I had written a long justification for a sequel, but have decided to can it and cut to the chase without fussiness, and a hope that you read the previous column on pastries.

What we have been witness to is not just bad architecture; that is, as the doctors would say, a system. There is a deeper underlying disease, and that is what we will talk about. There is a bit of history to this sort of thing – the idea that the state (or the ruling dispensation) knows better or will decide what should be built.

In the early 2000s, an open Architectural Design competition was floated for the Ministry of External Affairs Office, on the intersection of Rajpath and Janpath, a plot south of the Central Vista, directly opposite the National Museum. I think I was still in college, or just out; I remember viewing the competition entry by the very renowned Christopher Charles Benninger, from the Pune-based practice CCBA.

The history of architectural design competitions must be appreciated to have a better understanding of why this is important. Across the world, architectural competitions have transformed and defined eras. Competitions have brought to the fore little known and obscure architects, and given the world buildings that have become landmarks, not just for nations but have become symbols for generations. Some of these architects have gone on to become era-defining architectural powerhouses.

Architecture competitions are not a new thing, and you will be surprised how many of the world’s great edifices that we still marvel at came to be through competitions.

As far back as 1834, the New Houses of Parliament in London, by the architect Charles Barry.

Much more well known and Iconic, the Sydney Opera House, by Jorn Utzon. You cannot think of Australia without this beauty flashing before your eyes. And then there is this, that definitely divides the architecture and design community, but draws admiration regardless and is visited by millions each year – the Centre Pompidou in France. It singlehandedly brought Sir Richard Roger and Renzo Piano into the international limelight. These are a handful of the most notable.

We don’t remember the architects now, or how these buildings came to be. But there is absolutely no question about their value as buildings and how they have defined the cities and national identities they are now an inseparable part of.

Let us go back to 2000s Delhi and Benninger’s MEA Competition entry. The scheme was ahead of its time by decades, and I would argue that as the cause of its premature demise!

Unlike Lutyens’ weighted, stoic, century-old Indo-Saracenic style, Benninger’s building was contemporary in its language. It responded to its context, of Luyten’s Delhi, like an abstract artist painting, an extension of the angular geometries. It used scale, space and syntax rather than image and massing as its medium, which, I can only imagine, completely confused the powers that be!

The building had none of the blockiness, the darker red sandstone podium, the tall colonnades, and chhajjas, or the domes and chhatris, that have for a century been the markers of the power-centre of the country.

The many conversations I have had in the last week threw up some very interesting ancedotes that possibly were the last nail in the coffin for Benninger’s work.

The competition was open – no guidelines of style, vocabulary, building material or context. Architects were left free to imagine and interpret and design a modern new office for the Ministry of External Affairs at a landmark location in Lutyens’ Delhi. The competition was judged by a jury of eminent architects that selected the winner. It is still unclear if the results were made public. What is known is that the contract was never awarded.

The NDA was at the Centre then, and it is also rumoured that a certain influential minister looked at the selected scheme and commented: “We cannot build this, it is not Indo-Saracenic.” And that was, possibly, that! It never got built.

At the site now stands the Jawaharlal Nehru Bhavan, a sad, poor man’s imitation of Lutyens’ architecture. That seems completely lost and ill at ease, both from its lack of material and building detail and from a less than adequate understanding of architectural intent and design. (This description, of course, could be applied to its much later cousin, the new Parliament building, as well.)

As I look back now, in the aftermath of the new Parliament building, and reflect on the External Affairs Ministry office, one gets a sense that change is unwelcome and uncomfortable. Something that the establishment intrinsically resists – and that does make sense, in a self-preserving, self-serving and retaining-control sort of way.

But is it the right message for a nation – one that possibly has the largest population of young people in the world? A nation full of energy, hope and aspirations? What is the nation’s message to its youth?

I feel Benninger’s work was asking a very important question – not just about the architecture of the state, but a far more poignant question of us, one that the nation has answered over the decades since then. Also the fundamental questions on artistic expression, architecture and ethics – does our establishment honour and respect artistic expression and originality? Or is my best friend’s child or cousin going to be given the contract because he is my best friend’s child or cousin?

If a carefully appointed jury, in all its wisdom and understanding, selects a winner, is a minister with an ordinary degree – or worse – at liberty to brush it aside because it does not meet their norms of taste or limited understanding?

There are other questions too – of inclusivity, progress, acceptance (pardon my being poetic here). Questions that need asking for architecture (and governments) to stay relevant in the 21st century.

So the much larger and bigger question that presents itself is, are we looking for change? Are new orders and new futures welcome? And the answer, quite simply, is No!

PS: As an architect, practicing in the country and trying to run a credible practice which does meaningful work that is of value, it is not a nice answer to know.

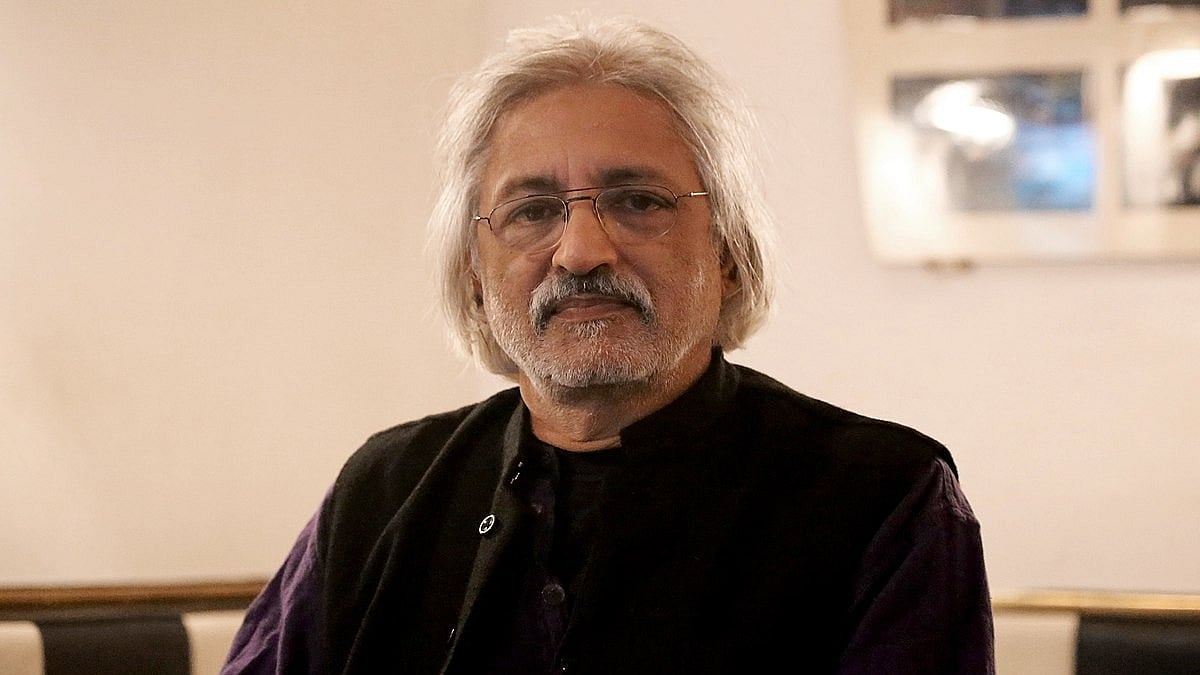

Henri Fanthome, an architect who trained at the SPA, lives and works out of Mehrauli, Delhi and writes about design and urban spaces