Having to take a short cut through the fields once, I asked a small boy tending cows whether a walk in that lonely place was safe. “Oh yes” the boy replied at once, “the CRP – Central Reserve Police – have gone!” That was in rural West Bengal at the height of the Naxalite movement nearly 50 years ago.

But the oppressive image of the police and para-military forces remains much the same. Indeed, TV depictions of the barbaric treatment of people at the start of the 21-day lockdown demonstrated that the basic character of the police has not changed since the British created it under the Councils Act of 1861, only four years after the uprising of 1857 was suppressed with the utmost brutality.

The police were meant to control rather than protect and suppress rather than support the locals. Of course, earlier rulers like the Mughals, Lodis and other royal dynasties also had their police.

Some Indians even trace the force back to the Rig Veda. But today’s police are derived from the force that the British Raj created as the empire’s first and largest colonial-style instrument for maintaining law and order. Ireland being Britain’s backyard and first colony, the Royal Irish Constabulary was the model for many experiments in colonialism whose results were exported to Asia, Africa and the Caribbean.

No one will deny that the police have a far from easy task in India. How they sometimes discharge that task was horrifically highlighted by what has become notorious as the Bhagalpur blinding in 1979 and 1980 when policemen blinded 31 individuals by pouring acid into their eyes.

Some say the victims were under-trial prisoners; others maintain they had already been convicted; according to a third version, they were hardened criminals who enjoyed protection and whom the law could not touch. Whatever the truth, the infamous Bhagalpur blinding could not and should not have occurred in a civilised society.

That it happened some 400 km from Calcutta was an indication of the extent to which Indian society had been brutalised. No one has been blinded yet in the present round of violence, but a woman doctor bent on essential duties was slapped by a police officer and abusively jeered at. "With whom are you going to sleep at this time?" he asked.

Pictures and videos have emerged from around the country of people being brutally hit by lathis, of doctors being assaulted and of vegetable vendors slapped around by policemen demanding bribes. While such abuses have been reported from Delhi, Mumbai and Hyderabad, the Punjab police appears to have incurred the wrath of many viewers.

