The flurry of statements over Mumbai’s Saki Naka rape case, heinous and blood-curdling in its savagery, would make it seem as if Mumbai had become the rape capital of India. Parallels were drawn with the ‘Nirbhaya’ case in Delhi in December 2012, which had led to citizen protests and changes in criminal law on rape. This case was trending on social media as “Mumbai’s Nirbhaya”, ostensibly with generous help from India’s ruling party and its affiliates that have a thing for the Uddhav Thackeray-led government. The insidious politicisation of the case demands a closer scrutiny.

Gender safety: Tale of two cities

Even one rape is one too many in any city or state but it would be a stretch to tar Mumbai as a city of rampant crimes against women. In 2019 – it is appropriate to read data for the latest non-pandemic year – Mumbai reported about half the crimes against women – and half the rape cases – that Delhi had. The National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) data for the year showed a total of 6,519 crimes against Delhi’s 12,902; Mumbai was at third place in the country with 394 rape cases while Jaipur registered 517 and Delhi had 1,231. Mumbai Police data for last year showed a 30 per cent decline in crimes against women but it was a year of pandemic-related restrictions, including lockdowns.

The 2019 data tells its own tale of the two cities that are most frequently compared on gender safety. Anecdotal evidence backs this up too. Many of us know women who moved from Delhi to Mumbai and felt safer in the latter. The idea or action of using public transport or hailing a taxi alone late at night in Mumbai seems less daunting, fraught with fewer risks, to women who have lived and worked in both cities.

Safer streets

Mumbai’s mixed use of space, merging commercial with residential, has a lot to do with keeping streets relatively safe, as any urban planner would attest. Exclusive gated enclaves with high walls separating them from the nearest street makes streets less safe. There is a truckload of evidence that gender justice – which includes gender safety – is best baked into urban planning and design itself. Governments would do well to take this into account.

Yet, Mumbai registered the number of crimes against women that it did. In fact, such crimes spiked between 2013-14 and 2017-18, according to a white paper by advocacy group Praja two years ago. Its analysis showed that cases of rape had increased by 83 per cent and molestation by 95 per cent in those years. Mumbai Police and women’s groups had attributed this staggering rise to increased reporting due to heightened awareness in the post-Nirbhaya years.

Long way to go

Casual sexism, molestation, sexual harassment which the law still coyly terms “eve-teasing” are commonplace on Mumbai’s streets; they should not be. It is not possible for women to simply loiter on the streets or in public places without attracting undue male attention. So, while crimes against women may be half those in Delhi, Mumbai’s streets are not crime-free or completely safe – yet. There’s work to be done, measures to be put in place, and vigilance increased.

