I was once a rebellious young architect; I would now use the nuanced “subvertive” to describe the undercurrents of my work. But back then, at 25, a year out of college, a friend and I had this wild idea for a New Capital for post colonial India. Back then we could never have imagined there would be an opportunity to see that wild dream realised!

Our idea involved wiping out all of Lutyens’ Delhi and building what we called a “People’s Capital” in place of the elitist gardens that are home to Delhi’s rich and powerful.

We imagined high-rises, walking avenues, parks and gardens, bicycles — a festival of democracy and freedom and equality. No cars. No classist elitism, and politicians who were loved by the people and did not need the proverbial seven rings of security to keep themselves alive.

It was innocent and childlike, but it came from a place of imagination and dreaming — a place of hope and excitement, a wish for the best world we could think of! That is what architects and designers do (mostly) — dream and work for a better world for everyone.

Architecture has always given hope and meaning. And there is no wonder it has been used since the beginning of civilisation to express and impress and define identities of people, cities, countries and governments. It was and remains an exercise of great significance.

In the 1990s when newly unified Germany needed a new Parliament building, a design competition was floated that was won by the celebrated practice of Foster and Partners, headed by (now) Sir Norman Foster to design what’s still regarded as on of the icons of modern-day Germany, a building architecture buffs travel from all continents to see.

Closer home in the 1970s, when East Pakistan was liberated, and a new capital complex needed to be built, Bangladesh looked to three of the most celebrated architects of the time — Le Corbusier, Alvar Aalto and Louis Kahn to deliver the goods. The task finally fell into the able hands of Kahn, who designed the Sher-E-Bangla Nagar in Dhaka, arguably the master’s best works. Completed in 1984, the complex and the spectacular Jatiya Sangsad Bhaban, its centrepiece, draw throngs of design aficionados to it in an architectural pilgrimage.

Also in the 1990s in Scotland, an international competition was held to design and build the new Scottish Parliament. It was won by the hugely admired Enric Miralles, an architect of considerable imagination and skill and someone I have looked up to since my formative years. The short description of the building on the Scottish Parliament’s website reads thus: “ The branch-shaped design has references to Scottish architectural history and was created to mirror the landscape. The design echoes the founding principles of the Scottish Parliament itself — openness, accessibility, sharing power and equal opportunity.”

Each of these buildings is a legacy, They are icons in their own right, and edifices that stand for a country’s identity. Whole nations look to these buildings as symbols of hope and inspiration, as beacons to the future. Architects across the globe acknowledge and hold them dear for their contribution to the world of design. They are national milestones in the truest sense of the word.

