Mumbai, Jan 22: It was in March 1995. I was with Balasaheb Thackeray in his bungalow “Matoshree” in Bandra (East) when his personal assistant gently reminded him that he had to go to Mantralaya. Balasaheb told me that Manohar Joshi, the chief minister handpicked by him after the massive victory of the Shiv Sena–BJP alliance in the Assembly polls, was going to take charge of his office in Mantralaya and asked if I would like to accompany him.

I readily agreed and travelled under heavy police escort to Mantralaya. The CM’s office was on the sixth floor. Balasaheb got into the elevator, followed by his burly, black safari-clad bodyguards. The elevator was chock-a-block, and I could not squeeze in. But I was determined to witness the historic event of Maharashtra’s first non-Congress CM assuming office.

I ran up the stairs to the sixth floor like a man possessed and managed to reach the CM’s office just as Balasaheb was stepping into the big cabin after accepting the greetings of countless Shiv Sainiks and government staff.

Refusal to sit on the seat of power

Clad in a bandhgala suit, Manohar Joshi stood up reverentially, touched the Sena leader’s feet and requested him to sit on the CM’s chair. Balasaheb adjusted his off-white shawl, looked straight into Joshi’s eyes, touched him on the shoulder and told him in Marathi, “I have given you this chair to work for the welfare of the people of Maharashtra. It is not for me to sit in it.”

Imagine a politician actually refusing to occupy the seat of power. But then, that is Balasaheb for you.

Ideology before power

A cartoonist by profession—he was with The Free Press Journal in the early sixties—Balasaheb founded the militant Shiv Sena in June 1966 to work for the welfare of the Marathi “manoos”. The party came to power almost three decades later. The Sena could have captured power in the state much earlier had Balasaheb compromised on his ideology, but he stubbornly refused to do so.

This was his second quality, again something unusual for politicians. He did not believe in power at any cost.

The Sena captured power in the cash-rich Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation (BMC) and retained it for a full 25 years.

Alliance with BJP

The Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) was disappointed that it was not able to grow politically in the capital of the nation’s most industrialised state. It realised that the Sena, with its slew of shakhas and vast organisational base, was a power to reckon with in Mumbai. Its leader, the late Pramod Mahajan, found a kindred soul in Balasaheb, and they formed an alliance with Hindutva as its leitmotif.

Simultaneously, the Shiv Sena decided to spread its wings across the rest of Maharashtra. Balasaheb handpicked second-rung leaders and dispatched them to different parts of the state to plant the saffron flag of the party. For example, Diwakar Raote, a hardcore Sainik, was asked to open shakhas in Marathwada, and he did a commendable job of the task assigned to him.

Aversion to caste politics

The third noteworthy quality of Balasaheb was his aversion to casteist politics—again something unusual in an Indian politician. “One should only cast his vote and not vote his caste,” he used to say. He himself belonged to the CKP caste but never promoted it in his party.

Militant politics and mass appeal

The violent politics practised by him attracted the youth in a big way. When the Sena found that South Indians were employed in large numbers in nationalised banks, insurance companies and other PSUs, he launched the Sthaniya Lok Adhikar Samiti and, through it, got lakhs of jobs for the Marathi “manoos”, which won him the loyalty of the middle class.

Before that, he ran a virulent campaign against the communists, who had a firm grip over textile mill workers and those employed in engineering industries in the suburbs. Balasaheb floated the Kamgar Sena and, through violent tactics, eliminated the Reds from all these unions.

His critics alleged that he did this at the behest of a powerful cabal of industrialists worried about the growing clout of the communists. Balasaheb couldn’t care less. He said his task was to get jobs for Marathi youths.

Post the violent anti-Babri protests, he ordered Shiv Sainiks to hit back at Muslim rioters “to ensure the safety of Hindus”. These riots of the early ’90s majorly helped the Shiv Sena, and it performed very well in the 1995 Assembly elections.

