Donald Trump’s second thoughts about the two new laws regarding restive Hongkong that he signed recently confirm that US anxieties are not at all about the pro-democracy movement in the former British colony. His fear that with a new round of tariffs due to be announced on December 15, the two measures could complicate any trade deal with China confirms that the real worry is commercial.

One of Mr Trump’s two measures authorises the US to sanction Chinese officials over human rights abuses in Hongkong. The other, the Protect Hongkong Act, prohibits US companies from exporting non-lethal crowd-control munitions, including tear gas and rubber bullets, to the city authorities amid allegations of disproportionate force by the local police during the six months of protest culminating in elections in which pro-democracy candidates captured 17 out of Hongkong’s 18 district councils. Democracy in Hongkong can expect more than lip service only if the cause also serves someone else’s interest. That factor ensured Indian support for East Bengal in 1971. The coalescence is unlikely to be repeated.

The Sino-US trade war matters more to Mr Trump than human rights in Hongkong. But Washington can camouflage its real interest. Tibet is a case in point. Despite fulminations about human rights there, the US has done precious little to compel Beijing to introduce reforms, allow exiled Tibetans to return, or restore the Dalai Lama’s authority. Every so often an American president stages an “accidental” meeting with the Dalai Lama to remind China he still has an ace of spades up his sleeve. But he doesn’t play the card for that would use up all its bargaining value.

The last meeting between the Dalai Lama and a US president (Barack Obama) was in 2016 and coincided with Japanese and American accusations that China was extending its influence into the Western Pacific with submarines and surface vessels and pushing territorial claims in the South China Sea. In one incident of brinkmanship, a Chinese observation ship shadowed a US aircraft carrier as it joined Indian and Japanese warships for drills (the famous Quad) close to waters Beijing considers its backyard. China’s official news agency accused Washington of breaking its promise not to support Tibet’s independence: the US had “seriously jeopardized China-US relations, and deeply hurt the Chinese people’s feelings.”

The current Sino-US crisis peaked in November when the US administration jacked up import tariffs on US$ 200 billion of Chinese goods to 25 per cent, and threatened equal tariffs on another US$ 340 billion, presenting the Chinese government with a serious problem. Beijing retaliated by slapping 25 per cent tariffs on US$60 billion of imports from the US. But can this kind of tit for tat go on forever, with the threat of sending the prices of all commodities through the roof? Last year, US imports from China were valued at US$ 540 billion while China’s imports from the US stood at a mere US$ 155 billion or, perhaps, a slightly higher US$ 180 billion, if all the American merchandise shipped to Hongkong is included.

So, if the US imposes 25 per cent tariffs on everything it buys from China, and China retaliates by doing the same, its retaliation will be quite mild in comparison. Moreover, many US imports - advanced semiconductors for example - are important for China’s economic development. Making them expensive will have a damaging effect on Chinese industry. Trying to reduce the impact through subsidies to injured importers would defeat the object of imposing tariffs - which is to reduce sales to hurt the exporting economy - in the first place.

It has been suggested that China can also hurt the US by getting rid of its declared holdings of US Treasuries. This sounds like a viable threat since these holdings are valued at a colossal US$ 1.1 trillion. US bond prices would at once collapse if Beijing sold them, which would mean a sharp spike in US interest rates. The argument is that such a public sale would punish the American economy by destroying global confidence in the US dollar. But although US$ 1.1 trillion sounds a huge fortune, it’s actually less than 5 per cent of the total outstanding. If Beijing sold the bonds slowly, private investors would have little difficulty absorbing them, especially given the safe haven flows into the Treasury market at a time of heightened tension.

