Sa Kaeo in eastern Thailand is famous for Khmer ruins and “Lalu”, spectacular canyon-like soil sculptures caused by ground subsidence. The province, a gateway to Cambodia, has been in the news for another reason.

As someone who has spent decades coping with Delhi’s infamously foul air, I was immediately drawn to a recent report in Bangkok newspapers about the Thai army and Sa Kaeo provincial administration coming together with Cambodian authorities to tackle air pollution, particularly PM2.5, in parts of the Thai-Cambodia border. Thai and Cambodian authorities plan to share information, run a campaign to reduce burning of waste in the open, and offer public health services to communities affected by smog in the border areas.

The major sources of PM2.5 — particles that are 2.5 micrometres or smaller in diameter and are highly injurious to health — at the Thai-Cambodia border are crop burning and forest fires. In the pipeline are joint efforts to patrol the borders to prevent illegal burning, wean farmers away from crop burning by increasing the value of leftovers from the harvest, and a public awareness campaign to educate border communities about the impact of PM2.5.

Anyone who is familiar with Southeast Asian history would know of the love-hate relationship that Thailand and Cambodia once had. The two countries even sparred at the International Court of Justice (ICJ), in the 1960s, over a long-disputed area near Cambodia’s 900-year-old Preah Vihear temple.

But in 2024, they are pitching for cross-border collaboration to tackle a common problem with serious health impacts.

Transborder haze is a perennial problem in Southeast Asia. The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), an intergovernmental organisation of 10 Southeast Asian countries, with an impressive record of promoting economic integration among members, now has an online haze portal and a coordination centre.

Everything is not perfect. Many experts flag gaps such as the lack of a uniform air quality index among member countries. But all said and done, they are taking steps towards building a collaborative haze response.

The question: if Thailand and Cambodia which have had a history of cross-border tensions can come together to tackle a common challenge, what prevents India and Pakistan from doing so? Why is playing the blame game the default response on an issue with such severe health impacts?

