Government spokesmen have been crowing about the amazing measures that the government has introduced to ensure an economic revival. Last week, D Subbarao, former RBI governor, went on record stating that India’s recovery would be, at best, K shaped, not V shaped. And a closer examination shows pitfalls ahead.

Such views are also articulated in a brilliant lecture by Arvind Panagariya. Professor of Economics, SIPA, Columbia University, New York. He delivered this talk at the 36th Commencement Day Annual Lecture of the Export-Import Bank of India last month. This talk, on India’s Trade Policy: The Past, Present and Future, also confirmed such fears.

Panagariya provided a bird’s eye view of the changes in India’s trade policy right from the days since this country’s independence. He pointed out how the first prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru was convinced that no country could become a great nation without investing in heavy industry. Steel, pharmaceuticals, space, and other core sectors were those that he was keen on promoting. The trouble was that all of them were capital intensive (Russia helped India, even while western nations refused to help India in areas ranging from milk pasteurisation, pharmaceuticals, steel, and defence).

Nehru’s vision, and Indira Gandhi’s follies

To ensure that scare capital was not frittered away, capital controls were introduced, and that in turn put restraints on imports as well. India’s external trade was therefore marked by meagre exports and limited imports.

Indira Gandhi took it a step further to control industry (and even banking) for political reasons. Industrial licensing was made more rigorous. Sectors like banking got nationalised.

The excuse given out for bank nationalisation – was that rural folk had to be catered to – was clearly a lie from the way Syndicate Bank was nationalised. Here was a bank which was headquartered in the rural area, with most depositors coming from rural sectors as well. It was more relevant to rural needs – with its pigmy deposits of just 25 paise.

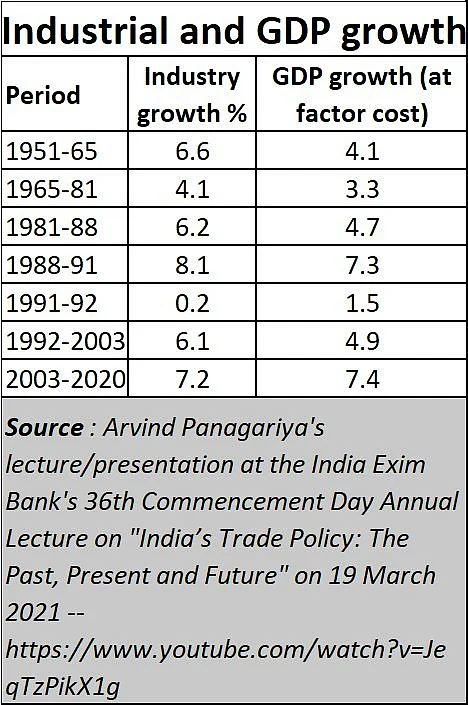

The nationalisation of Syndicate Bank confirmed that the real reason was to control access to funds by industry. Each industrialist now had to kowtow to the political establishment before he (or she) could be permitted funds, licences for production and even income tax exemptions. All this constrained industry and the economy remained stunted. GDP and industry growth collapsed (see chart).

The breath of fresh air came in the 1990s when liberalisation threw away licensing restraints for most sectors of the economy. Both GDP and industry growth revived.

As Panagariya put it, the Nehru model of self-sufficiency and import restraint – was destined to fail.

In the end, the objective of self-sufficiency which required rapid diversification of production structure proved fatal to growth and poverty alleviation aspirations of Indian policymakers.

There was an inherent conflict between the rapid achievement of self-sufficiency and productive efficiency. It is baffling that the policymakers failed to see this obvious contradiction not only in the 1950s but also during the subsequent two to three decades.

Panagariya explains how the Nehru focus on heavy industry led to creating a separate structure for low capital and high employment industries which were then called cottage industries – like apparel, footwear, furniture, and numerous other light manufactures. That later became the small-scale sector. To protect them new laws were created reserving items for this sector, with a cap on labour and investment. Hence the entire sector was designed to remain dwarfed.

