Power tariffs are a worrisome topic for state policy makers, corporate accountants, entrepreneurs and economists. They burden common consumers. The beneficiaries are agriculturists and economically weaker sections who get subsidized power. But power supplied to them gets stolen. Transmission and distribution losses and subsidies have together created a national gaping hole of around Rs.4 lakh crore which state distribution companies must make up.

There are three alternatives before states: first, reduce losses and theft (often mis-declared as agriculture to escape detection). Second, reduce the subsidies. Third, increase power tariffs. The third is difficult as Industry is already groaning under power tariffs of Rs.8-12 per kWh. You cannot have “Make in India’ without making industry competitive. So, the state will have to act on the other two.

To discuss this, the FPJ-IMC Forum organized a panel discussion with experts at the Indian Merchants Chamber, Mumbai. The panel comprised (in alphabetical order) Pramod Deo, Ex-Chairman, CERC; Suhas Harinarayanan, Executive Director & Head of Research, JM Financial; Mukesh Khullar, Principal Secretary-Energy, Government of Maharashtra; Anil Sardana, Managing Director, Tata Power Ltd; and Bipin Shrimali, Managing Director, MAHAGENCO. The event was moderated by R.N.Bhaskar of FPJ with editorial support from Pankaj Joshi.

The welcome address was given by Dilip Piramal, president, IMC, and the Vote of thanks by Deepak Premnarayen.

Given below are edited excerpts:

FPJ: The government is talking of Make in India. Make in India does not become viable or feasible unless industry becomes competitive (internationally), (and) if the pricing of power is not reasonable.

Moreover, because of the subsidy regime that has been introduced by the government industry has to pay a higher price to cross subsidize all the cheaper power given to agriculturists and economic weaker sections. I would like the panelists to dwell on what the way out could be.

Anil Sardana: Let me start by leading the context. When we talk about tariffs in Maharashtra, I think it’s important for us to understand the perspective in comparison, first of all, to international situation and then to our home markets.

Internationally, in most countries, the industrial tariff for economic reasons is actually the lowest tariff, and then the rest of the tariffs are away from average cost of supply. This is because the basic genesis is that the industry must contribute to economic prosperity and therefore, industries get the most economical and most competitive in terms of tariff.

In the Indian context, I think we have used the tenets of democracy, and kept the vote bank, since everybody ultimately is a residential customer. The residential customer therefore gets the benefit of the lowest competitive tariff, which is the most away from the average cost of supply that means, it’s the lowest from the average cost of supply.

In order to make things manageable, the industrial tariff is pushed up, the commercial tariff is further pushed up, which makes the two almost unsustainable in two aspects. One, the industry bears the brunt of paying higher for the raw material called power.

And number two, we have done a study– since I am also the Chairperson of CII –and found that in the five largest power consuming industries, if you compare with those five manufacturing sectors internationally – let’s say steel, cement, chemicals and two others large consuming sectors – Indian power tariff to those industries, which is like the raw material, are at least double, if not more when compared to other competing and competitive countries.

Read more on next page

So if you talk about, let’s say, steel and you say, let’s compare steel costs with China. Then the input raw material power cost, to a Chinese steel company, is half of the input cost to Indian steel industries. And similarly this is true for chemicals. Similarly this is true for other metals and commodity companies.

So I think the important point that needs to be understood by people at large, is the tariff setting, which is done by regulators, which are independent of the government. They have by and large pursued a similar mandate, as the government earlier used to have, which is to appease the residential customers, which is to appease the vote bank, and have kept a very large deviation from average cost of supply.

Now, many people sitting here must also understand that when the tariff is talked about and since the subject is, will the tariff become competitive, one must understand that in the tariff formulation about 75% of the tariff is bulk power cost. The balance 25% is the cost of the distribution company, or the transmission, billing charges etcetera, etcetera.

And therefore, the only constants which will impact whether the tariff will go up down is largely the bulk cost, bulk power cost and not the costs of distribution company etcetera, particularly if there are no losses. Now since people sitting here live mostly within Bombay, I can make that point that there are no losses in Bombay and therefore there is no impact of that being paid by customers.

