The high commissioner should have declared sympathy for poor Indians forced to toil abroad because of her government’s inadequacy

The recent riot in Singapore following the death of a young Tamil who was hit by a bus, and which led to the arrest of more than 30 Indian citizens, was a catastrophe waiting to happen. Even if not so acute, friction on race lines will persist so long as India continues to export manpower, whether tycoons who squander fortunes on ostentatious weddings, scholars who win Nobel Prizes, or unskilled labourers, who gratefully take on jobs that their hosts won’t deign to touch. Each of these cases is a testament to the mother country’s failure to give her children what they seek.

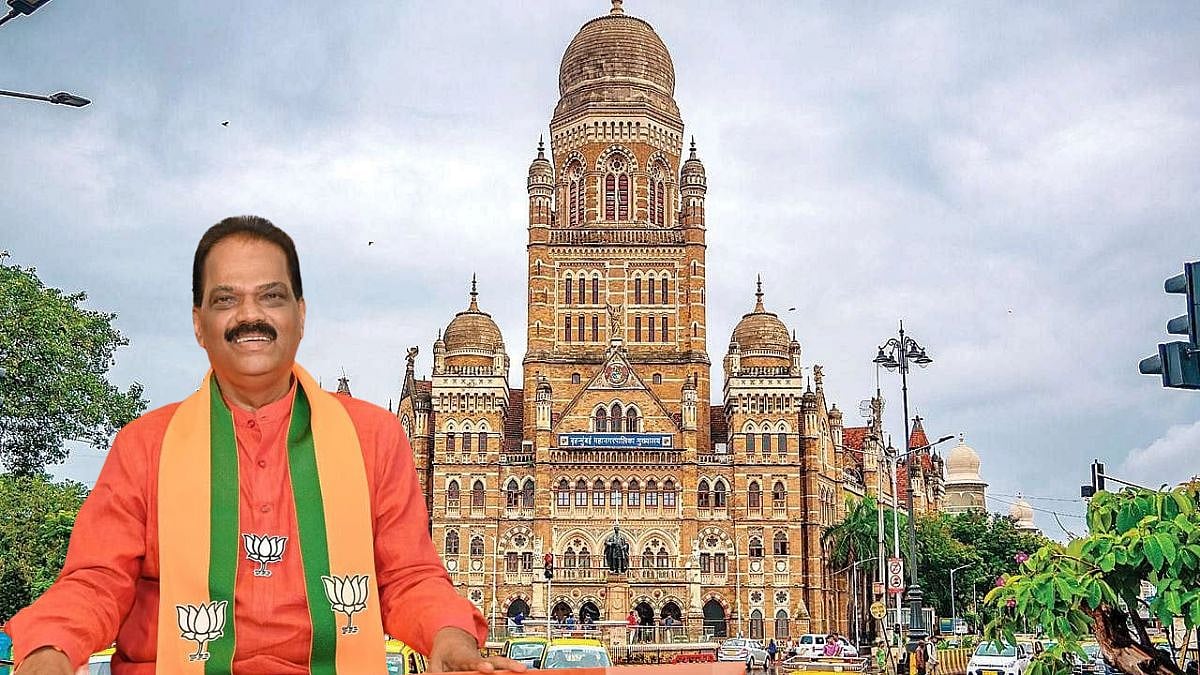

That is something India’s high commissioner to Singapore, Mrs Vijay Thakur Singh, should appreciate. She rightly announced that the furore would not affect bilateral relations. But she should also have declared her government’s sympathy for poor Indians who are forced to toil abroad because of her government’s inadequacy. I cannot imagine any Singapore diplomat sounding so unconcerned about this human tragedy.

Ironically, apart from some Malays, every Singaporean is an immigrant. But older immigrants resent newcomers. The official population target of 6.9 million by 2030 means more foreigners and mounting resentment against them. An early instance of tension I discovered when researching Looking East to Look West: Lee Kuan Yew’s Mission India was over a 1966 law, forbidding a citizen’s wife from returning to Singapore if she had lived abroad for five years. Invoking this regulation, the labour minister, Jek Yuen Thong, urged Singaporean Indians working at the British base, which was closing down, to leave for good. Their provident fund money would “go a long way . . . since their country of origin enjoys a lower standard of living than Singapore”, he said slightingly.

Indian diplomats claimed to have acquired around then a tape in which the veteran Singaporean leader, Lee Kuan Yew, ordered Indians who didn’t like his policies to pack their bags and go. “We make very good suitcases in Singapore,” he is supposed to have added.