Tariff and trade

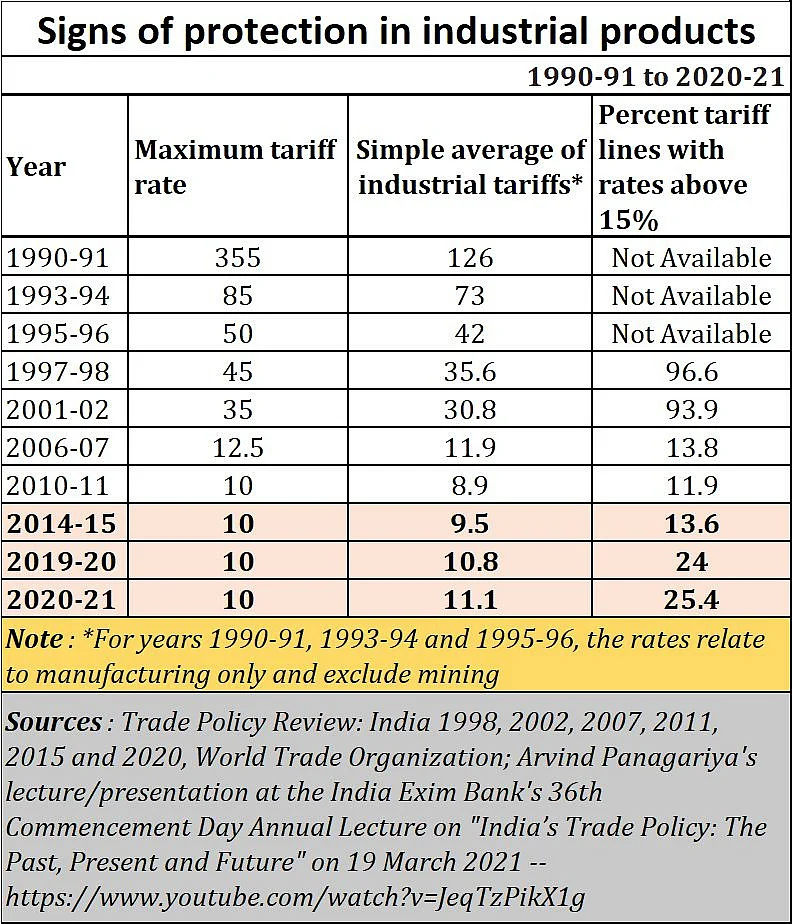

With imports blocked, small scale sector products reserved for low capital enterprises, it was not surprising that protection went further and introduced import tariffs as high as 355%. Gradually, post the 1991 liberalisation, policymakers began loosening their grip on imports. Tariffs began climbing down. This continued till 2010.

Thereafter, even though the maximum tariff rate remained at 10%, the simple average of industrial tariffs began climbing – from 8.9% in 2010-11 to 11.1% in 2020-21.

Similarly, the number of items with rates above 15% also began climbing.

Thus, protectionism has begun rearing its head once again.

