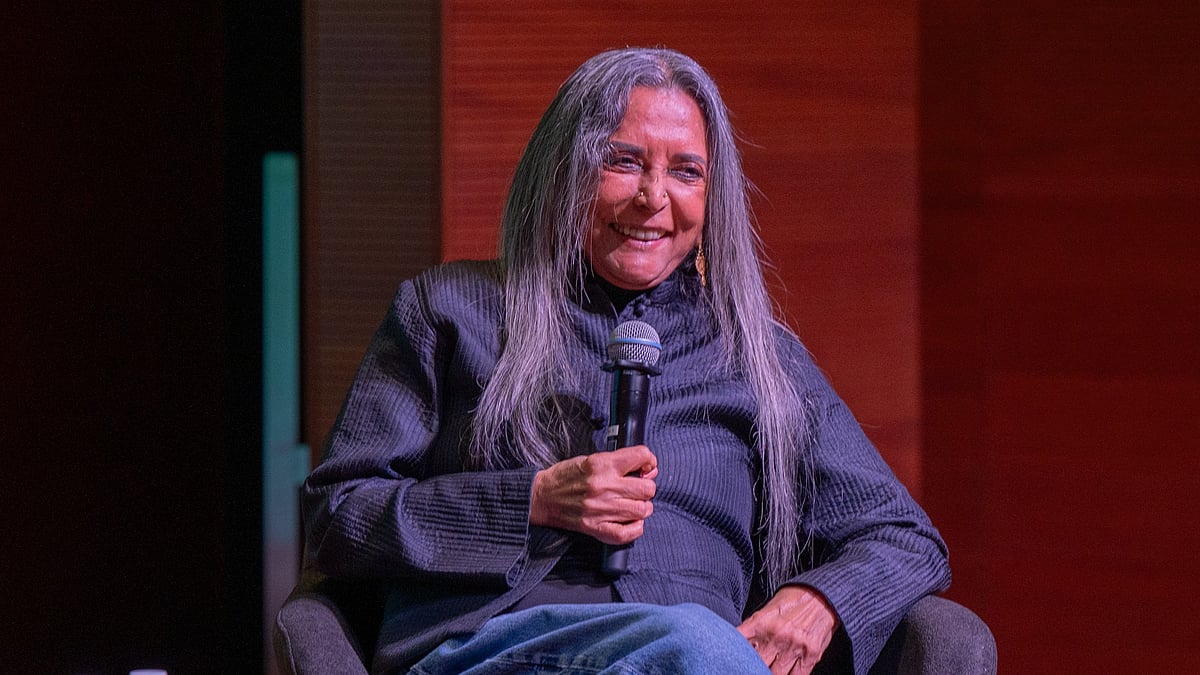

Of late, late, cinephiles around the world seem to have rediscovered the beauty and depth of Indo-Canadian filmmaker Deepa Mehta’s bold body of work. Last year, Mehta became the first woman to receive the Cinema Honorary Award at the 36th Singapore International Film Festival (SGIFF). It’s the highest accolade that recognises filmmakers who have made exceptional contributions to Asian cinema. The Free Press Journal caught up with Mehta in Singapore on the sidelines of the festival.

Excerpts from the interview:

You have been making films for around 35 years. When you see film festivals holding a retrospective of your films, like here at SGIFF, what feelings do they bring out in you?

Last April, they held a retrospective of my films at the Toronto International Film Festival. I hadn’t seen some of those films in a long time, like Midnight’s Children, or my favourite, Heaven on Earth. I was really surprised to see a young and diverse audience. I thought it would be mostly people of my generation and perhaps all white because since the ’90s, I’ve been used to mostly white people coming to see my films. I have never been to a screening of my own films in India because I don’t think they were ever screened. Fire was screened but they burned the theatres. Water wasn’t screened nor was Earth. So it was fabulous for me to see such an audience in Toronto, a multicultural city — or here in Singapore. The way my films have been embraced by Indians everywhere means a lot to me because I am Indian.