Cult figure and political dominance

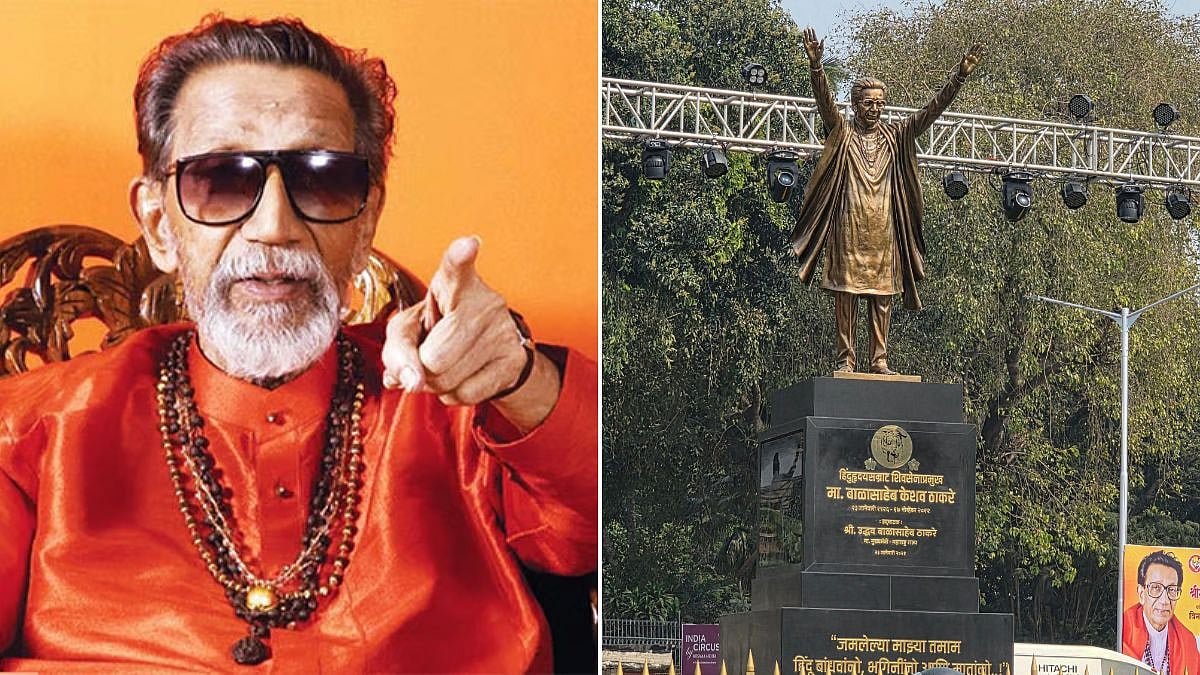

Over a period, Balasaheb acquired cult status and became a powerful political icon of Maharashtra—admired by many and feared by many more. In tandem with the BJP, he pushed the Congress to the corner and occupied the political space vacated by the grand old party.

Many accused Balasaheb of behaving like Hitler, whom he admired unapologetically, but then he could not have successfully led a militant organisation like the Shiv Sena otherwise. He brooked no dissent, but listened closely to second-tier leaders like Pramod Navalkar, Manohar Joshi, Sudhir Joshi, Chhagan Bhujbal, Dattaji Salvi, Liladhar Dake, and others.

Bhujbal revolted when he felt that Joshi was being promoted at his cost, but the defection made little difference. The Sena withstood the defection of even Raj Thackeray. Narayan Rane, whom he promoted as CM too, betrayed him.

Also Watch:

Legacy and personal bond

Balasaheb, who faced several personal tragedies, had a fondness for his son Uddhav, who subsequently became chief minister. Balasaheb was not there to witness Uddhav being sworn in. But I am certain that he would not have sat on the CM’s chair even if Uddhav had requested him.

To get details on exclusive and budget-friendly property deals in Mumbai & surrounding regions, do visit: https://budgetproperties.in/