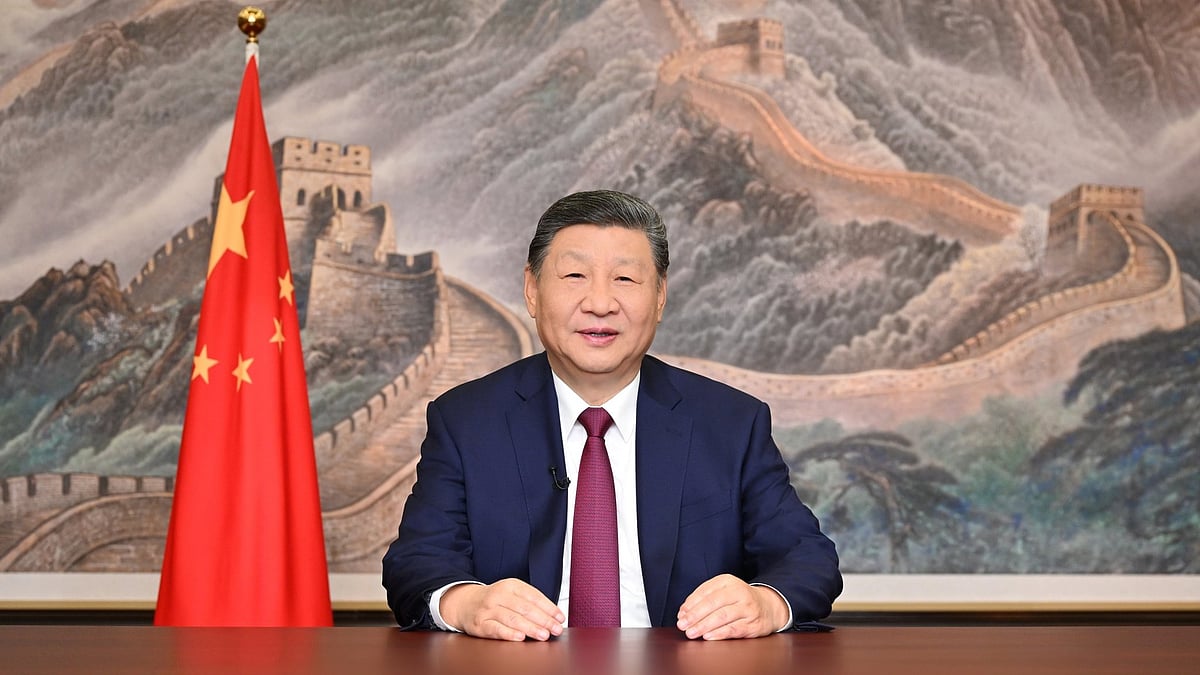

If China were to try and sell them all at once, the US Federal Reserve would step in and buy them to preserve an orderly market and hold down interest rates. It did just that - buying even more - in the course of a few weeks in 2008 when Lehman Brothers, with more than US$ 600 billion in assets, filed for bankruptcy. Even if the Chinese did succeed in selling their US Treasury bonds, it would be impossible to find an alternative investment. The euro market is saturated. Moreover, selling US dollars would push down the dollar’s exchange rate, benefiting US exporters and further hurting Chinese companies already penalised by US tariffs. What Mr Trump wants is that China should return to the 150-page outline trade deal which it rejected so effectively not long ago. That would imply a setback for Xi Jinping’s long-term goal of yuan internationalisation, loss of face, and public acceptance of constraints on Beijing’s industrial strategy.

The US knows that sanctions are a two-way street. The Institute for International Economics in Washington calculated in 1995 that sanctions cost the US economy $ 20 billion in lost exports, and 200,000 Americans their jobs. That’s why Washington found a way round the sanctions it imposed on India and Pakistan in 1998. America’s wheat-growing northwest states feared another glut and a slump in world prices if they could not sell to Pakistan which had bought 37 per cent of the wheat grown in that region the previous year. Pakistan faced another food shortage but sanctions prevented a similar deal.

Hefty Chinese tariffs have already seen US soybean sales to China fall by 90 per cent to be replaced by imports from Brazil which expects a crop 27 per cent bigger than the US this year. China bought more than 13 billion pounds of Argentinian beans this year, out of its total demand of roughly 187 billion pounds. In October, almost 100 per cent of Argentina’s soybean exports went to China. Expecting a bumper crop in 2020, Argentinian farmers hope that efforts to clinch a China-US deal will be frustrated.

That’s what the quarrel is all about. Mr Trump gives two hoots for democracy and human rights in Hongkong or any other foreign territory if US profits are not affected. That’s why New Delhi could rely on his acquiescence in Jammu and Kashmir.

The writer is the author of several books and a regular media columnist.