The five masked men raided the house close to midnight as the family was preparing to celebrate the 18th birthday of the eldest son. The men were armed with Little ArmaLites, AR18 5.56mm rifles.

They tied the mother and children to chairs and gagged them. The 42-year-old father was taken away at gunpoint. The family was told he will be returned within the hour.

Outside, the masked men drove the father some distance. Then they switched vehicles. They chained him, hands to the steering wheel and feet to the pedals, in the driver’s seat of a van. He was instructed to drive straight into an army post at the border.

The van was packed with a 1000 pounds of gelignite, a ‘jelly’ explosive invented by Alfred Nobel. The father was told that unless he did so his wife and children would be killed. It was either his life or his family’s.

At 3.55 in the early hours, the van was detonated by remote control. Soldiers Stephen Burrows, Stephen Beacham, Paul Worrel, Scott Vincent and David Sweeney of the 5 King’s Regiment Regular Army at Coshquin were blown to bits.

Patsy Gillespie was identified through forensics of a “piece of flesh attached to a bit of a zip of grey cardigan, and they found it on the roof of a bar over the border”. The bar was the Three Flowers Pub. It was October 24, 1990. The place was on the border of the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland, on the Buncrana Road between Derry/Londonderry and Donegal.

The professor who drove me down Buncrana Road on the first day as a scholarship student at the Institute of Conflict Research (INCORE), Magee College, University of Ulster, wanted to illustrate how borders could be open. A single black marble plaque near a bridge marked the border and the spot where Patsy Gillespie and his van were blown up.

Patsy Gillespie was turned into a human bomb, more than a decade before passenger aircraft were aimed at the twin towers in New York. Some say that he was the first human – or proxy – bomb used by the Provisional Irish Republican Army (Provos). He was not a volunteer but was ‘collateral’.

With little re-imagination it is possible to envisage his fate tied to that of 22-year-old Adil Ahmed Dar, the bomber of the convoy of February 14, 2019. The suicide attack that killed the 40 policemen at Lethpora in Pulwama district is now being re-analysed after then Governor Satyapal Malik’s interviews in which he quotes Modi has having told him “tum abhi chup raho”, you be quiet now.

Comparisons between Northern Ireland and Kashmir are facile. Yet they have parallels. The partition of Ireland means there are two Irelands – the Republic in the south of the island and Ulster in the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, like there are two Kashmirs, two Punjabs and two Bengals. ‘The Troubles’ in Northern Ireland lasted 30 years from the late 1960s killing some 3700 people. In Kashmir, they have lasted decades longer claiming multiples of that number in lives. Yet, the depths of tragedy are comparable because of the magnitudes – for a population of 1.7 million in Northern Ireland and that of 14 million thereabouts in Kashmir.

This month marks 25 years since the Good Friday Agreement of 1998, the settlement in Belfast that formally opened the institutions of a reformed police service, justice and reconciliation in Northern Ireland. A whole generation has grown up knowing only peace where once blood on the streets was routine. The erstwhile Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) was disbanded, the army returned to the barracks, and the ‘paramilitaries’ (as the armed militia of the antagonistic Republicans and Loyalists are called) accepted the idea of “rust in peace” by de-commissioning firearms.

It is far from a perfect peace, with Brexit stoking cries for independence in Northern Ireland, but it is a reminder that like war, peace must be waged.

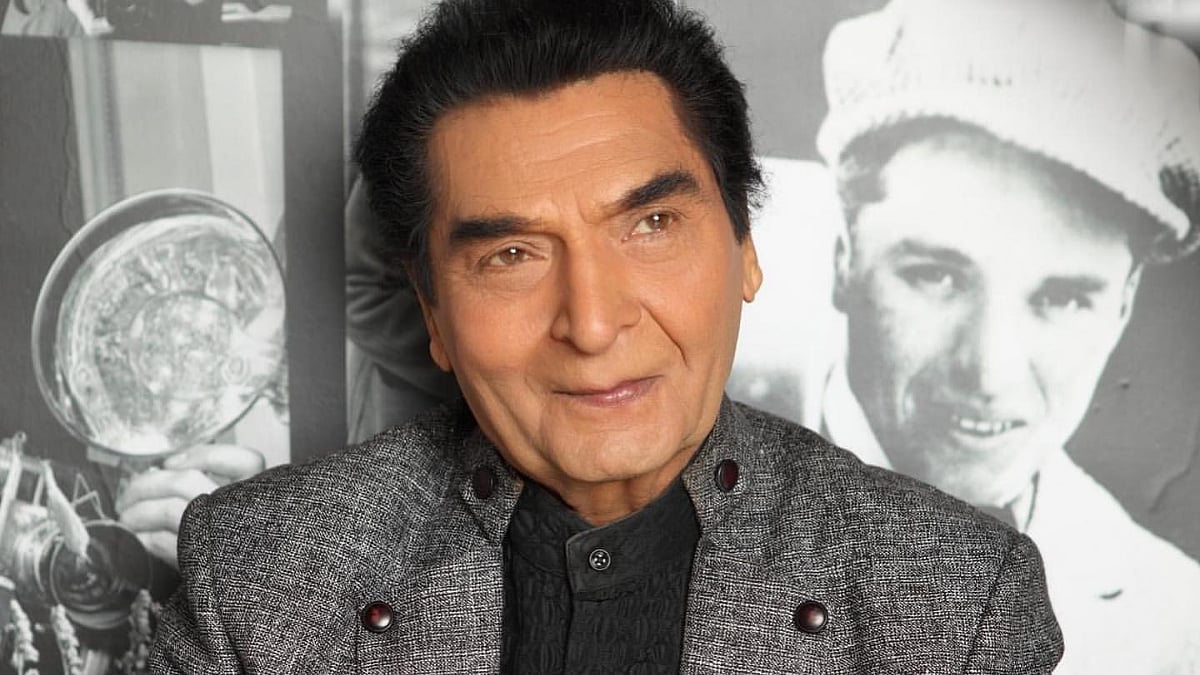

On the eve of one St Patrick’s Day in blustery Belfast’s Falls Road office of the Sinn Fein in 2004, the party’s leader Gerry Adams told me in an interview:

“The politics of condemnation, of heaping scorn on them (those who had taken up arms), of marginalising them, censoring them, of vilifying them, of describing them as terrorists, of pushing them to the margins, had not worked. So what did work (in crafting the Good Friday Agreement) was finding an alternative way to bring about the conditions for peace and justice.”

“We cannot ignore the histories of colonialism,” Gerry Adams told me when I asked him about parallels with Kashmir.

“I think the governments have big roles to play, because, in our situation – and you will have to translate how this fits into the situation in Kashmir – people were using armed struggle because they felt they had no alternative way.”

Back in Derry, the good professor explained that peace was a product of talks with all, “a deal struck in smoky bars and sleazy pubs”.

You be quiet now, tum abhi chup raho, isn’t there.

Sujan Dutta is a journalist based in Delhi. He tweets from @reportersujan