The recent heated debate between political parties over the 150-year-old nationalist song Vande Mataram is a telling example of the growing disconnect between them and grassroots politics in the country. The hullabaloo raised by the BJP in Parliament, amplified by a compliant mainstream media on the eve of state assembly polls in West Bengal, is clearly linked to the ruling party’s bid to bolster its flagging Hindu nationalism plank there.

However, the fight between the BJP and the Opposition about the long-forgotten controversy over a few stanzas of the song is quite irrelevant to an overwhelming majority of people in West Bengal.

There is more than a touch of irony about the fuss created about Vande Mataram and literary stalwart Bankim Chandra Chatterjee as an electoral issue in a state where both the song and the writer have virtually no resonance except perhaps among five per cent of voters, mostly middle-aged and elderly college-educated upper-caste middle class Bengalis living in Kolkata and some major district towns.

It underlines the BJP’s desperate bid to scrape the barrel for an electoral issue that will strike a chord with the local populace to counter its antagonist Trinamool Congress’s persistent campaign to paint it as an outside, non-Bengali occupation force.

Quite apart from the BJP’s clumsy, fumbling attempts in Parliament to resurrect Chatterjee as a Hindu nationalist, the entire exercise seems quite pointless since even if it were to win the debate with the Opposition, it would make little difference to voters in West Bengal.

The bunkum (excuse the pun) nature of the poll issue becomes evident from the demography of the electorate in West Bengal. There is no interest whatsoever in Vande Mataram or Bankim Chatterjee among the backward castes, comprising the largest block of voters; the scheduled castes, the third highest among states; the Adivasis; and the sizeable Muslim community. Even among the narrow band of upper-caste Bengalis, the rural and urban poor as well as the young have little connection with a nationalist song and literary figure over one and a half centuries old.

Unfortunately, there is a widespread but completely unfounded impression that electoral politics in West Bengal, unlike other states across the country, is hardly influenced by the caste, community, and ethnic background of voters but by a unique Bengali identity and cultural pride.

This myth has largely been propagated by the complete dominance of all major parties across the political spectrum by leaders belonging to educated upper castes, mainly Brahmins, Kayasthas, and Vaidyas, known as the Bangali Bhadralok.

Since none of the backward and scheduled castes, Adivasis or Muslims, have either produced strong state-wide leaders or separate parties, the educated Bengali middle class, despite its small number, is given a vastly exaggerated importance both in political and media circles.

The fact is that whether it is the Mahishiya backward caste farmers in the Howrah-Hooghly-Midnapore belt of South Bengal or the Rajbanshis of North Bengal in the border areas of Cooch Behar, Jalpaiguri and Alipurduar or the Matua scheduled caste migrants from East Bengal spread over Nadia and 24 Parganas, and other Dalit groups, perhaps none have even heard of Bankim Chatterjee and his song. Nor have Adivasi Santhals, Oraons, and Mundas, mostly found in the forests of Junglemahal, and least of all the large Muslim community in Murshidabad and Malda.

For instance, the Mahishyas, who have strong local networks, are focused on farming issues besides benefits from backward caste reservations recently introduced by West Bengal Chief Minister Mamata Bannerjee, which are also important to Rajbanshis, who have been fighting for recognition and special welfare schemes, while the Matuas are worried about citizenship rights after migrating from East Bengal.

Other Dalit sub-castes, like the Bagdi and Malo agricultural labourers and fisherfolk, as well as Methor sweepers and Dom cremation workers, are overwhelmed by extreme poverty compounded by social discrimination even as Adivasis fight for forest rights and against marginalisation. As for Muslims, the only poll issue is sheer survival.

Interestingly, the BJP’s growth in West Bengal as the main opposition to a dominant Trinamool Congress since the 2019 Lok Sabha polls is not, as popularly believed, due to a surge of Hindutva across the state.

Despite latent anti-Muslim tendencies among the educated Bengali Hindu middle class, harking back to memories of horrific communal atrocities during the partition of Bengal many decades ago, there is very little evidence to suggest that the remarkable performance by the BJP in the national elections, running the Trinamool close, is because of Hindu nationalism. In fact, judging by the poor performance of the BJP in Kolkata, where the upper-caste Bengali is concentrated, the success of the saffron party lies elsewhere.

