March was supposed to herald spring, the lyrical and pleasant Basant. Instead, it brought summer-time heat to Mumbai this year as temperatures hovered in the high 30s. The month of March last year had seen Mumbai’s maximum temperature nearly touch 41 degrees Celsius, a good 7.7 degrees above normal. In the decade 2011-2021, the city’s maximum temperatures had breached the 40-degree mark at least five times and hit the high 30s many times over. It’s time to acknowledge that Mumbai is well and firmly in the grip of the urban heat phenomenon.

The city is saved, to an extent, by the sea breeze which substantially cools it down and takes away the sting of the heat – though brings in humidity – there’s no getting away from the fact that, like urban flooding, we must also contend with urban heat and its impact in the decades ahead. Just as its low-lying areas are vulnerable to inundation during monsoon, the city is also susceptible to increasing maximum temperatures resulting in heatwaves. The focus of mitigation measures tends to be on the annual floods, with good reason too, considering the large-scale impact on lives and work, but a similar level of attention is called for on urban heat too.

Mumbai needs its own comprehensive Heat Action Plan sooner than later. The evidence has been piling up: Studies by IIT-Bombay show that surface temperatures in certain densely-packed areas can be up to eight-nine degrees Celsius higher than in the rest of the city or its periphery, other studies demonstrated that the average temperatures have risen by nearly two degrees in the last 20 years, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) reports are clear on the phenomenon.

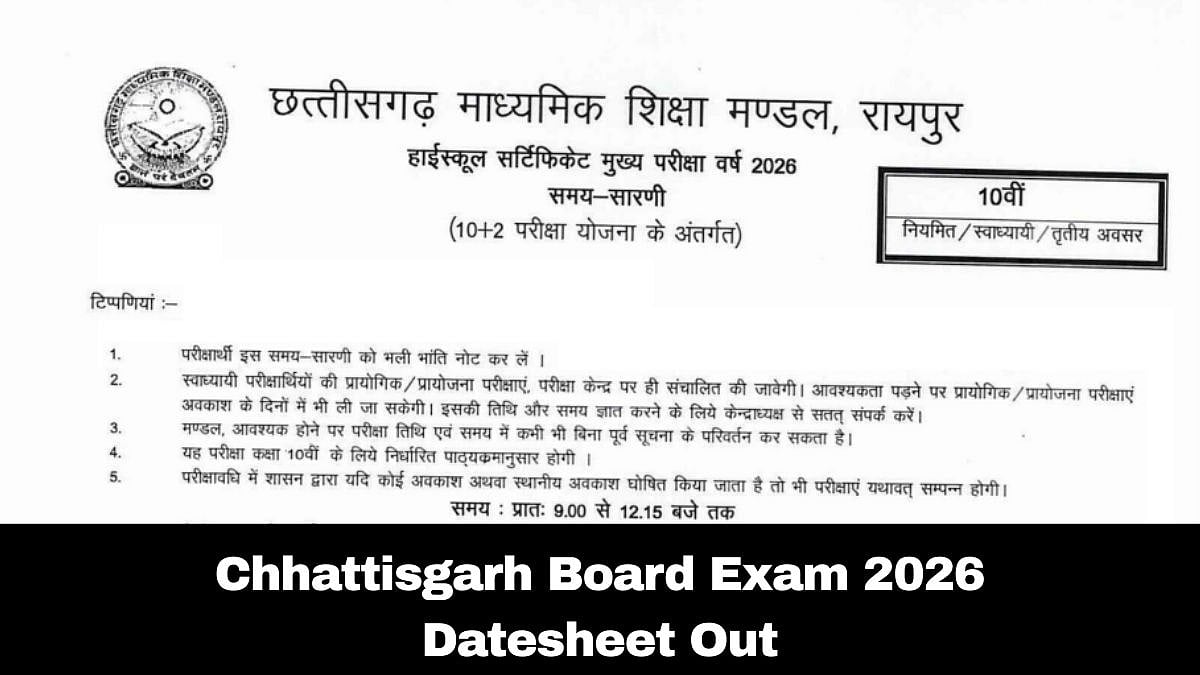

In fact, every major city needs its own version of the Heat Action Plan and must be pushed to evolve one without delay. An IIT-Kharagpur study that examined 44 cities across India from 2001-2017 showed how they are turning into urban heat islands across seasons. The union health ministry has begun collecting data on heat-related illnesses (HRI) and deaths due to HRI. In 2015, data on these parameters poured in from as many as 17 states. The number had increased to 23 states in only the next four years.