But the trend of tariffs in Maharashtra and Mumbai will largely depend on bulk power cost. And therefore bulk power cost will largely depend on fuel increase. And the fuel costs, when it changes, for example when you get to here, the coal cost changes or the other, gas price changes, that impacts the power cost, the input cost. Tariff has to be understood ultimately as the cost of the fuel, because the rest of the things are by and large efficient in the Mumbai context and in the Maharashtra context.

But when we get to the average cost of supply for all customers – that is a mandate regulators must observe – that subsidies must be given, over a particular period of time, to ensure that they are plus-minus 20% of the average cost of supply. But that hasn’t happened. Political interference is still visible.

Most of the regulators haven’t been able to come out of the political pressure and set up tariffs which will have a particular philosophy.

Nowadays, the regulator has no philosophy. In fact there are multi-year tariff concepts in Maharashtra, where not a word has been written on the philosophy behind these tariff structures

So that is the state of affairs today. So for anyone to say whether the tariff will go up and down, scientifically I will only add one last line and then leave it to the rest of the panelists to talk. We are fortunately today in the lowest cycle of commodities. Oil prices, coal prices are all at the lowest level that you can hope and perhaps there is more to follow.

I am telling you that at Tata Power, I am submitting my proposal to the regulator that please reduce the tariff across the board by Re.1 for Tata Power, because we are at the lowest part of the commodity cycle and there is room for us to do that.

But what will ultimately transpire is in the hands of the regulator, we cannot say. This is because in the last order we found tremendous amount of gaming and a new word that I learned. It’s a word called Migration Economics, which I had never heard before. [The regulator calculates the] economics of migration of customer from one company to the other. If you are lower, I will make somebody else lower so that people shift to the other fellow. If he is higher then I will make you to lower so that people shift to somebody else. I have not heard this.

Read more on next page

Why should it not be based on efficiency and the type of service the particular distribution company provides and why should there be gaming by the regulator?

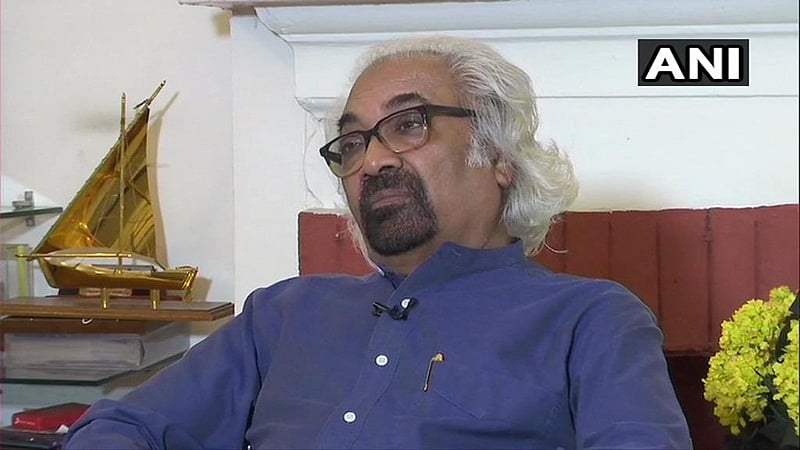

The Free Press Journal and Indian Merchant Chamber organized Panel Discussion Will the Power Tariffs in Maharashtra (L to R) Anil Sardana Managing Director Tata Power Ltd, Pramod Deo Ex Chairman CERC, R.N Bhaskar Consulting Editor Free Press Journal , Mukesh Khullar Secretary Energy Government of Maharashtra, Suhash Harinarayanan Executive Director J.M Financial and Bipin Shrimali Managing Director MAHAGENCO . at IMC Mumbai. Photo by BL SONI |

FPJ: Could we get the views of Dr. Pramod Deo?

Pramod Deo: I’ve been here a number of occasions both when I was in MERC and CERC.

Now, what I would do is I must bring out the political economy of electricity. I’m now going to talk about Maharashtra.

I’m just going to give some figures, based on the MERC’s latest edition. Gujarat is supposed to be a model, Maharashtra is also like that, so that’s why I just decided to study these two. It’s very interesting.

