After a country has been hit by a pandemic, how should people spend money?

In India the patterns that are discernible are quite weird, as a survey by a media house indicates. In the absence of a good healthcare system in India, the focus is to fortify yourself. That could explain why there is a surging demand for immuno-boosters like chyawanprash (a cooked mixture containing honey, sugar, ghee, herbs, and spices) and other proprietary concoctions. Sales have gone by 283% in June, while the brand leader, Dabur, has reported a 700% surge in sales.

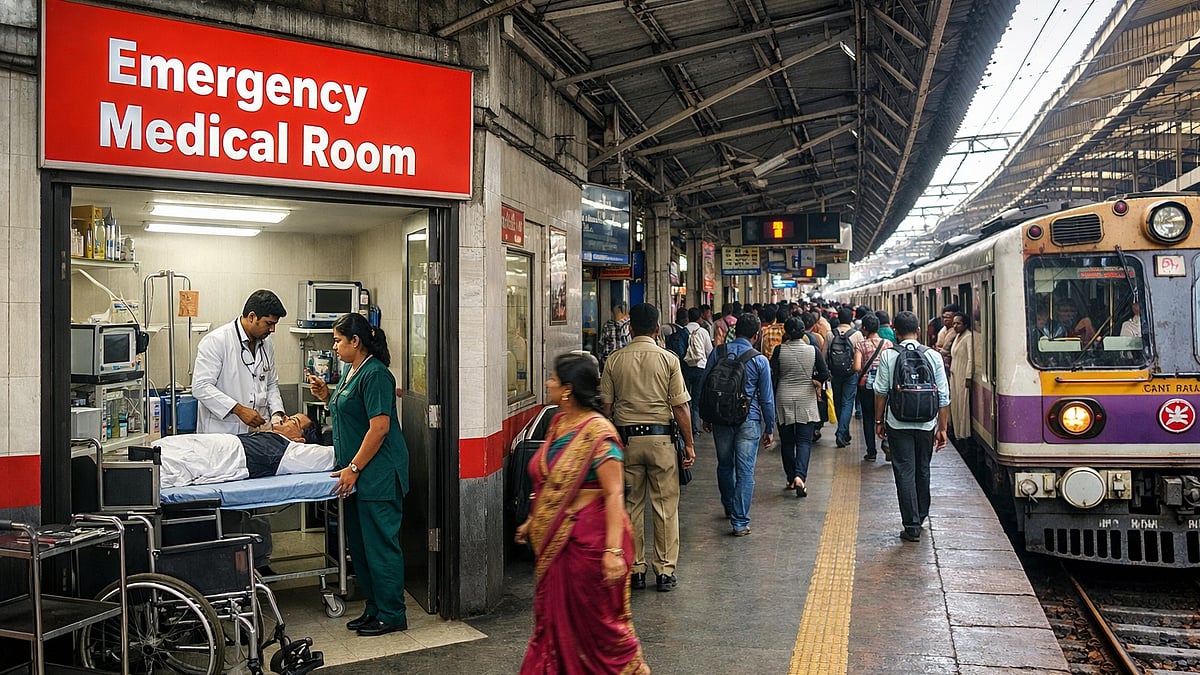

Expect the cost on medicare to go up as well in India. This is because few would like to go to ill-equipped, not-so-sanitary government hospitals. It may be worth pointing out that some of the most prominent politicians, when afflicted by Covid-19, opted to be treated at private clinics rather than India’s premier (government-owned) AIIMS.

This is a far cry from a country like China, where the quality of medicare – funded largely by the government – is almost universal. Hence the spending is more on sports and gymnasiums, on food and beverages and on education. The last is interesting, because China already has in place an incredibly good educational infrastructure for primary and secondary education.

The increased spending on education, therefore, would be on courses which equip children for higher studies. In China, unlike as in India, higher education is meant primarily for the academically competent. The focus is squarely on merit.

The Chinese are preparing themselves for a brave new world -- far more aggressively than India is. They are getting prepared for a more competitive world. This is a far cry from India, where the clamour for banning examinations and diluting syllabi for studies is not unusual.

But in one respect, China and India are similar. Spending on food and beverages has soared, while expenditure on fine dining in restaurants has plunged. Not surprisingly, in India, sales of products like Maggi Noodles, chocolates and biscuits have begun climbing. The distribution of biscuits by NGOs to desperate migrants as a nutrition supplement also added to this demand.

In some ways, India too spends on education – especially on digital services. But it is not clear whether this is for entertainment and recreation or on education.

The lack of vision for education is visible in the much-touted New Education Policy (NEP). The policy has made some good recommendations. It has brought pre-school education into the purview of formal education. This will have two key benefits. First, it will allow for mid-day meals for children aged 3-5 years. These years are crucial for mental growth. Absence of nutrition can maim these malnourished children for life. Second, it brings an unorganised and unregulated facility into the mainstream.

But the NEP ignores the most important aspect of education – the teacher. It refuses to categorically state that teachers must be selected only on the basis of merit. And that they should be promoted based on outcomes. The failure to do this made India score disastrously at the PISA and the QS. ASER findings have shown that almost half the Std V children can’t read books meant for Std II – in any language.

Unless the teacher is paid more – so that the best talent moves towards teaching -- and unless outcomes are measured and the best performers rewarded, any tinkering with the framework of education (10+2+3 has now become 5+3+3+ 4) will become mere tokenism. The NEP does not talk about the disgraceful practices in granting grace marks to prop up the number of students who successfully clear examinations. But more on the NEP later.

The consequences of this absence of focus on both health and education are quite obvious. India’s rankings on the HDI (Human Development Index) and the HCI (Human Capital Index) are there for everyone to see. All of India’s neighbours have fared better than India (except for Pakistan). Thus, what was to have been a demographic dividend will end up impoverishing India.

As one studies the chart above, the contrast between India and China becomes all the sharper. China is looking forward to a future where its people can be in charge of industrial production, quantum computing and artificial intelligence. India’s purchase strategies are more a reaction to existing or anticipated conditions. They are defensive. They lack the vision that any country with a booming young population should have. Purchase options still revolve around essentials, not on things that could make Indians more competitive in global markets.

India has a lot of cleaning up to do if it wants to truly aspirational or even atma nirbhar.

The author is consulting editor with FPJ