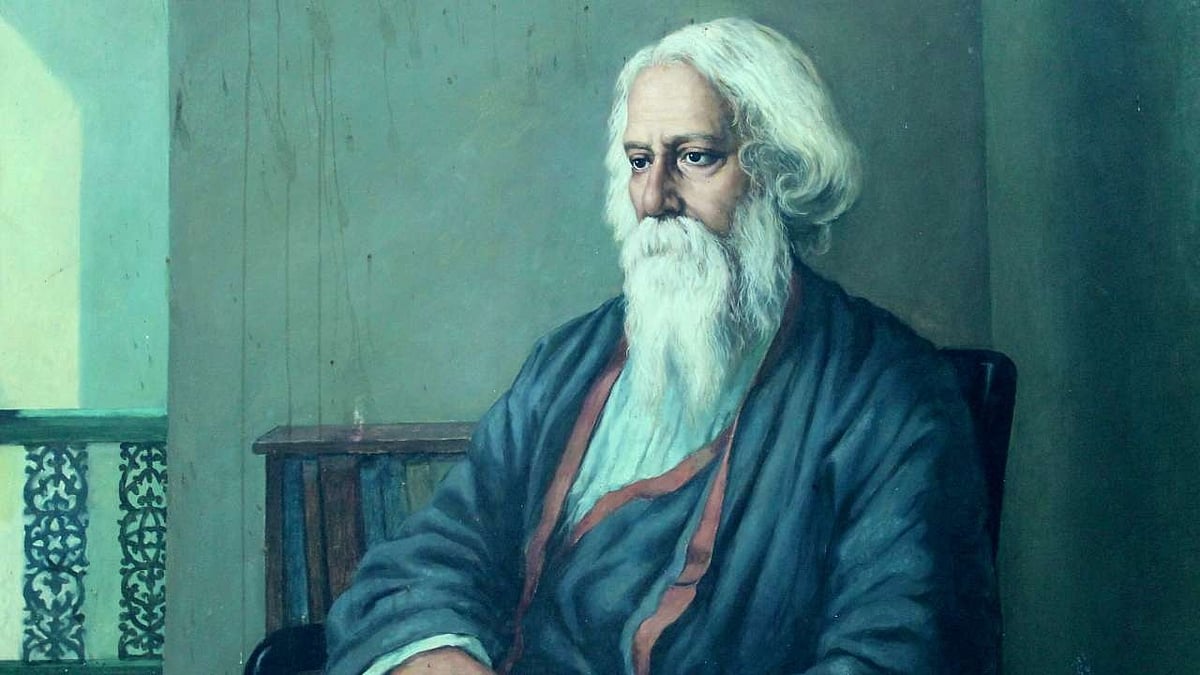

I'm able to love my god because he gives me freedom to deny him.

-Rabindranath Tagore

To me, god is formless, but divine effulgence.

-Rabindranath Tagore, 'Stray Birds'

May 7 is Rabindranath Tagore’s 160th birthday. A mystic poet and India’s first Nobel laureate in Literature way back in 1913, Tagore’s poetry and his literary works are still as relevant as they were, a hundred years ago. In fact, his relevance has increased manifold in these times of belligerent nationalism and extreme religiosity. Tagore would have been appalled to see the misinterpretation of nationalism and degeneration of religion. To him, country and religion were accidents of birth.

Hailing from the advanced Brahmo Samaj (Satyajit Ray also belonged to Brahmo Samaj), Tagore’s upbringing was non-religious and non-ritualistic. In other words, it was liberal and syncretic. Like Sufis, Tagore was non-denominational and non-sectarian. Nirad C Chaudhuri defined Tagore’s religious approach as a latitudinarian’s all-embracing religiosity and not a tartuffian’s sanctimonious piety.

Emphasis on spirituality

Being a mystic (rahasyavadi), Tagore’s emphasis was on spirituality. In this age of pathological religiosity, Tagore’s all-encompassing understanding of god and religion will help mankind, esp. Indians, become more human and humane because Tagore tellingly wrote, ‘Be a human to be humane and that is man’s ultimate self-realisation.’ What a profound definition of religion or spirituality! It defines religion or spirituality without articulating it. Tagore had a natural inclination for Persian mysticism, though he knew no Persian. His father Maharshi Debendranath Tagore was a scholar of Persian and would read Deewan-e-Hafiz and Ribatul Raada’tan-e-Mansoor Hallaj (Dying murmurs of Mansoor Hallaj) in original Persian. He’d recite the sublime verses from Hafiz and Mansoor's Deewan (oeuvre) for the young Rabindranath in his mellifluous voice and manner.