Maharashtra Distribution Company’s overall budget or what we call as Annual Revenue Requirement (ARR) is Rs.55,000 crore. Now you will be surprised that there are only 16,000 large consumers. Do you know how much they contribute? They contribute 42% of 55,000 crore.

Further, if you take one megawatt (MW) and above consumer demand, their number is 180,000 and they contribute 62%. Now, what we have left is 2.10 crore consumers which includes 37 lakh agriculture consumers. They contribute only 38%. So, this is the political economics. It is not only the small consumer, it is also agricultural consumers.

Now, what is the average cost of supply? Today in Maharashtra it is Rs.6.03. The average tariff comes to Rs.3.11, so obviously tariff cost subsidy has to come. Now what happens is that Maharashtra MERC had a mandate — when we started — to increase the tariff for agriculture, so that’s what the mandate was.

Read more on next page

So, we started the first tariff order and after the cabinet met they were asking me we have three members in MERC. [They asked me], “can they not increase the number, can we not get some capable person with a legal background? [What they meant was to include] politicians on the MERC, so that we can have a proper balance because that is the first time MERC had increased the tariff for agriculture. And do you know what was the tariff or increase? Something like around Re.1/-.

Now, today’s position is that MERC puts out a tariff. If you see the average billing rate is Rs..3.11, even [this tariff is what] agriculture does not have to pay because what Maharashtra government does — as the law provides — is to give an upfront subsidy, and that subsidy is Rs..4,500 crore.

And another Rs.4,000 crore plus is the cross subsidy which I talked about. This is political economics. So if you ask me the question, “Is Modi really serious about Make in India?” we have to start with the Chief Minister — since electricity is for all practical purposes a state subject.

This new UIDAI scheme cannot work without political consensus. For that we have to go back to the 1990s when the health of the electricity boards had become a matter of serious concern. [At that time] there was a political consensus and the National Development Council (NDC) had agreed on two things. First, tariff determination will be taken outside the political purview. We will have independent regulators. The second and most important point was that agriculture must pay at least 50% of the average cost of supply.

This political [vision] then obviously broke down, because of Jayalalitha. When the 1998 Bill was brought for setting up the Electricity Regulatory Commission, she said “nothing doing”. “I don’t agree and it shall not be mandatory”. But anyway that is history, and then we went to to the 2003 [New Electricity Act] – a very radical thing.

However there has been no progress on this. And in Maharashtra, we have experienced acute shortage during my entire period as Chairman of MERC. We had Enron, and after Enron no capacity was added. So the result was that we’ve faced shortage of something like 40% and we had to deal with the rationing of power. We had the problem of regulating capacity and the more important question of “how do we address this issue of agriculture?”

The original thinking was that the cross-subsidy shall be eliminated. But in 2005 it was a UPA government, where you had the left parties, they said, “no, no, we can’t eliminate”, so the word was changed to “it will be reduced”.

The obvious idea was that you must protect the small consumer, and in fact, if you do the analysis, protecting small consumers is not at all a problem. It is really the sugarcane, vineyards and banana. In Maharashtra on the basis of my experience of load shedding, these are 8-9 districts which are the real culprits. It is for them all this money has to be given by the entire industry. How are we going to have any kind of “Make in India”? Our CERC analysis shows India’s industrial tariffs are the highest in the world.

This is the picture that shall change. I am telling you this, based on my more than 11 years of regulatory experience, and power sector experience of 34 years.

FPJ: Suhas Harinarayanan, can I request you to make your observations?

Suhas Harinarayanan: I’ll give you some slightly different type of numbers.

First, if you recall about eight years back in Jan 2008, coinciding with what was then the largest IPO in the country – you all know which one it was – the valuations for some of the power stocks, for example, for NTPC, had gone up to nearly three and half times price to book-value. Book-value is what is the investment or net worth, on which you want your returns. And the price to book value is now about half that number.

Some of the IPPs, the Independent Power Producers, around those times were trading at four to six times price to book-value. Some of them don’t have any book value now, so they’re probably at negative infinity to put it mathematically in a correct fashion.

And, of course, the Reliance Power IPO, then the largest IPO in the country, was oversubscribed 82 times, so which meant that investors were willing to put in about $25 billion into the power sector in this one company. Right?

