It is 2022, and in 2022 to believe that walls, of any kind, will keep you safe is, frankly, laughable. But try telling that to policymakers at the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI). I suppose belief comes with the territory (sic).

Let me contextualise, so my apologies in advance for a crash course in wall history.

The first instances of walls as defence or security go back to the 21st century BC to Sumerian rulers Shulgi and Shu-Sin.

The oldest walls found in existence so far are those of the temple of Gobekli Tepe in Urfa, southeast Turkey. Since then, walls have been built across all civilisations and almost all continents to much effect and admiration. Including the Indus Valley Civilisation.

Closer home we find them dotting the Aravalli ranges from Delhi to Jaipur and further south — long, winding walls populated by langurs and rose-ringed parakeets and the occasional temple or dargah. Walls that dominate an otherwise desolate landscape. We can find similar walls across the length and breadth of the subcontinent.

The great city of Delhi’s own affair with walls can be seen across its topography. A walk in the beautiful Sanjay Vann will have you admiring the colossal remains of Qila Rai Pithora round Mehrauli. As you trace your way down the lost streams from Mehrauli to the River Yamuna, you will find other old walls — at the Satpula and at Siri.

There are other fine examples, still, at the Hauz Khas Madarsa and Tomb, around the Qutub Golf Course, at the Tughlakhabad Fort, at Lal Kot and the Purana Qila, or Ferozshah Kotla. There are a lot more.

You cannot blame the people of Delhi for this faith in walls. Since the time of Shahjahan’s Shahjahanabad, and the glory of Chandni Chowk, the ramparts of the Red Fort have held sway on the city’s, and the country’s, imagination.

Impossible to ignore, they are an institution, even in modern-day independent India, so much so that even the present Prime Minister feels compelled to fall in line and make his Independence Day address from atop those walls.

Yes, they ooze pride, glamour, power, bravado, posturing, grandeur, royalty and colonialism. Looking at safety, though, is a slightly different thing. The last time a war was fought on Indian soil where fortifications helped saved the day was possibly sometime around the First War of Independence.

War, the largest human preoccupation in the contemporary world and, possibly, the largest spend of all national governments combined, has changed unrecognisably since. Force and front-facing confrontations are not the norm any more. Surprise, strategy, stealth and innovation have become synonymous with good war practices (the oxymoron is not lost on me there!). Similarly, defence has had to evolve — into surveillance.

Surprise, surprise! Both as an essential element of a successful attack and also as a wake-up call to the many babus who sit and sanction fences and walls — violence, its methods and its perpetrators have changed.

Crime has undergone similar evolution. Crime and violence are long past the wall in every sense of the word. And all our nostalgia will not keep them like they used to be in our grandparents’ time.

So, on this particular Monday in September, as I walked to the Mehrauli terminal of the Delhi Transport Corporation past Adam Khan’s tomb, I noticed a heavy steel fence being put up with tall, heavy gates. The fence sits on the outer wall of the podium around the octagonal Lodhi-style tomb. An inverted-T-shaped staircase leads up to this podium.

I ignored the catastrophic damage being done to its periphery wall to erect this ugliness and enquired from a security guard who was doing this and why.

As expected, the ASI — possibly the most ill-informed, archaic and intellectually rigid institution you could find across the globe that works in building conservation — was having this put up to protect the monument and for people’s safety so that unwanted people did not spend time there in the late hours. The ASI seems to have some strong religious beliefs that lead it to expect good human behaviour only between sunrise and sunset. And that places with heritage value should be locked through the hours of darkness to keep them free of sin and ungodly activity.

Does locking places make them safer? Does a curfew prevent crime? Do gates make colonies safer? Does locking parks keep women safe? Does putting steel fences and lockable gates (one of them permanently locked) on community spaces like Adam Khan’s tomb make the public spaces of the city safer?

Or are these carefully veiled, politically motivated actions? Are they demonstrations of ownership and power? Are these tools by which certain sections of society wield their privilege? Means by which to control and dictate the lives of the poor, the economically disfranchised.

The podium of Adam Khan’s tomb is a public space unlike any other. It is a gateway to Mehrauli. A rendezvous for friends in the evening, for women to sit on the steps and spend a few hours away from the stifling walls of their homes. A space for kids to learn roller skating and vendors to sell jhal-muri and papad to the thousands who pass through this place for a brief respite in their busy, stressful lives.

Is this the way of the upper class to drive home its privilege and economic status on the pavement walkers and hawkers of the city? How do we decide that fencing or sunset-to-sunrise curfews make things safer? These are patriarchal assumptions, put into practice to control and regulate the lives of women.

Our experience tells us that spaces with people are safer than places without people. Yes, places with people are safer than places without people.

Or is the city meant be safe... only for the rich?

Locks, fences, gates, walls keep people out. Mehrauli now has one less place to go to. One less place to be in. I have a fear this is a growing trend.

In an age of technology, surveillance, AI and the internet, why are we behaving like feudal lords devoid of intelligence?

There is no doubt in my mind these walls and fences will only go on to make the city unsafe for us lesser mortals... again!

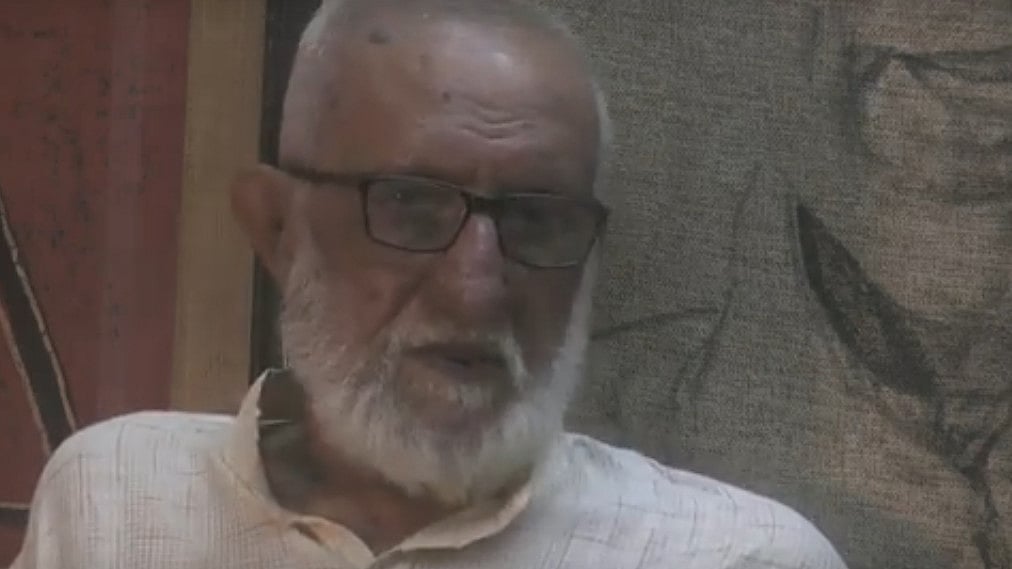

Henri Fanthome, an architect who trained at the SPA, lives and works out of Mehrauli, Delhi and writes about design and urban spaces