The health ministry, with assistance from expert groups and an empowered committee, unveiled the National Action Plan on HRIs in July last year. However, it has not quite caught the fancy of city administrations or inspired debates; it hardly found space in the media. It acknowledges that at least 3,771 people died from HRIs in four years in the most vulnerable states, and lists out a spectrum of disorders from heat rash, heat cramps, heat exhaustion, heat syncope, and heatstroke. There are no diagnostic tests to ascertain a heat stroke or the fatality it causes, it observes and compiles a detailed set of standard operating procedures and guidelines for health services – mainly hospitals – to detect, report, and treat HRIs.

The Plan needs more debate and engagement from both city governments and people themselves for it to make an impact. Yet, it will be limited to the health consequences of urban heat. What it is not, and does not claim to be, is a comprehensive plan to combat the immediate impact of urban heat across India’s cities, detail mitigation measures and fix responsibilities on city governments or municipalities, and work out adaptation measures in the long term. It may not be feasible or advisable to have a national comprehensive heat action plan to cover all of India’s cities – it is indeed more practical for municipal corporations or councils to evolve city-based plans – but given its awareness of at least the health outcome of rising urban heat, it may be a good idea for the central government to evolve a template that can be shared with all states or cities.

A few cities like Ahmedabad and Nagpur have had their own Heat Action Plans for some years now their scope and implementation leave much to desire. The Ahmedabad Heat Action Plan was put in place after the deadly heatwave in May 2010 in which nearly 800 excess deaths were reported in the city in only a week – of a total of 1,344 in that month – and has been updated several times since. Its components across the years have been the following: An early warning system, public awareness, and community outreach, inter-agency emergency response mechanism, capacity building of medical professionals and hospital networks, reducing heat exposure, and promotion of immediate adaptive measures such as cooling centres and drinking water facilities.

The Plan has drawn criticism for its short-sightedness and indifferent implementation. The poorest tend to be most vulnerable to climate change events and suffer the worst impact of the heatwave then and since, but they could not always access the services or specific measures. Other actions such as no outdoor work in the searing afternoons or compulsory time-out are rarely considered. Ahmedabad has reported fewer HRI deaths in the last few years though the pandemic did keep people indoors. The criticism in Nagpur is that the municipal corporation has merely trotted out good old Do-Don’ts advice to citizens as part of the plan without concrete measures undertaken by the administration to help combat the climatic condition. It’s akin to telling people to stay at home during heavy rains as part of a flood action plan.

For what it is worth, these cities at least have Heat Action Plans. More cities across India must evolve their own. In the Mumbai Climate Action Plan released recently – which earned state minister Aaditya Thackeray applause and criticism in equal measure – there is acknowledgement of the urban heat phenomenon but it gets scant attention on the mitigation-adaptation aspect. There’s mention of more natural cooling measures, a pilot for using green cover and ‘cool’ roofs in the most vulnerable areas, making heat-resistant roofs and wall materials mandatory in new building structures, and so on, but these are bandaids on a bleeding wound.

The MCAP makes a note of the staggering 2,028 hectares of tree cover lost in only the last five years – for perspective, the Aarey Milk Colony is spread over 1,300 hectares. On another note, this makes it imperative to construct maps of natural resources in our cities but, in terms of urban heat, the connection between such a large loss of tree cover – our cooling sink, as it were – and the rising heat is hard to miss. How can the MCAP speak of more natural cooling measures in a vacuum when the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation itself gives indiscriminate permission for cutting trees – the most natural cooling mechanism – to accommodate a range of construction activities?

In Mumbai, as much as in other cities, what’s called for is a focused but comprehensive heat action plan that takes into account the ground realities of how people live, work, and play – and what the local governments can do to keep them safe from heat-related illnesses or deaths. It’s simply the need of the season.

(The author is an independent journalist, columnist, urban chronicler, and media educator who writes on politics, cities, gender, and development. She tweets at @smrutibombay)