Now, what does all this mean in the current discussions? Mr. Deo spoke about the political economy, Anil [Sardana] spoke about various other issues.

I think one part of the discussions we are having, is that the power sector is obviously the biggest contributor to the NPAs or the stressed assets in banks. Power assets, or the power sector, constitute about 9.4% to 9.5% of total advances, while they account for about 34% to 35% of stressed assets. That’s almost ratio of 1:4X.

You could give various reasons like the loss-making statements, the Boards, the coal shortage. But there is another reason, the demand/ supply situation in the country. From a peak deficit of 12%-14% about 5-6 years ago, the deficit has come to about 1%-2% right now, whatever the reasons. But basically there is more power than what is being demanded at this point than it was around 6-7 years ago.

The spot rates for power have fallen, more than halved, from double-digits to mid-single digits, even lower than that. And there is lot of debate around whether the real GDP is 7.4%, 5.8% or 6%. Let’s assume its 7.4%. Let’s assume it grows at the same number for the next five years. Ascribe a GDP multiplier and consider all the additional capacity which is coming up, with enough coal being available. We could actually have zero deficit in the next five years. The power deficit could actually fall to nil in the next five years.

Now that’s a substantial number, in the sense that you’re falling from 10% about five years back to almost nil deficit in the next five years. Now would such a sharp increase in supply mean that tariffs actually come off?

Read more on next page

There are other things to consider also. I was reading some articles that in Germany the utilities – I don’t know whether it’s a Christmas special gift but the utilities were actually paying customers to consume electricity. Negative tariffs. Right. Part of the reason is, of course, during Christmas the demand comes off, industrial activity comes to a stop, but there was also excess renewable energy production. There is reasonable amount of wind energy produced during that time. So utilities were actually paying customers.

Another reason was, Germany being the leader in giving subsidies for renewable energy, due to which a substantial amount of solar rooftops had come into the country as well. And as was stated, industrial tariffs in Germany are lower than residential tariffs. Suddenly you had residential tariffs being lower than industrial, because of all these residential rooftop installers who stopped buying power.

Now, in India, some recent bids on solar have been very aggressive. Actually in many states, I understand they are lower than the residential tariffs for the very high consumers – people who consume maybe more than 500 units etcetera. So, rooftop solar prices are actually lower than the residential tariffs.

Along with higher thermal (power) supply, we’ll also probably have a lot more solar (power supply), that’s another reason to expect that overall tariffs to come down.

Lastly, let’s assume that if the technical and commercial losses which are as high as 30% in the country, even if they can fall, that adds straight to the capacity. So, there are enough drivers for overall tariffs in the country to come down. But, which also clearly means that we are probably not going to see another $25 billion flowing into power sector anytime soon.

FPJ: Could I now request Bipin Shrimali to give his observations on this situation?

Bipin Shrimali: I am a bit of a misfit for this panel because I am a generator not basically from a distribution company. But still I too have a few concerns.

As you know, any tariff has basically three components; Generation, Transmission and Distribution. Generation basically does not have losses, but the major component of the expense in power generation is fuel, which is around 80% of total cost of generation.

Transmission does not normally carry any expenses except billing charges and maintenances of substations and so on. The distributor is the real company where all tariff issues come up.

[It is important to take note of the] average purchase price – the price at which the distribution company purchases power from the generation company. Then you add the transmission cost and own administrative expenses plus any T&D losses.

In Maharashtra average purchase price is Rs.3-3.25 per unit, and the distribution company sells it to consumers at Rs.6, almost 70-80% away from the purchase price. This is the crux and consumers need to understand why this is so.

Though I am not a person from a distribution company, till last month I was holding the additional charge as MD in the State Distribution Company as well. So I know a bit about that. Operational efficiency is the most important thing in distribution, which comprises technical efficiencies, and administrative or other costs [or inefficiencies]. Transmission losses are 4%-5% but in Maharashtra, we have around 18% of total losses. So that’s 13- 14%, which gets added to the tariff beyond the average purchase price. This is the one issue which the distribution company needs to tackle through technological intervention, competency or operational efficiencies. And there are ways and means.