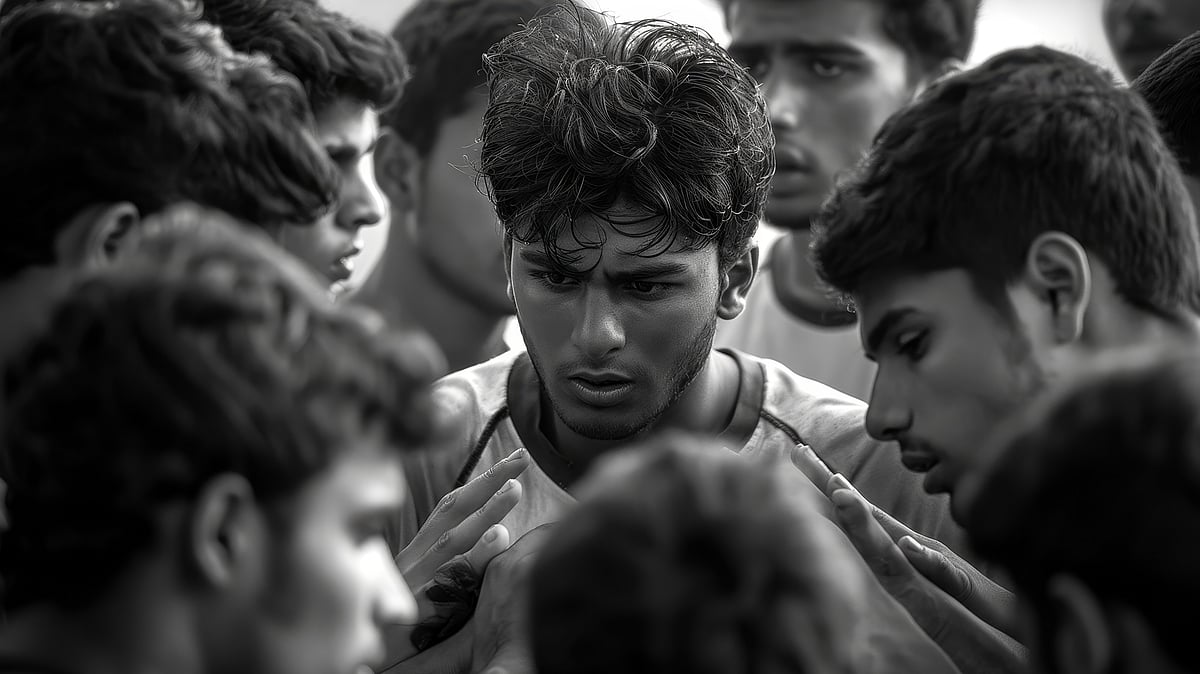

Policemen have been shown not only thrashing young men with their lathis but torturing them in many ways – making them do push-ups and toe-touching within chalked circles, forcing them to crawl on their knees or roll along on the road like some Hindu pilgrims.

Delivery personnel for essential goods and vegetable vendors have also been beaten up. If this was punishment for violating lockdown norms, no such punishment seems to have been meted out to Adityanath, the Bhartiya Janata Party’s saffron-draped chief minister of Uttar Pradesh, for participating in a religious ceremony in connection with the proposed Ram temple where the now destroyed Babri Masjid once stood.

In another situation in Deoria in the same state, a self-styled god woman known as “Maa Aadi Shakti”, draped in a red and gold saree, pointed a sword at policemen on Wednesday, and refused to call off a religious gathering. However, not everyone is so favoured.

Reports indicate that a retired police officer and one still in service have been booked for violating mandatory social distance norms by celebrating family weddings. Perhaps they thought they could get away with it. But considerations like community, place of occurrence and party in power may not have favoured them.

Today, the unquestioned loyalty the police once gave to India’s alien rulers is lavished equally unquestioningly on the political party in power as part of a vicious – if unspoken – compact that has done much to damage the quality of life. In return for serving the politicians’ ends, policemen can make hay on their own account on the side. That little boy I spoke to in a Bengal village innocently reflected the views of millions of adult Indians.

The police were designed for foreign conquerors to rule over a native population. Its composition was racial, its form hierarchical and its purpose to keep the natives in their place. The composition may have changed to some extent (although many North-east Indians may dispute that) but the hierarchy persists. And far from being the protector of the populace, the police are perceived in many parts of the country as one of the worst oppressors. Discipline was strict and militaristic.

With British officers at the top, hierarchy was reinforced by race: the white men demanded unquestioned obedience from those below. Typically, Eurasians – men of mixed British and Indian descent – dominated the lower supervisory ranks for, being complex-ridden and seeing themselves as white, these sergeants and inspectors could be relied on to treat the natives with the utmost harshness.

Indians who formed the rank and file and were in the largest numbers were put on a tight leash. They were isolated from the community at large in residential barracks with special uniforms and ranks to ensure (and reward) discipline and loyalty. They were also granted powers that would not be questioned when abused and benefits that separated them from the masses. Being posted far from their own villages and communities isolated them.

The mutual suspicion between the police and the masses that this generated survives to this day. As India faces a potential rise in the number of coronavirus cases and as millions worry about how they will access basic needs like food and water during the prolonged shutdown, Indians have to face an additional worry: the fear of arbitrary state violence, even for those who are out on the streets for a good reason.

This is a challenging moment for the police. It is an even more challenging time for the public. Most important, however, it’s an opportunity for governments, central and state, to change their approach to the relationship between rulers and ruled and remind the police that persuading people is more effective in the long run than trying to beat them into submission.

That demands a thoughtful and compassionate political leadership that understands how to convey to people that they should stay indoors for their own good and not only as a matter of obedience to brutal authority.

The writer is the author of several books and a regular media columnist.