Last week, the governor of the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) announced that it would allow the linking of credit cards with UPI (the Indian government’s amazing introduction of a Unified payment Interface). The UPI has done amazingly well in Indian transactions, both in terms of volumes and even transactions.

Clearly, the RBI now wants to expand the use of UPI even further by linking it to credit cards. Hitherto, UPI has functioned as a debit facility, akin to debit cards.

The strategy looks good. But there are some major problems.

Story time

But to get there, here’s a real-life anecdote. I had to pay non-agricultural tax (NA Tax) recently introduced by the government of Maharashtra for city based residential properties. I found the introduction of this tax highly unfair. But since the law was binding on everyone, I paid up the money. I chose the credit card route.

I have a VISA card, and when I went to the NA tax website, the site crashed just after I had given my OTP details. It said that I had been timed out. I tried again. Once again, after giving the OTP details, the site crashed, stating that some referenced number could not be obtained. Five minutes later, I got a message on my phone informing me of two (not one) debits.

I was flummoxed. Luckily, I had taken screenshots of each stage of the transactions (you can download them here). I sent these to the government officer concerned. I asked her for a receipt for the payment that had been made. I also asked her for a refund of the additional amount debited to my credit card.

She informed me that the receipt would come in a couple of days, but that refunds cannot be made by the government. She said that the amount would be adjusted against forthcoming bills. This was shocking. The bill was for taxes applied with retrospective effect from 2006. To adjust the amount would take at least a decade.

I decided on complaining to the bank instead. I requested the credit card issuer to repudiate the transactions because the government website malfunctioned. I sent the supporting screenshot evidence. I knew that VISA and Mastercard allow for chargeback if a customer can prove that he was not at fault, and that the debits were wrongly made.

The credit-card issuer refunded me both the debits (not just one) as an ad hoc measure till the other bank could prove that my allegations were untrue. It sent a letter to the other bank, which had to respond within three months. The response did not come. The refunds stayed with me. The government, in the meantime, cancelled the levy of this tax, even as the courts began hearing the case.

All the people who have paid the government are still waiting for a refund. I have got my refund, because I made by payment through VISA/Mastercard. I do not think I would have got my money back if I had paid through Rupay (the government backed credit card, introduced by NPCI) . This is because NPCI does not maintain logs of transactions. And it is not duty-bound to pay heed to calls for chargebacks.

I wrote to NPCI asking me if dispute resolution would be allowed, but got no reply. I asked it if it would now keep a log of transactions once credit cards are linked to UPI. I got no reply.