Collection efficiency is good in urban areas. But there are certain districts, there are certain clusters of villages – I would not name the districts – which for years together have not paid electricity bills. In this scenario how would you expect to cross-subsidize these tariffs?

As far as generation goes, there is basically nothing in our hand except operational efficiencies because 80% is my fuel cost.

Let us look at fuel cost, say in Maharashtra. MAHAGENCO is one of the largest power generators in the country, next to NTPC, and 80%-90% of our capacity is thermal power. Fuel input is coal and coal prices are determined and notified by the coal ministry.

Another major component is freight, which is again determined by railways, not in the hands of the generation company.

So, very little is left over for operational efficiencies, by way of say improvising techniques and technologies, technological intervention in maintenance also. For example, in MAHAGENCO we have seven to eight major thermal power stations like Nashik, Chandrapur, Koradi, Khaperkheda and Parli. And in Koyna we have a major hydro capacity. We have some 35-year old plants, and some which are age-old plants of say 210 MW. Nowadays the latest technology is of 660 MW and above which are called supercritical power plants.

The specific coal consumption again ranges from 0.45 or 0.5 to 0.78 up to 0.8. Among my own plants I have some which have coal consumption of 0.7-0.75.

So overall it is not generation, but distribution, which plays the major role. There, the regulator and the government, by way of policies and by way of their subsidy, come into the picture.

Read more on next page

FPJ: So it is clear that the key players in determining tariffs are the distributor and the regulator. So why can’t distribution be tackled the way Bhiwandi was? Bhiwandi was where billing and even collections were not done, and where losses were huge. So the government decided to privatise distribution for Bhiwandi, and Torrent took it up. In a couple of years, it was profitable, billings went up, collections went up. If there are losses shouldn’t that be the first answer to losses?

PD: You see we have to understand that when you talk about distribution companies. They are entirely owned by state governments.

FPJ: Except pockets.

PD: No forget about those legacies… Mumbai, Calcutta, Ahmedabad, Surat — for historical reasons. Thus, Delhi was the only place where privatization took place. Orissa was the first experiment – the World Bank put in all the resources, but the outcome was a complete disaster. But, in Delhi, Kejriwal has come and obviously we keep reading different interesting things.

But coming back to distribution companies, the most important thing, is the pernicious practice which had started. I remember I joined the IAS, in 1972-73 when I was under training in Osmanabad district, and this great thing happened, Maharashtra Government had decided that there would be no metering for agriculture, it will be on horsepower basis and that was the revolution. That revolution has spread all over India and we have no metering for agriculture.

The only place a solution was found — what Gujarat talks about, only it’s not Gujarat – was Maharashtra. The simple thing in predominantly agriculture districts is – how do you regulate in a power shortage condition. You don’t supply agriculture (for the entire) 24 hours. This is not possible and your whole system will collapse. So you supply for seven to eight hours. For that you should have a separate feeder and that’s what Modi has been talking about. Therefore in Gujarat now I can supply 24×7 electricity to villagers, and also to small industries (like) dairy, poultry; otherwise they also used to suffer.

When we talk of the All India figure of 27% Technical, transmission and distribution losses, that figure is not reliable at all. It’s only when you do the feeder separation, then you know what the real losses are. Because the simple thing which is clear to anybody who has taken mathematics, (is that) if you have two variables you can always keep changing those variables. This was the actual nightmare as the regulator and MSEDCL used to keep changing this figure.

FPJ: I see. . . . .

PD: It is only now that you have a separate feeder. Still they have resistance towards automatic meter reading, which is apt and which will finally happen. The difficulty is, we really do not have a measure of what are the losses — and what is aggregate technical and commercial value. Forget about transmission losses. Transmission losses are 3% to 4%.

FPJ: I agree.

PD: Those losses are clearly technical, nothing can be done. The real losses are cases of theft of electricity, wrong billing, no billing.

There is also a very interesting category, “consumer missing, permanently disconnected”. But permanently disconnected means he is there, he is consuming electricity, but somebody else is paying for that.

That is the real issue, and it happens because it is owned by the state government. Now what happened in Bhiwandi? Bhiwandi had losses of 65% plus at that time. So this great experiment came into operation.

