattern in meme culture is to latch on to unexpected juxtapositions, turning them into viral currency regardless of context.

Seema Ghosalkar, mother of a seven-year-old who loves watching cartoons, says she was startled when she saw the Instagram reels about SpongeBob. “For a moment I panicked. Was my boy being subconsciously indoctrinated?” She talked to her friends who have similar-aged children, and they agreed to “block” the cartoons, telling their kids that there was something wrong with the cartoon programming for a day or two, until they could decide what to do.

“I went over as many SpongeBob episodes as I could, almost obsessively, all the while hiding it from my son,” says Ghosalkar, laughing at the memory. “I even hid in the toilet once. My earbuds were always in.”

She and other parents realised soon enough that their children were not watching something dangerous. “I didn’t find anything wrong in the cartoons,” says Ghosalkar.

Her friend Preeti Mehta, mother of an eight-year-old girl, agrees: “I always tell my friends not to believe Insta reels and online trends until we can verify them. People do anything for content!”

Don’t worry, say experts

Experts and child psychologists say the same thing that fact-checkers have — there is no credible evidence that these cartoons contain embedded references, symbols, or messaging tied to Epstein’s crimes. They remain fictional worlds created for entertainment, not coded vehicles for harmful ideology or grooming.

Child psychiatrist Dr Rashmi Gada says the one beneficial fallout of the controversy is that parents are likely to be more careful about what content their children consume, on TV and online. “Some cartoons have undesirable subtext,” she says. “A popular pig character, for instance, is criticised for encouraging rude and entitled behaviour. But it all comes down to the level of parental engagement in their children’s lives as a whole. If the parent knows what their child is reading and watching, and is there to answer questions the child may have, it will go a long way to help.”

In general, children’s programming has long been examined for the kinds of values, humour and behaviour it portrays, though most studies focus on short-term attention, not on possible embedded conspiracies.

Dr Gada adds, “Children imitate caregiving adults, not memes or online tricks. The real influence on a child’s worldview comes from what adults guide them to notice, question and reflect on.”

Storm in the memecup

In the end, the SpongeBob-Pooh-Epstein drama was never a scandal in the legal or journalistic sense, but a meme-driven trip through the often-confusing landscape of today’s digital culture. For parents, the takeaway is simple: don’t panic, and don’t over-interpret bizarre internet claims. Your children’s cartoons are just that — cartoons. What deserves parents’ attention isn’t a spongy sea creature’s fictional address or a bear’s theme-park snapshot beside a disgraced adult, but the real issues of safety, empathy and critical thinking that these viral moments inadvertently highlight.