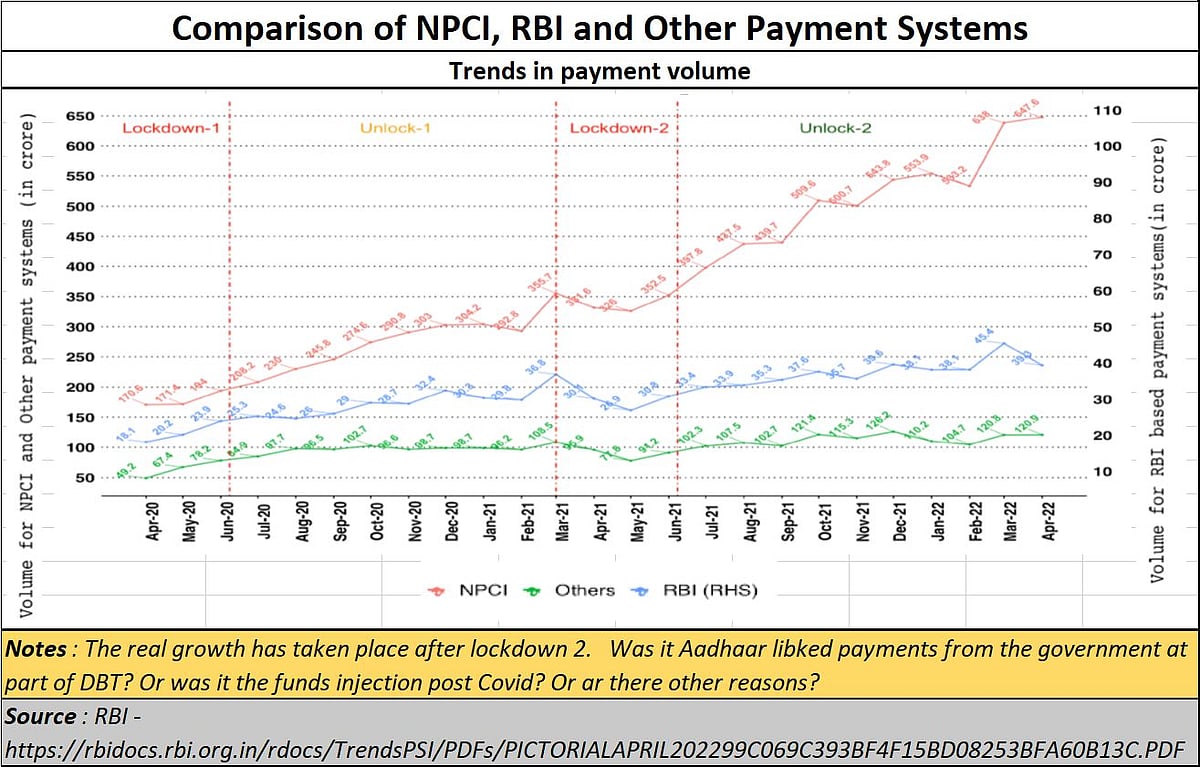

For now, the RBI the government and even NPCI are rubbing their hands in glee at the runaway success of digital payments, mostly through the UPI and the Rupay.

And if one considers other indicators, even the RBI index shows how digital payments have grown.

However, this anecdote taught me some key lessons, which India’s policymakers also need to learn.

Lessons

First, unless customers’ interests can be protected, introducing new payment mechanisms is dangerous. UPI and NPCI do not protect customer interests. They do not allow for dispute resolution.

That is why, I continue to make payments through VISA or Mastercard, not through Rupay. NPCI’s refusal to reply to queries relating to customer interests is itself a gross violation of consumer protection norms. Its officials must be taught how to respond to queries. Silence is no solution.

Second, any financial player/regulator that believes it can be a legitimate player without keeping logs of transactions is pulling wool over the eyes of customers. How can any credit card billing be possible without maintaining logs of payments, debits, and credits?

The basic rules behind NPCI’s functioning violate the basics of financial discipline. Only hawala merchants are taught not to maintain any logs of transactions.

Third, all financial systems involve a cost. VISA and Mastercard can protect customers because they earn a merchant discount rate (MDR). Rupay functions with zero MDR. Customers and merchants are happy because they do not have to pay such changes directly or otherwise.

But ‘free’ can be extremely expensive. When it comes to dispute resolution, a zero MDR does not offer the bandwidth for the backroom work to be done.

The RBI’s intentions may be laudable. But it has not reckoned with the basic flaw in NPCI’s workings.

Where is the regulator?

The biggest flaw is not bothering to protect customers. Can any financial service function without respecting this cardinal principle?

And this brings me to the last point. For the past decade or so, people have been clamouring for an e-payment regulator. There is no sense in permitting transactions at the speed of light, but with a dispute resolution mechanism that is either missing, or too time consuming.

Had there been a regulator, it could have hauled up government departments for flawed and malfunctioning websites. It could have penalised software companies that do not ensure that income tax portals and GST websites are customer friendly. It could even have penalised developers of banking software platforms for allowing transactions without first recording them in the central registry.

Any manual override should have triggered alerts which should have been sent automatically to the finance ministry and the RBI investigation department as well.

Many of the scams could have been avoided if there had been a regulator for epayment and transactions systems.

So, why has the government not appointed an epayment regulator as yet? Is it waiting for a crisis to happen first?

The author is consulting editor with FPJ