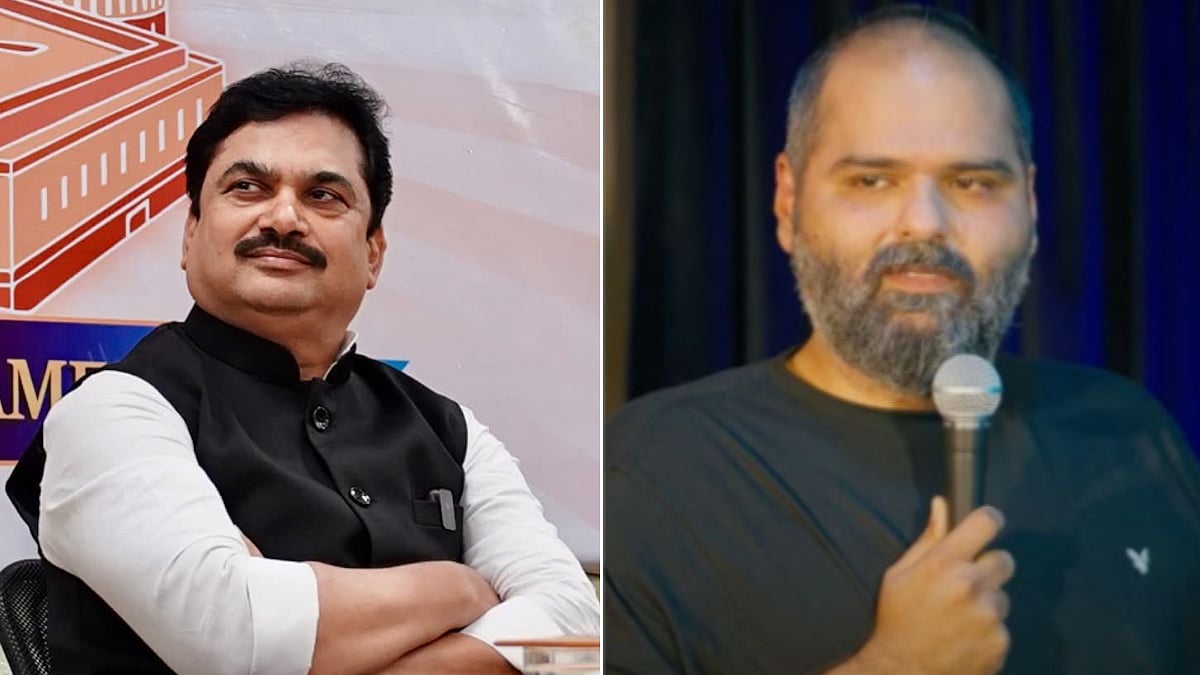

Even within India, the blame game is what makes news each time intensely polluted air shrouds the national capital. Last November, when the air quality index in parts of Delhi hit nearly 500, there was a familiar war of words between the Aam Aadmi Party-led Delhi government and BJP-ruled Haryana and Uttar Pradesh on who is guilty.

It is not just Delhi which chokes on polluted air. Indians living in many small towns and cities suffer too. Last year even Mumbai, with its proximity to the sea and relatively cleaner air, experienced one of its most polluted Octobers — the air quality index (AQI) reached over 300 in some parts of the city.

Other parts of the world battling air pollution are beginning to recognise that this constant blame game does not lead anywhere; that trans-border problems need trans-border solutions.

South Asia, a global hotspot of air pollution and home to 37 of the 40 most polluted cities in the world, with major metropolises such as Delhi, Lahore, Dhaka and Kathmandu at the top of the foul air league, is still to officially acknowledge this stark reality.

A united South Asia can beat air pollution, said a recent World Bank study. Titled ‘Striving for Clean Air: Air Pollution and Public Health in South Asia’, the report argued there are economically feasible, cost-effective solutions to achieve clean air in the region, but this requires countries to coordinate policies and investments.

Looking at the issue through an airshed approach could make a big difference. “South Asia has several (transboundary) airsheds — for example, Pakistan-India; India-Nepal; India-Bangladesh. Cross-border pollution becomes egregious during periods when farmers near borders engage in rice stubble burning. Collaboration could entail joint scientific research; understanding the flow and dynamics of regional pollution; data monitoring and sharing; installing data monitoring infrastructure at borders; and collaborative policy actions, like exchange of technology such as the happy seeder, or a cross-border pollution tax. Some examples of cross-country air pollution collaboration include US-Mexico, ASEAN countries, and the European Union,” said Sanval Nasim, assistant professor of economics, Colby College, USA, an expert on air pollution.

“Meeting the World Health Organisation’s guidelines on fine particulate matter (PM2.5) — the air pollutants posing the greatest health threat — would increase an average person’s life expectancy by almost seven years in Lahore, 10 years in Delhi, eight years in Dhaka and three years in Kathmandu,” Nasim wrote in a blog for East Asia Forum last April.

But as of now, there is not much of cross-border collaboration happening in South Asia on dealing with dirty air. There is a high trust deficit between India and Pakistan and that affects data sharing or any kind of serious collaboration. India’s National Clean Air Programme does not talk about collaboration between local or national governments.

“The Male Declaration and SACEP (South Asia Cooperative Environment Programme) provide for cross-country collaboration and knowledge sharing on the issue of transboundary air pollution but not much has been done through this initiative in the last several years. Restarting a knowledge sharing platform across South Asia would be a useful first step in acknowledging and addressing transboundary air pollution,” says Bhargav Krishna, environmental health and policy researcher, Sustainable Futures Collaborative.

What about state governments in India? “There isn’t really any experience of states collaborating with each other voluntarily on the issue of air pollution, with airsheds having emerged as a more recent topic of discussion. The Commission on Air Quality Management (CAQM) is currently the only forum where states are brought together around the same table to direct action across boundaries with a focus on air pollution in the National Capital Region. We are yet to see any significant impact with the CAQM issuing several directions over its 2.5-year life. But expectations are high since it is accorded significant powers in the Act of Parliament under which it was created,” added Krishna.

Another key problem Indian researchers face is access to reliable data including on local impacts of polluted air on health. That could serve as meaningful evidence for policy action.

The bottom line: No one said cross-country collaboration is easy. But if other countries with an acrimonious past can do it, why can’t we? Does South Asia value the lives of its people?

Patralekha Chatterjee is a writer and columnist who spends her time in South and Southeast Asia and looks at modern-day connections between the two adjacent regions. X: @Patralekha2011