This book documents the journey from a time in which cinema was considered a profession beneath the dignity of ‘respectable’ women to an era when women actors are icons and idols. Also riveting are the first-person narratives of a leading actress from each decade.

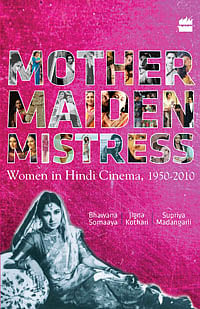

Mother, Maiden, Mistress: Women in Hindi Cinema 1950-2010

Bhawana Somaaya, Jigna Kothari & Supriya Madangarli

Harper Collins

Pages: 247; Price: Rs. 299 |

As India celebrates the centenary of Indian Cinema, many would understandably want to know how the film industry progressed over the decades beginning May 1913 when the first film ‘Raja Harishchandra’ was shown to an enraptured audience in Mumbai.

The world had changed. A greater change was to come when, in April 1931, barely two decades later. Mumbai was again to watch, this time a ‘talkie’, Imperial Film Company and Ardeshir Irani’s ‘Alam Ara’. A newer, brighter world had come into existence, which was to revolutionise society.

At first Indian women were unwilling to act in the films. The female roles first became the preserves of Anglo-Indian or women of Jewish origin like Sulochana (Ruby Myers), Pramilla (Esther Abrahams) and Fearless Nadia (Mary Ann Evans), but then came Durga Khote, a highly-educated Brahmin girl, Devika Rani and Shanta Apte of Prabhat Talkies who brought new life to the Indian screen.

The era of the Studios offered an eclectic fare – social drama, costume and stunt films (adventure stories and revenge saga) and, in the late 1930s and 1940s, nationalist fi1ms. Contemporary India and its class distinctions also began to be presented. By the 1950s Indian films were beginning to make an impact globally and this became exceptionally evident by the sheer popularity of Raj Kapoor’s ‘Awaara’ which captured the imagination of the Russian youth as nothing else had been done before. Its theme song became the song of the times.

According to the authors of this remarkably well-researched work “it was in the 1950s that the dialectic of mass entertainment versus class entertainment developed”. Significantly in the 50’s the passionate kissing scenes of the early silent films became history, and just as significantly, it was still not considered respectable for women from good families to join films as heroines or actresses.

Then came the 60s. This saw the “upbeat, optimistic mood of a new generation of Indians” as was apparent in the song: ‘Chhodo kal ki baatein, kal ki baat puraani, naye daur mein likhenge milkar nayi kahaani, hum hindustani’.

As the authors see it “the 60s will be remembered as the decade of the romantic musical and some of the plots became so popular that their recurrent usage turned into a ‘formula’.

Furthermore they claim that while in the 50s Raj Kapoor had focussed on the individual’s relationship with society and the accompanying chaos and pathos, “by the sixties his films had shifted “to the individual’s personal relationships and the resultant sexual tension as seen in ‘Sangam’ (1964). The decade, claim the authors, also saw changes in technology and the introduction of colour “which infused a spirit of invention and experimentation into the dressing room”.

Then came the 70s. This was a decade, according to the authors, when ‘liberation’ for the urban crowd meant looking inwards and “sexual revolution and experimentation became the key-words of the then generation”.

Art house films gave a political identity to the “dispossessed and disenfranchised”. In he mainstream cinema the age-old depiction of ‘Indian’ values versus ‘western’ ones continued to focus on the cultural decadence of westernised women and how they were punished for it”.

Films, note the authors, were dominated by male super-stars and women were often reduced to uni-dimensional figures and relegated to supporting cast status with nary a sub-text. But, the authors insist, “there was an eagerness to explore and an easy acceptance of change and new ideas”.

It was a “tumultuous period” with “peaceniks, hippies, new age religious movements, feminism, activism” ruling the prevailing air, with a society in search of freedom. It was a decade when the Angry Young Man established himself as the voice of the cinema and the masses.

Came the 80s with now te1evision coming into its own. The authors now note, “dominated by family socials and regressive characters and story lines, commercial cinema in the eighties went through what is known as the ‘dark age'”.

Form and content lost originality and films, the authors say “assembled Vaudeville entertainment, consisting of big-budget song numbers with fantastic sets, comedy sketches that at times had nothing to do with the plot…”

Films of the early nineties do not seem very different from those of the earlier decade, with most films characterised by lavish sets, elaborate song sequences, fantastical and often caricaturish villains with ponderous dialogues.

At the same time, as the authors saw the situation, the nineties was a time when the film industry went through an identity crisis, with formula films failing to attract crowds. What is remarkable is that the film that went on to become an official block-buster surpassing Ramesh Sippy’s ‘Sholay’ was Sooraj Barjatya’s ‘Hum Aapke Hain Kaun’ (1994). The movie, write the authors, though dismissed by critics as a wedding video, was hugely appreciated by the masses and went on to break several records and set new milestones at the box office.

With the end of the nineties came the Millennium. For the Hindi film industry, this brought in radical changes that shook the structure that had been con-cretised since the fifties.

According to the authors the Indian film industry was officially recognised as an industry and films began to work on a business model. With 500 television channels and 69 private (FM) radio stations, com-petition had become very severe. For filmmakers there grew a new class of viewers receptive to innovation. Small budget films came to be in fashion.

What is remarkable about this work is the attention given to every important film of each period to draw legitimate conclusions. To remember each film, its casts, its dialogue, its music, its theme, its direction and finally its total attraction, is an achievement in itself. Bhawana Somayya, of course, is an old hand, having been a film critic for over three decades. Supriya Madangarli has apparently spent five years in doing research for this book – and it shows. The same is said of Jigna Kothari.

This is a fabulous work, the first of its kind, deserving all praise. Particular stress has been of course, on women stars, but then that is what the authors wanted to lay stress on and they have done a beautiful job.

M V Kamath