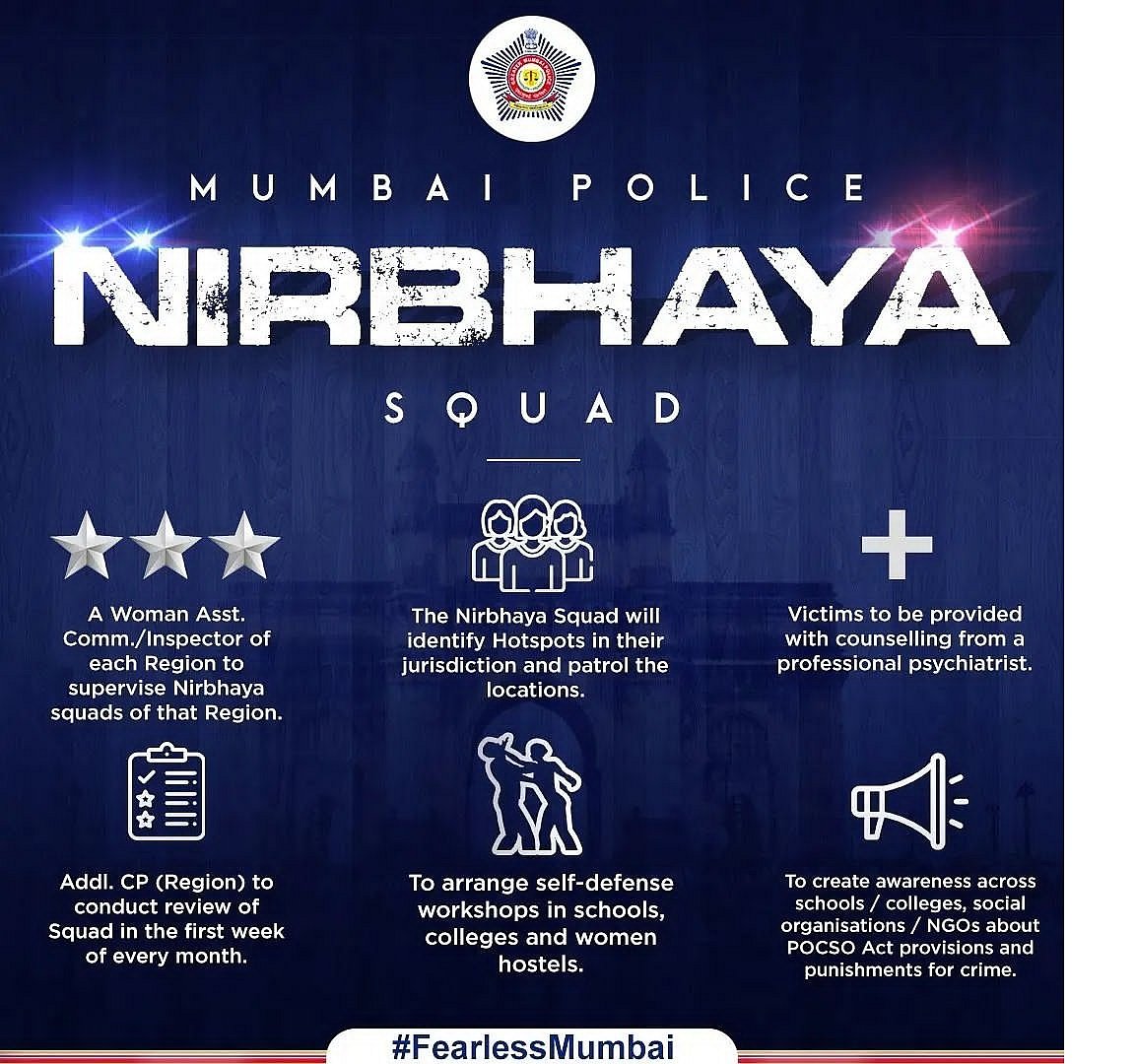

This is what the Maharashtra government and Mumbai Police pretended to do in the aftermath of the Saki Naka case. Given the sudden intense attention that it attracted from the opposition BJP, and coupled with the interest of the National Commission on Women, the Uddhav Thackeray-led government had to take visible action. The accused was arrested within a day, meetings were convened at the highest level, and a ‘Nirbhaya Squad’ was set up to patrol Mumbai’s streets. The first action is the due process of law; the case must be dealt with due urgency and justice swiftly delivered.

Old idea, new label

The Nirbhaya Squad needs a closer look. It may be well-intentioned but it is the classic case of an old idea with a new label. Its guidelines – every police station to have a women’s safety cell and mobile patrol vehicles, woman officers of ACP or PI rank, mobile squads on high-risk streets – have been well received but the squad will make a difference if it functions in the manner envisaged. Look no further than Nashik, where a similar squad called ‘Damini Pathak’ was rolled out on the International Women’s Day in 2016. It floundered only a week later when women beat marshals patrolling streets withdrew because they were not paid fuel allowance.

In any case, there are – should be – special cells in every police station across the city and the state. The idea of special cells located within each police station, comprising trained social workers and cops, to address all issues of violence against women goes way back to 1984 when Mumbai Police collaborated with the Tata Institute of Social Sciences for the project. The first special cell was set up in the police commissioner’s office and the model followed across all police stations. In 2005, the state department of women and child welfare began funding the cells and managed them jointly with the home department (that’s the police). The idea was eventually expanded to Thane and then to the rest of the state.

Women’s groups say these cells have yielded mixed results but they would rather have them than not. What’s unclear is how the new Nirbhaya Squad will work with the cells that are still functional, how the flow of work and responsibilities will be carved up and where the buck will stop. But the announcement has had immediate effect; the heat is off the Thackeray government and Mumbai Police.

Herein lies the challenge of ensuring gender safety – to keep relentless focus on the issue, to make existing systems more responsive and accountable, to push for fast and exemplary justice in every single case. The issue needs more, not less, attention across the board. This is easy to agree upon. What it does not need is the knee-jerk, episode-driven and ad hoc attention that it got in Mumbai in the wake of the Saki Naka case.

Smruti Koppikar, journalist, urban chronicler and media educator, writes on politics, cities, gender and development. She tweets @smrutibombay and surfs Insta on @bombayfiles