In every age, humanity has found a way to separate the privileged from the punished. In older civilisations, it was by birth or bloodline. In modern times, it is by access—to capital, to trade, to technology, and to the right to participate in the global order. Today’s world has perfected a new form of that ancient impulse. The sanction has become our contemporary caste mark.

For decades, we told ourselves that the twentieth century had birthed an architecture of fairness—a system of treaties, multilateral institutions, and shared norms that would prevent the strong from preying on the weak. The United Nations, the World Bank, and the WTO—they were meant to be neutral arenas for resolution, not tools of coercion.

Yet, quietly and almost imperceptibly, that belief has been eroded. Sanctions have replaced dialogue. Access has replaced equality. The right to transact, to move goods, to borrow, and to learn—these have become privileges controlled by a few powers.

What began as a supposedly moral instrument—a way to deter aggression or human rights violations—has become the default language of dominance. The sanctioning power decides what counts as aggression, what counts as morality, and what constitutes compliance. The modern sanction does not strike like war.

It works like quarantine. It isolates a nation, not through guns but by denying entry to the world’s bloodstream of finance and technology. When a country’s banks are cut off from global payment systems, when its ships are barred from ports, when its students are denied visas and its scientists cannot collaborate—that is the silent violence of modern geopolitics.

There are the “upper orders”—nations that sanction, whose currencies dominate, whose systems clear global payments, and whose corporations can trade anywhere. Beneath them are the “intermediates”—those that obey and align, who participate under supervision, careful not to offend the hierarchy. And then there are the “excluded”—states frozen out of the system, forced to find barter routes, grey markets, and new alliances. These are the untouchables of global commerce.

Unlike war, which ends with a treaty, sanctions have no natural closure. They linger. They tighten with each passing year. A state can comply fully and still find the doors only half open. The fear of re-imposition hovers like a shadow, ensuring obedience long after the supposed transgression has passed. This permanence gives sanctions their caste-like power.

For those caught in this web, the consequences are devastating. Entire economies are starved of investment. Currencies collapse under the weight of isolation. The everyday citizen becomes collateral damage in a geopolitical morality play. The elites adapt, finding loopholes or alternate channels, but the middle class and the poor bear the brunt of exclusion.

As the sanctioned world learns to survive, it also begins to reorganise. Parallel systems are being built—new payment networks, new trade corridors, and new alliances that operate outside the traditional Western-dominated order. Russia and China have moved their energy and financial relationships eastward and southward. Iran trades oil for goods, bypassing currencies.

Smaller states, watching this slow bifurcation, hedge carefully—afraid to anger one side but unwilling to remain forever dependent on the other. The result is the global economy no longer resembles an open network; it resembles a map of gated communities.

And as this new order hardens, multilateralism withers. The old promise—that disputes would be settled through negotiation and that international law would restrain power—now feels like an echo from another century. Institutions built to ensure fairness are now bypassed or, worse, used selectively. Rules apply to some, discretion to others. The language of equality still lingers in communiqués and speeches, but its meaning has thinned.

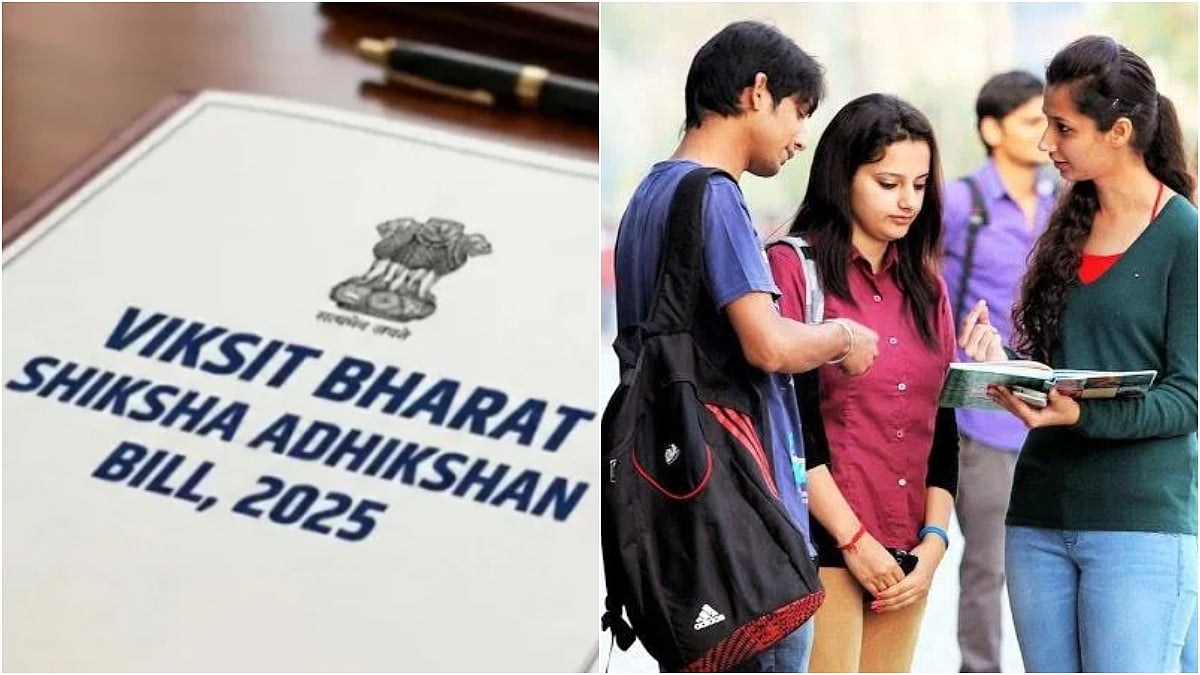

In this stratified world, neutrality itself becomes an offence. A country that tries to stay non-aligned is pressured, warned, and sometimes threatened. The global South, which once found agency in collective platforms, now faces individual coercion. Each state must decide whether to risk exclusion or conform to a system that treats them as dispensable. The idea of a truly multipolar order—one in which regions could balance interests without fear—is being replaced by a duopoly of access and absence.

Sanctions are justified as humane alternatives to war, yet their long-term toll on societies is often deeper and quieter. The denied shipment of insulin kills as surely as a bullet. The isolation of young scholars, cut off from research and collaboration, stunts an entire generation. It is a moral crisis.

A world built on exclusion cannot be stable. Every wall provokes a counter-wall. Every hierarchy breeds resistance. The sanctioned nations of today learn quickly to trade among themselves, to build alternative institutions, and to mistrust those who lecture them about rules they never wrote. The more the hierarchy tightens, the faster the promise of a common order dissolves.

If the twentieth century’s dream was one of multilateral cooperation, the twenty-first is veering toward stratified control. The caste order of sanctions is undoing the moral architecture of the global commons.

Sanctions should have been a pause—a temporary restraint to compel peace. They have instead become a permanent sorting mechanism. The challenge before us is not merely to lift them but to question the logic that sustains them. If the world continues to organise itself by exclusion, it will not be power that wins, but fear. Will we have the courage to restore the fragile promise that the world once called multilateralism?

Dr Srinath Sridharan is a policy researcher and corporate adviser. X: @ssmumbai