But what the Straits Times called “the scent of the S’pore dollar” proved as irresistible then as it does now. Some 140 Indians were refused entry in 1985. Nearly 9,000 were arrested in 1986 and 1,750 sent back. Other governments responded with courage and dignity. While Thailand quickly repatriated nearly a thousand illegals with Prime Minister Chatichai Choonhavan fulminating that warships, instead of passenger ships should be sent to Singapore, India’s high commissioner pretended to know nothing of the arrests until Singapore officials released no fewer than 88 letters he had ignored. P V Narasimha Rao and Natwar Singh were outraged in 1989 when whipping overstayers was legalised, but successive Indian high commissioners seemed strangely indifferent to the plight of the poorest of their countrymen.

In 1992, a ruling People’s Action Party MP, Choo Wee Khiang, said in a speech in Parliament in Mandarin, “One evening, I drove to Little India and it was pitch dark but not because there was no light, but because there were too many Indians around.” Little India is one of Singapore’s less glittering districts where, as the name indicates, a large number of Indian shops, businesses and eating places are located. It is not a residential ghetto only because Lee introduced a system of mixing up the races in the low-cost government HDB (Housing Development Board) flats where more than 80 per cent of Singaporeans live.

But Little India is where Indian and Bangladeshi labourers gather on Sunday evenings – their only free time in the week – to meet friends, exchange news, change money and collect letters from home. The area is thick with South Asians and movement becomes very difficult. Additional Chinese Singaporean policemen are always on duty.

Publicly, everyone came down like a ton of bricks on Choo, who apologised for his derisive comment. But virulent Internet postings after the riot reveal another story. Many Chinese Singaporeans tacitly supported Choo’s demand for fewer Indian and Bangladeshi workers. Tan Cheng Bock, another PAP politician who complained of feeling “threatened” by increasing immigration, clearly touched a popular chord. He was re-elected by the largest margin in 2001.

Singapore’s race relations don’t permit easy analysis. The complexity extends beyond Chinese and Indians. There are sometimes strains between local and mainland Chinese. Expatriate Indian bankers and business executives, whom Shashi Tharoor called “Global Indians”, are not always in sympathy with local Indians, and vice versa. Malays comprise about 14 per cent of the population and feel discriminated against. Europeans and Americans (called Caucasians) are, of course, universally deferred to, especially by the colour-conscious Chinese. Yet, Indians can be found in positions of trust and authority. Lee argues strongly that there are many more Indians in the cabinet than their share of the population (about 6 per cent) warrants. In fact, a popular joke had a European dignitary wondering if he had taken the wrong flight and landed in India by mistake when President Devan Nair received him at Changi airport and presented the foreign minister, S Dhanabalan.

South Asian labourers on short-term contracts are at the bottom of the pecking order. Many of these Tamils and Telugus make enormous sacrifices (selling land and jewellery) to pay for the journey. A few among them are diploma-holding engineers who found it impossible to get a job in India. They live austerely to send back money, and are now worried that the Singapore government may stop issuing them visas and work permits. They build houses, sweep the streets, clean lavatories and do other menial work Singaporeans refuse to touch. Many Indian workers complain of being forced to compensate their employers for the levy on employing foreigners. Others accuse authority of turning a blind eye to illegals when major constructions have to be completed. The Indian high commission generally ignores them, travel agents and employers exploit them, and the locals look down on them. Only Lee’s iron discipline prevented institutionalised colour bar against these workers.

People react differently to discrimination. Some protest, others kowtow. I was shamed and embarrassed by another Indian, whose sycophancy prompted even the Chinese to joke he would have his nose flattened and eyes narrowed if such surgery were possible. Even he confessed that his Chinese neighbours in the low-cost government-built flats that house more than 80 per cent of Singaporeans held their noses when walking past him. Chinese find Indians smelly!

The milling crowds that provoked Choo’s ire have nowhere else to go. Some workers tried congregating on the ground floor patios of HDB houses — chatting, eating, drinking beer and playing cards — but flatowners roughly drove them away. “We built those flats!” a young Tamil foreman commented bitterly.

Executives from India and even local Indians might feel some backlash but Indian workers will bear the brunt. It won’t deter them, since Singapore pays so much more, even for menial work. But India will have to decide whether exporting labourers and maids is consistent with the national pride of an aspiring country.

SUNANDA K. DATTA-RAY