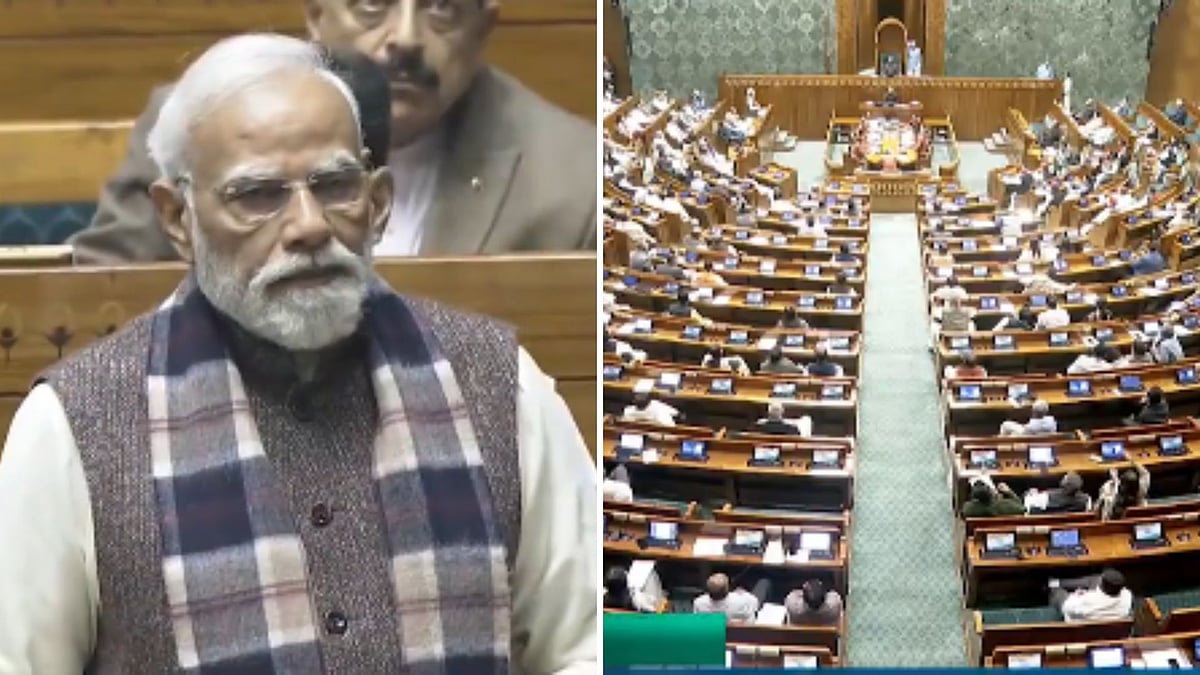

Indeed, it is the BJP’s ability to mobilise a section of the OBCs, Dalits, and Adivasis with the help of local RSS workers and with the promise of Prime Minister Narendra Modi delivering on their specific local demands that wiped out the previous Opposition Left and the Congress in West Bengal, forcing Mamata Bannerjee on the back foot.

However, despite engineering a series of defections of important Trinamool leaders, the BJP has struggled to oust the feisty West Bengal chief minister and lost momentum in the state after showing initial promise, as proved by two successive elections, the 2021 state assembly polls and last year’s Lok Sabha contest, when her party scored comprehensive victories.

Contrary to popular perception, Mamata Bannerjee has succeeded in keeping the BJP at bay not because of her greater appeal to Bengali cultural sensibilities over a party remote-controlled from outside.

Although she and her party leaders have lost no opportunity in debunking the BJP’s ludicrous bid to appropriate figures of the Bengal renaissance in its Hindu nationalist pantheon, the cunning chief minister has spent far more effort in introducing grassroots schemes to consolidate support among backward castes, Dalit communities, and Adivasis.

This is why the rhetorical bluster from both sides of the aisle in Parliament on Vande Mataram and Bankim Chatterjee is nothing more than a red herring disconnected from the electoral dynamics of West Bengal.

The writer is an author and senior journalist.