The book under review brings to light the riveting story of two contrasting

personalities who would go on to define modern India

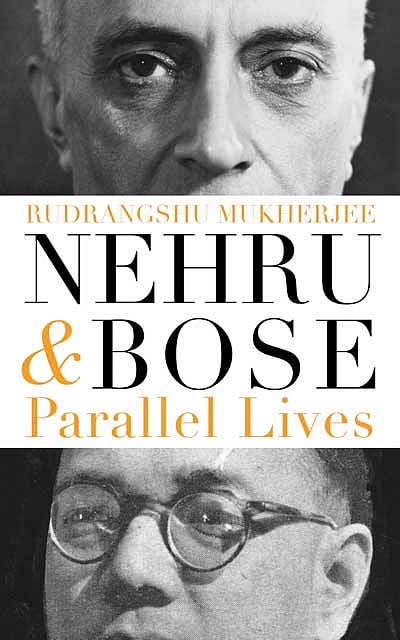

The author of this study on Nehru and Bose is Vice-Chancellor of Ashoka University and has taught history in several universities, Indian and foreign. He is the author of books on Indian history. The present book is a thoroughly researched and eloquent study of two principal actors, with charismatic personalities, who made history leading to India’s independence.

Nehru & Bose: Parallel Lives

Rudrangshu Mukherjee

Publisher: Penguin

Pages: 265; Price: Rs 599 |

It is remarkable how closely, on parallel lines, the lives of Jawaharlal Nehru and Subhash Chandra Bose moved; less than ten years separated them chronologically; both were born to relative affluence; both went to Cambridge; both gave up what could have been lucrative careers and joined the Indian national movement under the leadership of Mahatma Gandhi; both were aware of what was happening in Europe and in Asia, and their exposure to these developments radicalized their own ideas; both saw themselves as men of the left and were attracted to socialism.

Given the background, it was not surprising that they were drawn to each other. For a few years in the 1930s, they were close enough to be called friends—sharing views, reading similar books, and championing the same causes within the national movement. But by the late 1930s, the growing political distance between the two was obvious.

Their disagreements grew from their differing understanding of the course of the national movement, their attitudes towards Gandhi, and their views on fascism and from the very different mental landscapes they inhabited. By the 1940s, the friendship and affection were things of the past. But after Subhas’ sudden and untimely death, Nehru could not forget the bonds they shared and he revised his views about Bose and the Indian National Army.

Their relationship with Gandhi is also worth noting. Both respected and admired him; both saw him as the undisputed leader of the Indian people, but neither in their respective ways, was blind to his faults. But while Bose preferred publicly to air his differences with Gandhi and cast himself, often as his opponent.

Nehru’s dissent was more muted and therefore more angst-ridden. He found it difficult to break with Gandhi, even when he differed fundamentally and strongly with him. The nature of both their relationships with Gandhi was clear in the way they addressed him. For Bose, it was always Mahatma, respectful; for Nehru, it was invariably Bapu, personal, almost like a son to his father.

Both of them wrote books, one in exile and the other in prison. Bose wrote on contemporary India—“The Indian Struggle”, Nehru his “Autobiography”. Both began writing in 1934 and published their books in 1935. One book was strident, assertive and political; the other wistful, introspective and less certain of political orientations.

Bose died in mysterious circumstances somewhere outside India. No one still knows exactly where. Rumours had a field day. Many believe that he is still alive. It was rather different with Nehru. He went on to become prime minister in 1947 and stayed in that post till his death in 1964. His daughter created a dynasty from his political inheritance. Nehru’s name continues to entrance.

Sugata Bose, Subhas Chandra Bose’s grand-nephew and professor at Harvard, in his biography of Bose suggested that Gandhiji and Sardar Patel were political schemers fronting for big money and that Bose was the victim of their machinations. Mukherjee, concurs with the view that Gandhiji and his henchmen worked hard and plotted to ensure that Nehru and Bose did not gain control of Congress.

While Subhas was trying to sort out his differences with Gandhi, he wrote a long letter — twenty-seven typed pages — to Jawaharlal at the end of March. This missive is crucial for understanding how fast their relationship was deteriorating. In the first paragraph of this letter, Subhas wrote, “I find that for some time past you have developed tremendous dislike for me. I say this because I find that you take up enthusiastically every possible point against me; what could be said in my favour you ignore.”

It was Jawaharlal’s personal devotion to Gandhi that Subhas did not comprehend. Subhas did not allow any personal feelings to come between him and his aspiration to make his country free. He did not hesitate to leave behind his wife and his daughter in Europe knowing that he may not see them ever again. The personal was secondary to him: the political was paramount.

Thus, it was exasperating for Subhas to see again and again Jawaharlal differing with Gandhi but pulling back at the last moment from an open break. This made him lash out at Jawaharlal on occasion. Subhas believed that he and Jawaharlal could make history together. But Jawaharlal could not see his destiny without Gandhi. This was the limiting point of their relationship. This is a highly thought provoking book, extremely well-researched and written elegantly.

P.P. Ramachandran