The empathy that you are able to evoke in your films, it seems to come largely from your interest in the “other”. So what about the other organically draws you to it?

I think it’s not that I’m drawn to it. I generally tackle subjects that I’m really curious about because I think they are unexplored and I want to know more. So it isn’t that I want to change anything or emerge as a savior. I made Heaven on Earth to explore what happens to working class immigrants in Canada who have a difficult time. I wanted to explore “female humanity”. What drove me was the curiosity about understanding how domestic violence is dealt with, if you are not in your own country.

Did you always have that innate curiosity or did you develop it?

My mother said that I was a real pain in the neck because I would always ask Kyun (why) for everything. I’ve always been curious. But as I grew older — and even to this age — I realized how little I know. That’s what drives my curiosity. It’s not that I’m attracted to the “other” (in a story). It’s my need to know more. That’s how and why I Am Sirat (2023) happened. When I started talking to Sirat Taneja, a lovely, young transgender woman, I was just listening to her intently. She comes from a working class family in old Delhi and lives with her conservative mother who was horrified upon learning that her son wanted to become a woman. I told her this story needs to be told. I co-directed it with Sirat.

When you work on films based on intense, complex subjects, what’s the inner dialogue that you go through? How do you contend with what to focus on and what to let go?

What really interests me is the journey of the film itself. When I begin that journey, it’s almost like a three-act script of setup, conflict, and resolution. While that arc of discovery is different for everyone, I’m interested in what I’m learning and what I’m curious about. How does it start? What are my characters made of and will they actually show me something?

Tell us about Forgiveness, the latest film you are working on.

We will start shooting Forgiveness in July. It’s based on Mark Sakamoto’s book and it deals with the WWII internment camps where the Japanese-Canadians, who were born in Canada and were Canadian citizens, were thrown into when the bomb fell in Pearl Harbor. On the other side, white people were put through hell as prisoners of war in Japan. So you have these two sets of atrocities. What’s fascinating to me is that for things that governments do, the people of the countries have to pay the price. Like, what’s happening in Palestine today is just unbelievable and yet it carries on.

Still from the movie Water |

You are often described as a transnational filmmaker. You explore themes related to various identities, cultures, and conflicts arising out of the clashes. How much has the world around you changed over the years?

Some things have changed for the better. The way women are treated and are responding, not just in India, but all over the world, has changed. I’m really happy with what’s happening with films in India. Be it Payal Kapadia with her film or Zoya Akhtar making mainstream Bollywood films with a different lens, the Indian women filmmakers are doing great. The change though has been slow. Also, self-censorship is really quite rampant in India right now, mainly for the big-budget films. But it’s heartening to see the emergence of Indian independent cinema.

What has making films on challenging subjects taught you?

My father was a film distributor and a theatre owner in Amritsar. So I grew up with films and not feeling that they were fantastic. I am grateful for the fact that I don’t hold films in awe. I think films are just as important as writing is or as expressing yourself in some way is. I have a very realistic approach.

Still from the movie Earth |

How then, as a realist, do you manage to make films that are visually striking with rich, layered imagery?

I guess that’s because I think in images. When I write, I write in images. I take about four weeks off before I can put on my director’s hat. But then, when I approach the script, I realize that I have actually written it in images. So it isn’t just the plot but it’s how the plot is expressed. What really got me interested in this was Natya Shastra, a fabulous ancient encyclopaedia on performing arts. It showed me how drama is expressed and played a huge role in how I write. When I finish a script, I always think — what are the colours of this film? For me, Fire was so much about India and its women. So the film is dominated by the three colours of our flag. Earth was about the partition and hence blood. So its colour palette was red with no blue in it whereas the colour palette of Water was blue with no red in it. For all my films, I always communicate the colour palette which helps the cinematographer figure out how to light the frames. It also helps the production design and the costume departments. Everyone then is thoughtful about what colours work and what emotions they represent.