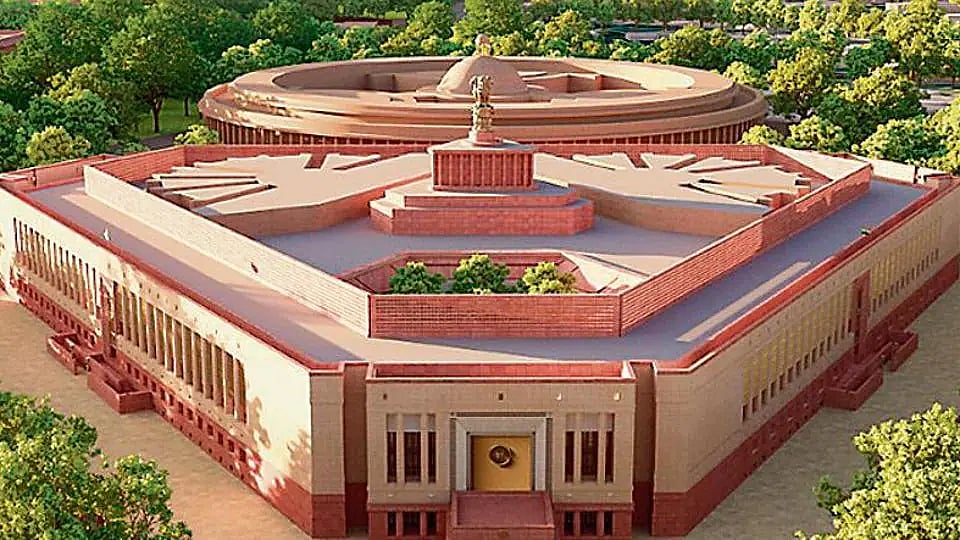

When the first images of the new Parliament were made public,my first reaction was, “What’s new?” It looked like a Lutyens building on a triangular plot. But aside from that, I couldn’t make out what the noise was all about. That it is now part of the most expensive road-renaming exercise in human history only adds to its un-remarkableness. A second look, and one confirmed that it was a decidedly bad Lutyens building, that it took about a 100 years to come up with this bad a copy was quite amusing. It looked like something the Chief Engineer of the Public Works Department would draft without help from an architect of any reasonable calibre.

A few months ago this new Parliament building was inaugurated — no mention of the architect, or the grand exercise in building a seat for governance befitting a 21st-century, almost-superpower, India. A picture of the Prime Minister, as has become the norm, in front of its entry portal was plastered across the pages of every national daily. And what I remember so vividly is the shoddy black paint over the cast concrete around the entranceway — possibly the worst casting job I have ever seen in my whole life, definitely a lot worse than the castings by untrained hands on my small building sites in far-off villages. And the unimaginative jali patterns that looked like they had been picked off an online catalogue and copy-pasted. Absolutely nothing about the picture was memorable except the feeling of being quite unquestionably let down.

Let down, not as an individual. No. As architects we are bound to have different tastes, and notions of acceptability, aesthetics, and interpretations. But as architects we all have exceptions, and especially of a project as significant as a new Parliament building in 2022 — that’s where this hits, hard and low!

It is not every day you get to design a new Parliament for the Republic of India. No sir, by the looks of its happens once in every 100 years, and that might be overestimating! This is the seat of the elected government — from where governance spreads across the states, to districts, to wards and finally to 1.4 billion breathing individuals that make India. And THAT is exactly where the let-down hits.

In a globalised world, 100 years after the last Parliament was designed, there’s been a Corbusier, and a Kahn in the subcontinent! Elsewhere’s there has been the Burj -Al-Arab, for crying out loud, and even an Antilia. Whatever their architectural merit, you cannot dismiss them.

And then we have the new Parliament — a bad replica of 100-year-old architecture that has been outlived. There is nothing remarkable about the new building — you look at it, and nothing makes you go wow, or even bring a twinkle to the eye. It just sits there.

The Harmika and Umbrella symbols abstracted from Buddhist Stupas, that hark back to Lutyens’ Rashtrapati Bhavan, sit most awkwardly on its roof and only underline the lack of architectural intent — almost caricature-esque. As if no one knew what to do with a flat expanse of terrace.

The whole assembly made me think of the pink cherry on top of of the found-everywhere pineapple pastry — a messy mix of oversweet yellow syrup, preserved pineapple, sponge cake and cream, with one cherry making it special.

Here was an opportunity any architect would die for. A chance to reinvent, redefine and present the country with a building that would not only stand the test of time, but hold a light and be a beacon for the future. That should have been entrusted to master of the craft and a true visionary.

Among the architectural greats of this country we have Riba Gold Medalists, Pritzker Winners, IIA Gold Medalists for lifetime achievements in architecture, who have flown the flag of Indian architecture on a global scale to wide acclaim, giving us buildings that the world admires and establishing an international recondition of architecture that is uniquely Indian and of the subcontinent and its people.

Sadly that never happened and we got what we got. Indian architecture could have triumphed, but sadly not this time.

This time Indian architecture lost — to a pastry.

Henri Fanthome, an architect who trained at the SPA, lives and works out of Mehrauli, Delhi and writes about design and urban spaces