Just glance through the main recommendations of the last education policy brought out by the Kothari Commission (1964-66). Then compare it with the National Education Policy (NEP) brought out recently by the government of India.

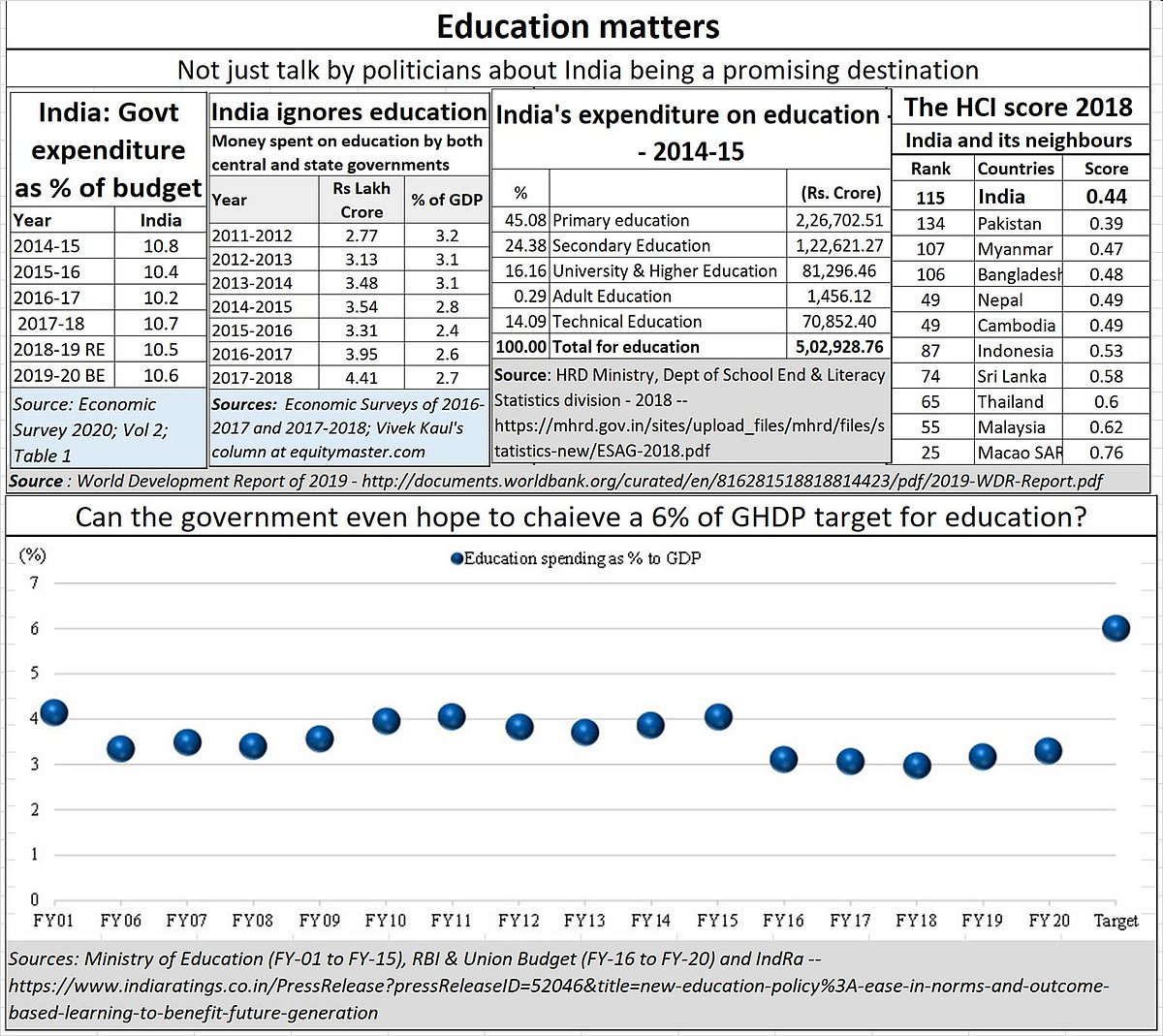

In both policies, you will find the exhortation that more (6% of GDP) should be spent on education. Yet, the truth is that successive governments have spent little on education. With little vision and less learning, India has tried to push through an NEP that has many similarities with the views of the Kothari Commission.

In 1964, when India was still struggling with basic necessities, the inability to spend was understandable. But today, when India talks about being a world power, this poor spending on education is scandalous, even criminal.

Worse, in the NEP of 2020, you will also find a bit of dogmatism, even prejudicial approaches. And you will also discover a great way to dream and fantasise. You could even call it hallucinating.

Consider for instance that India’s ranking on the HCI or the Human Capital Index. And then look at the NEP’s faith in government spending. Touching indeed!

The good

Yes, the NEP has some very good parts.

It includes pre-school education in the main education structure. This allows for two things.

First, it seeks to regulate an unorganised, unregulated, and even profiteering part of education, sometimes with very unhealthy linkages to primary school admission in urban centres like Mumbai and Delhi.

Second, it allows for the mid-day meal being extended to pre-school children right from the age of three. In a country where 50% of children are malnourished, this will be a big benefit. As any nutritionist knows, if proper nutrition is not provided to a child at the age of 3, brain development suffers. This measure alone will benefit millions of children across the country. But whether this will mean an upgradation of skills, certification, and salaries for the 1.2 million anganwadis remains to be seen.

Another good thing is the focus of the NEP on the all-round flexibility in course structures. But then this was suggested by the Kothari Commission as well. It talked about vocational courses even then. The 10+2+3 was devised so that children could opt for vocational courses after the 10th standard examination. This author was on the sub-committee advising the Maharashtra State government on vocational courses during the 1970s, and it was distressing how these courses were sought to be taught at the +2 stage, in classrooms, without any exposure to workshops or fieldwork. There is no guarantee that this won’t happen again. True, the government has modified the 10+2+3 into 5+3+3+4. It remains to be seen how the 1.5 million schools adapt to this new structure.

The bad

Then come some not-so-good parts.

The NEP is full of impressive phrases like holistic and multi-disciplinary. Yet scratch at the paint, and you can see signs of fundamentalism and prejudice.

The irony is that even while Chinese universities encourage the learning of Indian languages, India prefers to do without such learning.

Take another example. The Kothari Commission was emphatic that English should be the link language in higher education for academic work and intellectual inter-communication. Hindi could also be a link language. But it advocated a three-language approach. A focus on regional languages, any other language approved as an official language by the Union of India and a foreign language. There was no prescription or exclusion. The first draft of the NEP actually tried to make Hindi a compulsory language and backed off only in the face of stiff opposition from all the southern states.

It is dangerous to dismiss English. It is becoming increasingly relevant for corporate and financial worlds – not just in India, but globally. That is why Germany insists on courses in English, as does China. That is why even housemaids want their children to study English. They know market realities which politicians choose to ignore. And don’t even think of changing the language in Indian courts, because there are not enough precedents or case studies for fords in other languages. It will make judicial redress even more complicated than it is now.

And there are some ugly parts to the NEP as well. But those will be dealt with in the second part of this article.

To view the Kothari Commission education policy, please visit www.freepressjournal.in

The author is consulting editor with FPJ