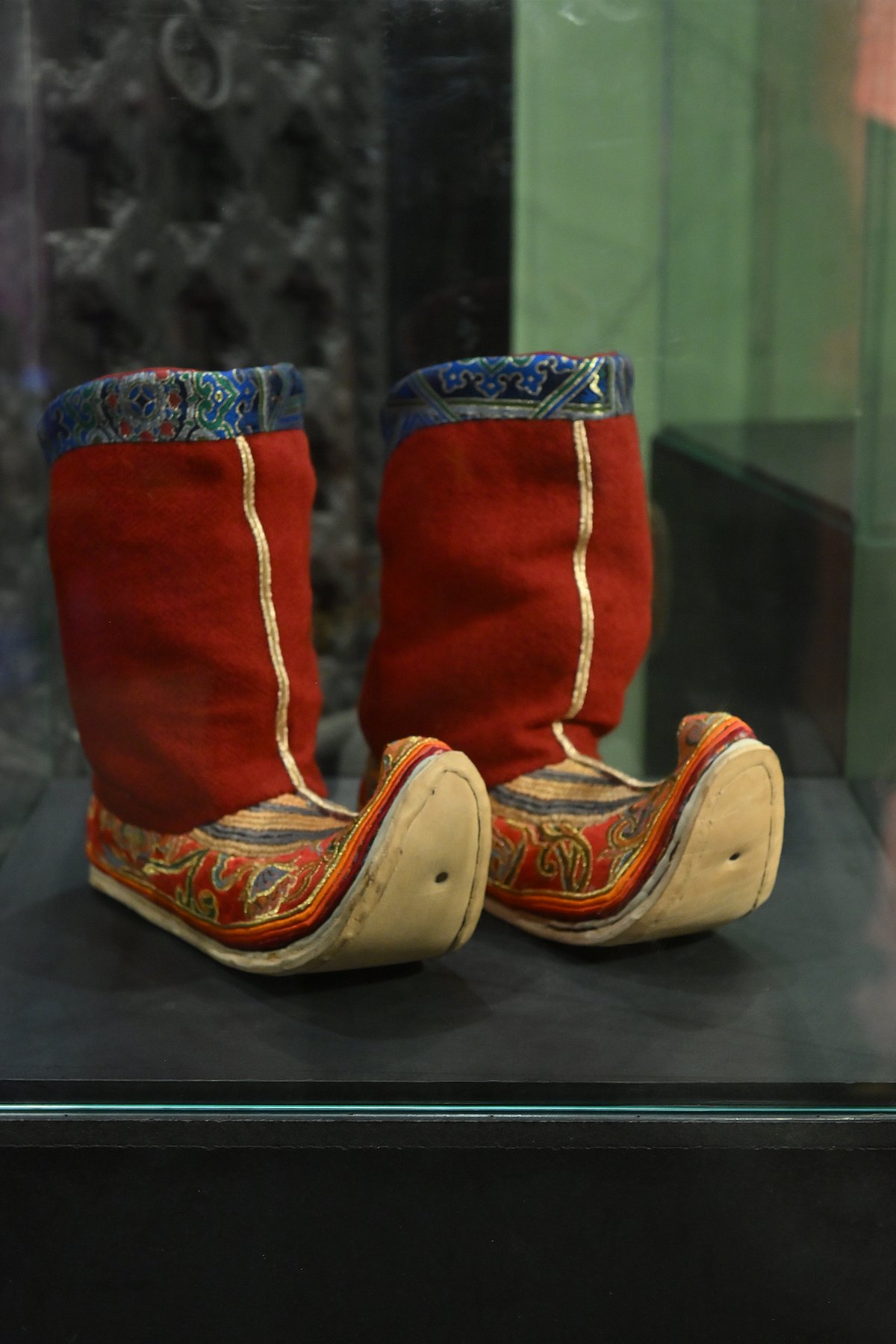

At the National Crafts Museum in New Delhi—thousands of kilometers away from high-altitude passes, prayer-flagged monasteries and the fierce winds of the Changthang plateau—Ladakh arrives without spectacle. In Between Wind and Wool: Ladakh Design Today, the region is revealed not as a picturesque backdrop but as a way of thinking, making and surviving.

This is Ladakh stripped of postcard romance, rendered through labor, memory and material — where textiles speak quietly of endurance, spirituality and women’s authorship. Curated by the Fashion Design Council of India, the exhibition resists the temptation to fossilize Ladakhi textiles as heritage artefacts. Instead, it presents them as living, evolving practices.

In a land where winter temperatures plunge below minus 20 degrees, pashmina has always meant survival before it ever signified luxury. Inaugurating the exhibition, Lieutenant Governor Kavinder Gupta described Ladakhi pashmina as a “unique natural gift” of the Changthang plateau, shaped by one of the harshest climates on earth. Luxury, the exhibition reminds us, is born here not from excess but from necessity and resilience.

What gives the exhibition its emotional depth is the designers’ intimate relationship with their material. Bringing together four women contemporary Ladakhi voices — Saldon; Jigmat Norbu and Jigmat Wangmo of Jigmat Couture; Padma Yangchan of Namza Couture; and Zilzom by Stanzin Palmo—the exhibition shows how ancestral techniques such as hand-spinning, weaving and resist dyeing are reimagined into modern silhouettes and sculptural forms. Ceremonial garments sit alongside ritual objects and experimental installations, underscoring how Ladakh’s design language has always negotiated the sacred and the functional.

Tradition as a living force

The sulma, the ceremonial robe traditionally worn by Ladakhi women, recurs throughout the exhibition in reworked avatars—layered, re-cut and re-contextualized—without losing its cultural gravity. “These are not garments meant to be sealed behind glass,” says Padma Yangchan of Namza Couture. “They are meant to be lived in, altered, passed on. If tradition doesn’t breathe, it dies.” At Jigmat Couture, Jigmat Norbu and Jigmat Wangmo translate monastic geometry and nomadic forms into contemporary ensembles that balance structure with restraint. “For us, pashmina is a living material,” Norbu explains. “It has survived because it adapts—just like Ladakh has always adapted to its environment.”

Stanzin Palmo of Zilzom brings perhaps the most intimate emotional register to the exhibition. Her work foregrounds the invisible labor of Ladakhi women—those who herd Changthangi goats, spin yarn and weave fabric in extreme conditions. “Women in Ladakh have always been designers,” she says. “They just were never given that name.” Meanwhile, Saldon introduces a conceptual edge, using experimental forms and installations to position Ladakhi textiles within global design conversations—without stripping them of context or meaning.

Adding a powerful visual layer are landscape portraits by Gautam Kalra and Hormis Anthony Tharakan, which place the garments against Ladakh’s vast skies, jagged mountains and elemental terrain. The clothes never overpower the land, nor does the land dwarf the clothes. Instead, Ladakh itself becomes the protagonist—wind-lashed, austere and uncompromising. The images reinforce the exhibition’s central argument: Ladakhi design cannot be separated from geography, climate or land.

Beyond aesthetics, the exhibition carries a strong social undercurrent. Ladakh’s textile economy is inseparable from women’s work and community knowledge systems. Gupta highlighted ongoing initiatives in skill development, quality control, branding and marketing—aimed at ensuring that craft remains a sustainable livelihood rather than a fragile legacy.

Open until March 2026, this is ultimately an exhibition about balance—between preservation and progress, hardship and beauty, isolation and visibility. It honors Ladakh without flattening it, allowing the region to emerge not merely as landscape but as a thinking, designing, future-facing culture.