When the senior Tagore explained Mansoor’s dying murmur on the scaffold, Aztam-un baasit mee mazhab-o-khuda’reez; mee un vahid tabul-zeest (I’m beyond god and religion/I’m one with Him), the An-ul-Haq (I’m the Truth or Aham-Brahmasmi of Upanishad) got embossed on the mind of young Rabindranath and stayed with him till he breathed his last on August 7, 1941. Throughout his life, Tagore’s concern was to find out the basis of the religion that united human beings, and search for it in the truth of man’s nature. Tagore realised that teaching of religion can never be imparted in the form of lessons, but he found it in the living personality of man. In other words, Tagore’s religion was based on the divinisation of man and humanisation of god.

God in every human

While explaining the meaning of humanisation of god, he said ‘Humanisation of god does not merely mean that god is god of humanity but it also means that it is the god in every human being.’ Maanush ii ishwar/Ishwar ii maanush (Man is god and vice versa), was his spiritual refrain or dictum in life. Tagore told his Irish friend and poet William Butler Yeats that his Gitanjali (song offerings) was a eucharistic offering (Nirmalya) to the god that’s within every human and is immanent. The Upanishadic concept of Devam antarnihitam (god resides within) guided his life, not the outer or external manifestations of god and religion.

It’s interesting to note that Tagore’s first and original manuscript of Gitanjali and its 103 lyrical poems had the word God written in lower case, in lieu of the conventional upper case! Not that his knowledge of English grammar was inadequate. Tagore deliberately wrote god in a lower case to drive home the point that the divine consciousness is on an even keel with human consciousness! Imagine, such exalted thinking more than a century ago! But it was William Butler Yeats who changed Tagore’s god to God while editing the poems for publication. The atheists and evolved humans must be thankful to Tagore that because of his theo-lingual initiative decades ago, today, more than 150 leading publications across the world write god instead of God!

God-loving, not god-fearing

Neither did Tagore ever like the term god-fearing for the devout. It was always god-loving for him: god and fear cannot coexist; he wrote to his Argentine friend and disciple Victoria Ocampo. Love for humanity was Tagore’s raison d’etre. It was his paramount religion. Since he didn’t anthropomorphise god/s, his spirituality was inclined towards transcendental Agape (a Greco-Christian term referring to unconditional love, ‘the highest form of love, charity’ and ‘the love of god for man and of man for god’). In this age of religious supremacy, obduracy and sectarian conflicts, Tagore’s superlatively sacred views on god and religion can be of immense help.

And when it comes to his perceptions of nation and nationalism, Tagore believed that nation is an accident of birth. Like Albert Einstein, Tagore also believed that nationalism was the measles of mankind and a rather sophisticated form of primitive tribalism and troglodytism. “My love doesn’t end with the man-made boundaries of ‘your and my country’. It goes beyond that to encompass the whole mankind,” Tagore wrote to one of his British friends. He believed that one’s not an Indian or British. One happens to be an Indian or British. We don’t choose a country or nation. It happens to us. Tagore had a cosmopolitan outlook. He was a philosopher with a vision.

Nitesh Rai put Tagore’s nationalism in perspective: ‘Rabindranath Tagore is one such cosmopolitan philosopher whose idea of nationalism finds a distinct place in the whole debate about the very idea of nationalism. His idea of nationalism was never restricted to India only, instead, it had worldwide appeal. Tagore would never fit in the kind of discourse that is taking place in contemporary India in the name of nationalism often said and misquoted as ‘Hindu nationalism’. He was against the exclusionary features and self-aggrandising character which is often found in various discourses on nationalism. He found elements such as chauvinism, aggression, the feeling of others and false pride... very common in the ideas of nationalism and therefore, he vehemently discredited it. For Tagore, such features in nationalism were not in the interest of humanity at large. This is evident from his archetypal work, ‘Nationalism’.

However, if we look deep into the works and ideas of Tagore regarding nationalism, he considered it to be good as long as nationalism served the interests of the poor and deprived people. Thus, opposition of the British authority for the reason that they were causing inhuman exploitation and impoverishment of the country, he would gladly associate and love to be in the league of nationalists.” In fine, Tagore was an evolved human who went beyond the perceptions, precincts and pitfalls of god, religion, nationalism and parochialism. M K Gandhi, one of Tagore’s greatest admirers, summed it up so nicely when Tagore shuffled off the mortal coil eighty years ago: A universal soul merged into universal consciousness. Yes, Tagore was a universal soul with a universal consciousness.

The writer is a regular contributor to world’s premier publications and portals in several languages.