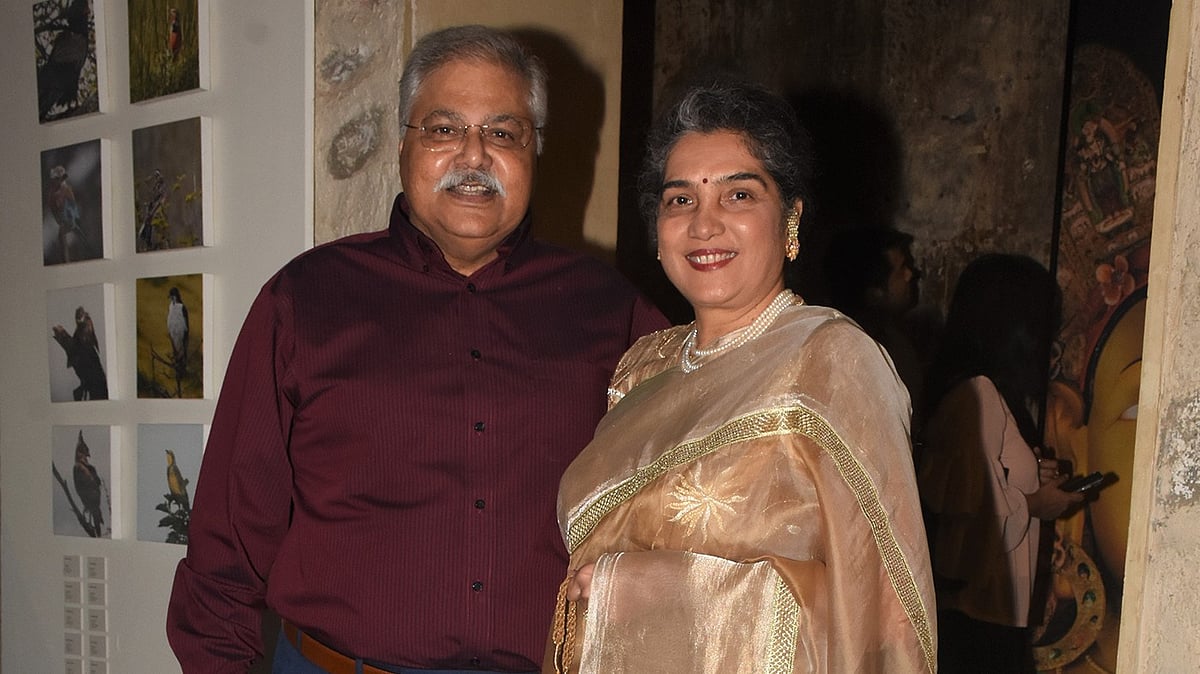

In the age of information it is difficult to imagine a time when communication was by landline telephones and snail mail. Now imagine an epidemic breaking out in such a time. When the human immunodeficiency virus struck, spreading insidiously all over the world, it took a while for India to wake up and realise what a terrible disease it was. At the forefront of the fight against HIV and AIDS was a young doctor, Ishwar Gilada. Dr Gilada’s lifelong commitment and immeasurable achievement in this battle has been detailed with stories and photographs in a book, The Blunting of an Epidemic: A Courageous War on AIDS, by journalists Jayashree Shetty and Gopal Shetty.

We caught up with the indefatigable Dr Gilada for a quick chat ahead of World Health Day, April 7.

When did you launch the war on AIDS, and what was it like then in terms of resources, facilities, knowledge and awareness?

I started working in JJ Hospital in 1981 in the Skin and STD department. Within a couple of months I realised that the patients were mainly men; there were hardly any women. Every man said he had picked up an infection from the red-light area. I discussed this with the head of the department, we spoke to the administration, but since the attitude of the government was not conducive, within six months I had started my organisation, the Indian Health Organisation (ILO), now known as the People’s Health Organisaton, a registered public trust. It was set up on April 7, 1982. Along with my colleagues I held health camps – the first camp was in Dharavi in June 1982, and the second was in the red-light area later that month.

When we started treating and testing the people there, we found that many of the women had more than one infection – and the general attitude was one of shunning them but the fact is that they were getting infected from the same society which was blaming them. It was a high-risk area – but at that time I did not think that HIV would hit India. No one did.

At that time (I was in my 20s) I was monitoring HIV in the international media, reading whatever I could. In September 1985 I spoke at a health education conference in Dublin. There was also a session on HIV at the conference, where one of the scientists said HIV would hit continents other than Africa and the US, and that doctors are not yet aware. I came back from there and distributed a short questionnaire for doctors in India — and realised that most doctors didn’t know what is HIV or AIDS. This made me realise that we must definitely be missing cases. On September 22, 1985 we had a press conference to say that HIV might be present in India and that doctors may not be aware of it. This created consternation, but it was a good beginning. The international media picked it up, though the government was still saying that HIV was not a problem in India.

One of the global articles, in TIME magazine, was read by someone from Abbott Laboratories, who got in touch with me and offered me 1000 test kits. Thus I offered to start an HIV clinic, with no financial burden to the government. We focused on testing key groups — sex workers; people who get regular transfusions like haemophilia and thalassemia patients; and those who donate blood regularly. I used to do these tests after my regular work at JJ Hospital. When I found positive samples I reported to the government. The samples were sent to the National Institute of Virology in Pune where the positive result was confirmed. Still, NIV sent them to CDC Atlanta — where also they were found to be positive. In all this it took months to officially declare cases as positive.

For two to three years after this we focused on education of the medical community and of high-risk groups, and mass awareness among people — holding rallies, exhibition at train terminuses, programmes in educational institutions, workplaces, and on the streets. In this way awareness grew and got better. But the problem was a virus bigger than HIV – and that was jealousy. Because of the publicity that my work was attracting, colleagues as well as government officials questioned my name appearing in the papers. I eventually got fed up with the attitudes and resigned from government service in December 1990.

Your main point was the use of condoms in the red-light areas to stop the spread of the virus – how did you decide on this course of action, and has this become an established practice now?

We found that HIV was spead in three ways – from mother to child, through blood transfusion, and through sex work which constituted about 90 per cent of the spread. There was no testing done for the first two, so we focused on prevention through the red-light area. We tried as much as possible to educate men not to go to sex workers. But this is just not possible or feasible, so we told them that if they had to go to sex workers, then to perforce use protection. we emphasised the multi-faceted usefulness of the condom; that it would not only protect them from other sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) besides HIV, but also prevent the possibility of an unwanted pregnancy and a resultant unwanted paternity for the man. Basically we told them, “Be good. If you can’t be good, be careful!”

Now, HIV treatment has become so effective that the virus is undetectable in viral load – which means that even if it is present, it is not transmittable. However, the importance of condom promotion is not diminished, as STDs are still prevalent, and condom use is the only way to prevent these.

What are general attitudes like now, towards HIV/AIDS and towards patients? If an AIDS vaccine becomes easily and affordably available, do you think everyone should take it?

Even now there is discrimination towards HIV patients, and in India this is mainly because of the double standards in society. Since sexual contact is one of the modes of transmission, our attitudes towards sex get transferred to the disease and its patients. Thus the stigma related to HIV will never completely go away because of the stigma related to sex. An AIDS vaccine would have to be as cheap as, say, the hepatitis vaccine – so that each and every one could afford it.