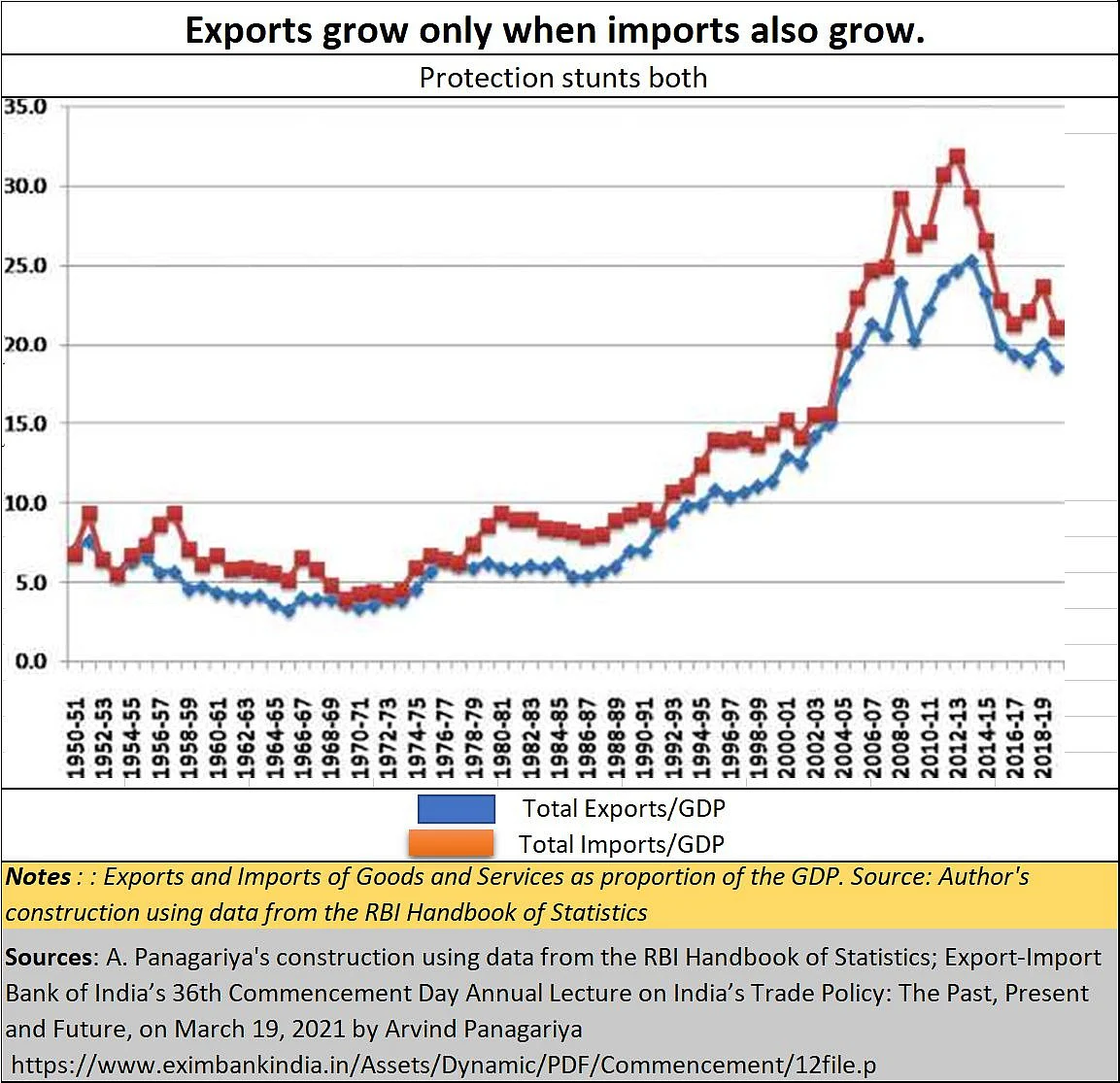

The result was a clampdown on imports. That in turn impacted exports as well (see chart). Post 2014, imports declined, and so did exports.

Now if India wants to increase its exports, it will have to loosen its grip on import tariffs. Imports will rise, but so will exports.

Of course, there will be howls of protest from the makers of solar panels and other products. But these cries are the same as were heard in 1990 when the then prime minister Narasimha Rao and his finance minister Manmohan Singh (who later became prime minister) just ignored them. If India had to join the big league, it would have to be with greater participation in global trade. That, explains Panagariya, will not happen till imports are also allowed because easy imports allow for easier exports.

