When crowds head to Dadar’s Chaityabhoomi for the December 6 rally on Dr BR Ambedkar’s death anniversary every year, the common complaint is how “these people” take over practically every available space. Public transport, common areas, every nook and corner is occupied by the “Jai Bhim waale”. It is a cause for complaint among Mumbai residents as well as commuters, who are resigned to grit their teeth for these few days.

“If we are not vigilant, they enter our building and sleep overnight in the corridors,” says Mitali Patankar, a resident of Shivaji Park. She goes on to explain that it is not a bad thing by itself, “but they leave no space for us residents to move”.

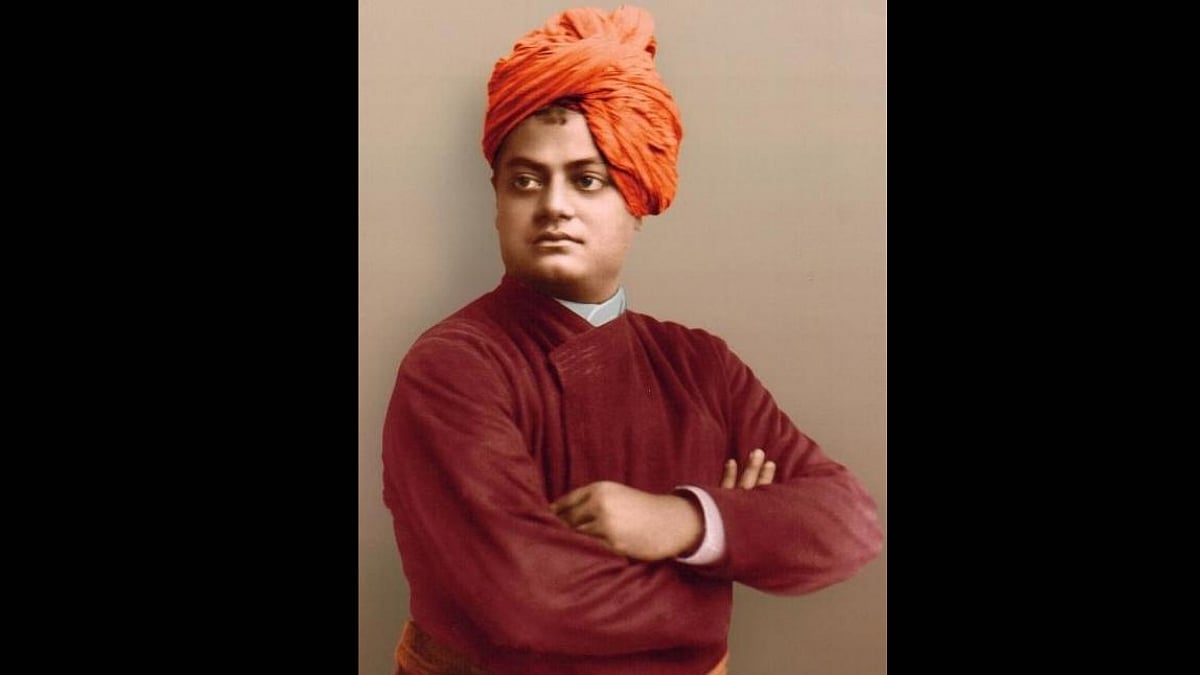

People pour in a day or two earlier from all over the state, to honour the memory of one of the greatest reformers of society. More than the acknowledged architect of the Constitution, Dr Ambedkar was a revolutionary thinker who paved the way for modern life as we know it.

Sociology lecturer Kiran Vengurlekar explains: “People love to box Ambedkar into ‘oh, he only gave reservations’ or ‘only helped SC/ST’ but that’s a lazy half truth. The reality? His impact is everywhere around us, even if people don’t connect the dots. Our Fundamental Rights like freedom of speech, equality before law and protection from exploitation? That’s Ambedkar’s Constitution at work. The reason you can even criticise him openly on social media without fearing jail is because he made sure those rights were enshrined.”

The eight-hour workday, Vengurlekar says, came about because of Dr Ambedkar’s fight through the Factories Act of 1948, where he pushed for humane working conditions, rest periods and fair hours. “He was one of the earliest voices for workers’ dignity,” he says.

Even the Reserve Bank of India was built on the ideas in his doctoral thesis; the literal backbone of India’s financial system owes him credit, points out Vengurlekar.

But these facts are almost obscured by the noise around the question of caste, chiefly because of Dr Ambedkar’s seminal work, The Annihilation of Caste. The first thing that most youngsters say on hearing his name is “reservations”.

Rashmi Vora, a political science post-graduate student, says, “I understand why it exists, and I know it’s still needed to address the systemic barriers and generational exclusion that Dalits, Adivasis, and OBCs have faced. But I also believe that reservation by itself is not enough. What’s missing is a simultaneous push for social reform, mass awareness, and education that questions caste. We have reservation policies on paper, but we’ve failed to build the cultural shift needed to dismantle caste consciousness. We don’t teach caste history properly. We don’t run campaigns to reduce caste-based prejudices.”

And these prejudices then translates into the “us vs them” that always surfaces around December 6 and April 14.

This reaction only underlines the social divide which ironically Dr Ambedkar sought to eradicate. To many young Indians, especially those from marginalised communities, Dr Ambedkar represents the possibility of self-making through education, law, and intellectual rebellion. Ambedkar statues dominate the landscapes of Dalit neighbourhoods, not as decorations but as public declarations of dignity in places where dignity is constantly contested.

Ninad Naik, who studied Economics but plans to pursue a doctorate on Dr Ambedkar, says this trend is disturbing. “I’ve noticed a growing trend among his followers where they’re elevating him to a divine status, almost like a god. Ambedkar himself fought against the very concept of blind worship and idolisation, yet his followers are replacing one form of fanaticism with another. I deeply respect him for his fight for justice, equality, and human rights. But it’s disheartening to see his legacy being turned into a cult of worship. Let’s honour his teachings and stay true to the principles he stood for — equality, justice and freedom, not the worship of a human being.”

“Reservation without reform becomes a Band-aid over a festering wound,” says Vora. “It gives access, but not always support. It creates seats, but not always respect.”

Women hating on him shows a lack of understanding, she adds. “Without Ambedkar, the fight for women’s equality in India would have been much longer and harder. His work on the Hindu Code Bill and women’s education made him one of the strongest feminist voices of his time.”

To understand India today — its aspirations, its unfinished struggles, and its ideological fracturing — one must revisit Ambedkar not as a statue or icon, but as a restless, insurgent mind who refused to bow to the status quo.

Vora quotes from an essay she submitted at her institute: “A democracy cannot survive on rituals, elections, and patriotic slogans alone. It must confront the inequalities buried within its own culture.”

Coming from a Gen Zian, perhaps this holds out hope for the generation to come.