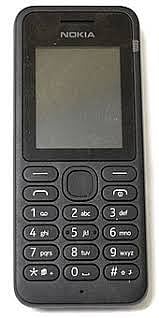

Nokia was once the leader of the world in mobile phone handsets. Its

largest manufacturing plant was located in Sriperumbudur in India as

part of a special economic zone. In a six-year period, it produced more

than 500 million handsets, much of them exported. Nokia employed a

workforce of more than 30,000, including indirect employment, and it

had a big share of women employees. It was indeed the rockstar

example of what it meant to make India a manufacturing hub for the

world. It stood for a high-quality product and the high-quality employment of a global brand, adding to the then brand of ‘Made in India’. But much before ‘Make-in-India’ became a slogan, the Nokia plant was shut down. It has now become a case study in business schools, of the opposite of a

Cinderella story, of how a successful, dream-like story can go kaput.

This is not the place to discuss the demise of the Indian factory in

all its gory details. A part of the blame goes to the excessive zeal shown by

India’s tax authorities, bordering on tax terrorism, and also broken

promises. Blame must also be apportioned to Nokia’s own failure to anticipate the global revolution in smart phones and getting stuck with a large-scale capacity in low-cost feature phones. In hindsight, it can be safely said that much of this woeful story was avoidable and an alternate

glorious future could have been written for Nokia, as well as India’s

prowess in mobile phone manufacturing for the global market.

More importantly, what have we learnt from the Nokia story? Stories of

the excessive zeal of the taxman continue. Despite lowering the corporate

tax rate to East Asian levels and down to 15 per cent for new manufacturing facilities, the mindset is still extractive. India’s tax regime, including the GST system, is still burdensome and inhibits competitiveness. We have been successful in attracting Apple to make its iconic phones in India, so that is something to be celebrated. But as compared to the scale of annual production of a 100 million phones achieved by Nokia, Apple is tiny.

The Apple story was successful thanks to an approach called the ‘production linked incentive scheme’, which gives incentives related to volumes. That has been extended to 13 sectors, including mobile phones, drugs, battery cells, man-made textiles, auto components and solar panels. The total budgeted outgo on incentives is nearly Rs 2 trillion over the next five years. The PLI scheme seems to be supported by protection via import tariffs.

This is an old school economics textbook approach that to attract

investment in the country, you raise tariff walls. Hence, a foreign

player can access India’s vast consumer market only by jumping across

that wall, that is, being forced to invest in India. This is not the

lesson which Nokia or Sriperumbudur taught us. That plant came to India

not by jumping tariff walls, but by being attracted to low-cost labour

and skills, as well as to the ease of doing business in an SEZ. If we promote

domestic production by raising import tariffs, it increases costs for

the domestic buyer significantly. It also acts like an export tax, for

entrepreneurs who are using imported components to re-export their

products.

Unfortunately, India reversed its two-and-a-half-decade old

progress in tariff reduction in 2018. Since then, India’s average

import tariff on industrial products has gone up from 13 per cent to 18

per cent and has been applied to nearly one-third to one-half of all

10,000 odd product lines. Remember, high import duties increase

domestic costs and are a de facto export tax as well. Additionally,

the PLI scheme’s approach is to pick winners and champions. In some

sectors, this makes sense.

For instance, India’s import dependence on China for advanced pharmaceutical intermediates is 68 per cent and that

needs to go down. It is also a strategic sector, since it is in

healthcare. But India’s status as a leading bulk drugs exporter to the

west is also dependent on import of APIs from China. So, while PLI for

APIs is good, it will take some time to wean away from China

dependence. But in general, the government cannot, and should not be

in the business of choosing winners and champions, and least of all,

future trends in technology. Imagine if the government had a PLI

scheme for Nokia to produce low cost 2G phones in very large

quantities, it would have been stuck to paying for an obsolete

technology and if it abruptly discontinued it, then it would have

been guilty of breaking a sovereign promise.

Such are the perils of incentivising production in fast technology industrial fields. Another hazard of PLI is that the government may specify too many details and try to micro-manage. This may be due to bureaucratic approach, or excessive caution in preventing abuse of government subsidies. One example of this overkill is that the bid document for the auto sector for those who wish to apply for PLIs is 187 pages long! Imagine the compliance cost. No wonder that so far, not many big players have stepped in, either for auto or for pharma. Thus, industrial policy which is too intrusive, too prescriptive, too keen to pick and choose winners, and

far too based on protectionism is bound to get tangled and not

succeed.

The recent case of the BSNL is illustrative. Forced to break away

from a confirmed tender to Chinese suppliers for its 4G network, it

found that the new bidders were 89 per cent more expensive and had no proven track record in producing at scale. Another anomaly is in solar

panels, where on the one hand, we want to achieve 100 gigawatt solar

capacity but have put tariff barriers on foreign suppliers. This will

increase the cost of domestic production of solar power. It is

inevitable that with too many conditions, India’s industrial policy will

become incoherent and inconsistent. The best approach is that which

gives private and foreign investors stability, predictability and continuity in a broad policy stance. Leave out the micro specifications if you want to succeed.

The writer is an economist and Senior Fellow, Takshashila Institution

The Billion Press