Though 84 years have passed since the first tribunal for income-tax disputes was established, India still does not have a comprehensive system to govern the functioning, composition, and independence of tribunals. Over the decades, new bodies have proliferated—the Armed Forces Tribunal, the National Green Tribunal, and various administrative tribunals—each meant to reduce the burden on regular courts.

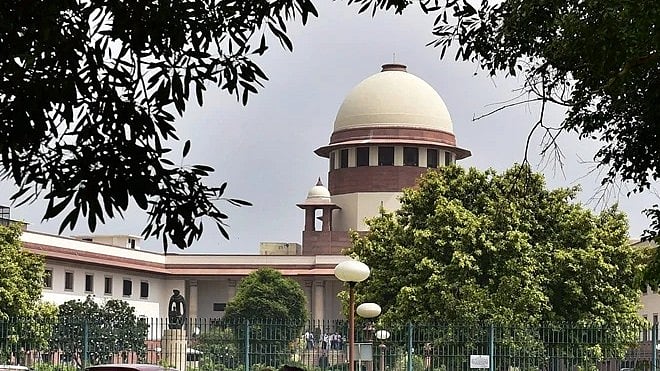

Yet, ironically, they continue to function without any central authority to oversee or standardise them. It is against this backdrop that Wednesday’s landmark judgement by a Supreme Court Bench headed by Chief Justice BR Gavai must be seen. The court struck down the Tribunal Reforms Act, 2021, a law that had replaced an ordinance earlier invalidated by the judiciary.

In unusually vivid language, the Bench described the legislation as nothing more than a cosmetic retouch of the discarded ordinance: “The Tribunal Reforms Act, 2021, is a replica of the struck-down ordinance; old wine in a new bottle. The wine whets not the judicial palate, but the bottle merely dazzles.”

By rejecting the law and reviving the pre-existing rules, the court has laid down a clear directive: the Union government must constitute a National Tribunals Commission within four months. Such a body, if truly independent, could finally provide consistency and credibility to the functioning of tribunals across the country. At the heart of the conflict between the government and the judiciary is the question of appointments.

The government’s insistence that only those above 50 years can serve as tribunal chairpersons or members is an arbitrary restriction that shuts out younger talent and contradicts the broader need for fresh perspectives. Equally contentious is the court’s reluctance to accept scenarios where technical experts outnumber judicial members—even in specialised bodies like environmental tribunals. The message is clear: tribunals must remain judicially anchored.

The verdict made the point the enormous backlog of cases in the courts is not solely the judiciary’s fault. Successive governments have contributed to delays through inadequate infrastructure, poor staffing, and legislative ambiguities that generate avoidable litigation. Significantly, the judgement challenges the notion that Parliament’s authority in law-making is unassailable.

The Constitution empowers the Supreme Court to examine the constitutional validity of any law and even strike it down. This is part of the basic structure, and no legislative assertion can override it. The central theme of the verdict is unmistakable—the appointment of tribunal members must be insulated from executive control. If those adjudicating disputes with the government are answerable to the government, justice itself is compromised.

The court’s prescription resembles the collegium system of judicial appointments, a mechanism far from perfect but still trusted more than any alternative proposed so far. It is in the nation’s best interests that the executive, the judiciary, and the legislature work in harmony, guided always by the rule of law.