Anti-dumping roadblocks

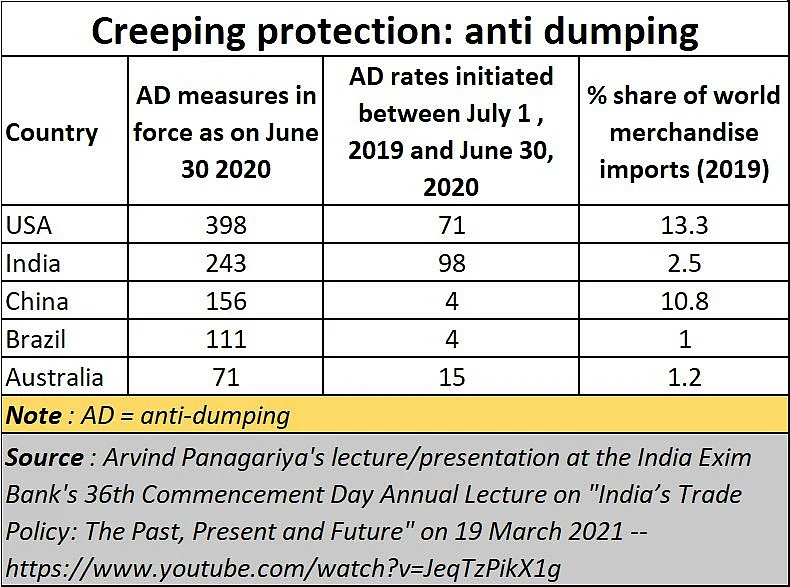

That India has tried to discourage imports can be seen from the steady rise in import tariffs and in the pugnacious way it has gone into trade disputes. Consider how India had as many as 243 anti-dumping (AD) measures in place as of June 2020. The only country that had a higher number of measures was the US. Yet when taken against the trade volume, the US is significantly bigger, with a 13% share in global merchandise imports, compared to 2.5% for India. All other countries, including China, had fewer anti-dumping measures in place.

Moreover, look at the anti-dumping rates initiated between July 1, 2019 to June 30, 2020. India had the dubious distinction of slapping the highest tariffs of 98% against 71% for the US and significantly lower levels for almost all developing and developed countries.

The PLI problem

It is in the context of such moves that Panagariya is also uncomfortable with measures like the Production Linked Incentives (PLI). This scheme has been hailed by big industry, but Panagariya warns that it is another sign of creeping protectionism.

Panagariya admits that when compared to import tariffs, PLI is preferable. But PLI does create a bias towards high investment and will bring in investments that are not really of global scale. “The scheme favours… capital intensive sectors,” says he. That will mean fewer incremental jobs as well. And by focussing on select sectors, it ignores other low capital, highly labour-intensive projects that could also have immense export potential. When governments try to channelise capital flows, they go against market wisdom. They even distort markets and the ingenuity of entrepreneurs.

The capital bias is evident in the PLI scheme for large scale electronics announced by MEITY or the ministry for electronics and information technology. As the Meity announcement states, “The scheme shall extend an incentive of 4% to 6% on incremental sales (over base year) of goods manufactured in India and covered under target segments, to eligible companies, for a period of five (5) years subsequent to the base year as defined.” The PLI is for high volume, invariably capital intensive, and low employment industries. That may not be the best way to revive India’s industry.

For instance, leather exports-based industries do not find any mention under the PLI schemes. Does this have something to do with the aversion that the government harbours towards cattle slaughter. In fact, even economists like Swaminathan S A Aiyar have argued against the PLI scheme.

If yes, that will be going against the one of the most competitive industries in the world. Ditto for scores of small engineering units which also exports a bit here and a bit there because of their ability to produce customised products that their customers require, and which large manufacturers would not be interested in because they are low volume opportunities.

India has thus tried to bring about protectionism and a command-control economy through PLI. That could distort India’s strategic strengths on the one hand and make India a high-cost economy once again on the other. Both would end up shrivelling India’s share of global trade.

Unless remedial measures are taken promptly, India could actually end up losing both market share, and the prospects of rapid economic revival.

The author is consulting editor with FPJ.