With the path to the Mayorship now clear, Mumbai is set to appoint BJP corporator Ritu Tawde as its new Mayor this Wednesday. While the election is officially scheduled for 12 pm at the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation (BMC) headquarters in Fort, the proceedings are expected to be a mere formality, as no opposition party has fielded a competing candidate.

Once Tawde takes the helm, what actual power and privilege does the office hold? As the "First Citizen" of India’s financial capital, the Mayor of Mumbai occupies a role steeped in historical prestige and significant civic influence.

Clad in traditional robes and accompanied by a silver mace during house proceedings, the Mayor enjoys high-profile perks including a sprawling heritage bungalow and a red-beacon vehicle.

However, this outward display of authority masks a 138-year-old structural paradox. While the office commands immense public respect, it lacks the legislative teeth to drive the city’s vast administrative machinery.

Under the current framework, the Mayor remains a titular head whose primary function is to preside over civic meetings, leaving them as a ceremonial figurehead in a city that demands aggressive executive action.

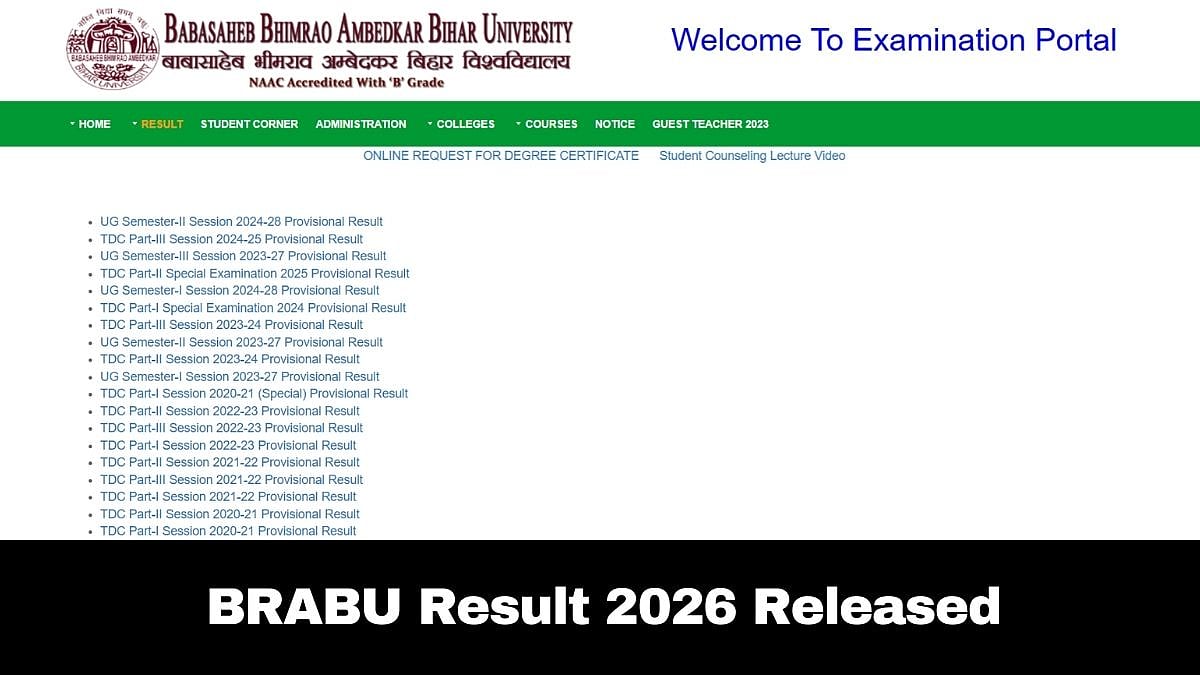

Legislative blueprint of the 1888 BMC Act

This lopsided power dynamic is not a result of modern political manoeuvering, but a legacy of British colonial administration enshrined in the Mumbai Municipal Corporation (MMC) Act of 1888.

Originally designed to ensure that crown-appointed officers retained control over finances while allowing local representatives a deliberative voice, the Act continues to serve as the city's governing "constitution."

Specifically, Section 4 of the Act designates the Municipal Commissioner—an IAS officer appointed by the state—as the sole authority vested with executive power. Because the law does not grant the Mayor "power of the pen" over the municipal fund or the ability to sign off on projects, they are legally sidelined from the city's day-to-day governance.

The Rs10 crore barrier

The true centre of gravity within the BMC lies in this executive wing. This power imbalance is most evident in financial clearances. While a Mayor might champion a grand vision for infrastructure, they cannot unilaterally authorise even a Rs10 crore project without the Commissioner’s nod.

Every significant contract and policy shift requires the Commissioner’s signature. This creates a recurring tension where the people's elected representative must effectively lobby a state-appointed bureaucrat to fulfill campaign promises, rendering the Mayor effectively powerless when faced with the cold reality of the municipal treasury.

Bridging the gap

With a BJP mayor now dealing with a city governed by a state-appointed administrator introduces a unique solution through the "Double Engine" governance model.

Historically, conflict arises when the state government and the BMC are controlled by opposing parties, leading to deadlocks between the Mayor’s office and the Commissioner.

As the BJP holds power at both the state and city levels, the traditional wall between the elective and executive wings may begin to thin. In this scenario, the Commissioner—who answers directly to the state—is more likely to act in lockstep with the Mayor’s agenda, effectively bridging the 138-year power gap through political alignment rather than legislative reform.