At that time power-looms were the key consumers in that area. Since they were also treated with kid gloves like agriculture, they did not have meters, but were given billing on horsepower basis. Then metering was introduced, which they didn’t want, but they filed a petition with MERC that we want meters, but we have not been given meters. Be that as it may, losses were what happened. When Torrent took over, the power supply quality was so poor that the looms could not run without interruptions.

Torrent understood the business philosophy, and rather than go and ask for bills, they just aimed at improving the quality of supply. That time itself, there was a big breakdown in the transmission network – nothing to do with distribution – because MSEB had neglected the transmission assets. After all, the area was a gone case, so why spend money on that. That was the time Torrent engineers stepped in.. But here the Maharashtra Government gave administrative support and police support to Torrent, and Torrent could improve the supply.

So in our public hearing, there was initial resistance from Bhiwandi consumers about giving [distribution, billing and collection] to a private party, but it dissolved due to quality improvement in one year. That also coincided with the economic boom, where all the power-loom-walas realized that they could make money. So they started paying, and, from that loss level of 65%-70%, today we are talking of 36%.

That is the real story, but it cannot be repeated unless you get Government support

So it may be a solution since politically that is acceptable, because I can’t imagine any Chief Minister saying I am going to privatize distribution.

FPJ: One question. You were a regulator; can’t the regulator insist that wherever there are losses, it must be given out to a private distributor if the government can’t manage those losses?

PD: As per the law, the regulator is not into the issue of ownership, it can only focus on given targets. Finally, you face reality. In this context, in Maharashtra, the authorities did a very interesting experiment. First time this issue came up – what are the real losses?

In the First Tariff Order which MERC had come out with, they said the losses are 34%. So that time I think MERC was very unrealistic. They said that you must bring down to 25%. So, obviously, according to the 2002 Order, you can’t bring down losses by 8%. The 8% loss reduction is just not possible.

Now what do you do? So a sharing formula was derived, wherein 50% would be to the account of consumers and 50% the MSEB would bear.

Read more on next page

But the losses cannot be uniform across divisions –basically districts — both are more or less synonymous. So wherever the losses are more, there the consumers will have to pay a higher tariff, was the call. This judgment has been upheld by the High Court, And the High Court has upheld it, because when I was there in MERC we justified it.

The same principle was applied when Maharashtra faced power shortages. We said that if you are having high losses, you shall go without electricity for longer hours because we have to anyway share shortages. So the entire Maharashtra urban and rural areas were categorized into A, B, C, D because the criteria has to be different, because rural will have more losses.

So that formula came into force. People became conscious. They started asking – and we also proposed – that why don’t you then have a system of reward and punishment for the employees. And the best punishment for an employee of MSEDCL would be to send him from an executive position to non-executive position. Then obviously he can’t make money, which is a key factor.

In that Bhiwandi instance I must tell you how money is a big factor. When Bhiwandi was taken over by Torrent, the condition was that, you must take over all those SEB employees. So they were given the option. Torrent offered 60% for technical staff as a bonus – 60% more than what MSEB was paying.

Would you believe it? Do you know how many engineers that time joined? Only 25% agreed to go and all of them have come back, because life is difficult there. In MSEB life is much better. Another thing is when I was in MSEB; I found that there was a record where a junior engineer owned 12 power looms.

So obviously it is completely a case of ‘waste’ management within the system. How do you deal with these people? That’s why I say, it is a political case and unless you can understand this, you can’t understand wwhy privatization is difficult. How do you privatize? Ground difficulties are again different. Few private players would like to take over the rural areas. They won’t be able to handle it. Because in the rural area, the local politicians tells you how to load that transformer.

FPJ: Any more views?

AS: Let me use this opportunity to dispel some of the myths. First and foremost, the biggest myth that exists is that the maximum losses happen in rural areas and in agriculture. It’s completely false.

The second biggest myth is that un-metered electricity by slums causes biggest losses. It’s a myth, it’s wrong. I was the person in Delhi. When we took over we had 53% losses; Rs.1,500 crore was the billing value stolen every year in our area. Today the losses are 9%.

It is not by virtue of those slums, it is not by virtue of the downmarket people, but due to the prominent people; it is by virtue of people who matter.

The irony is that you know many bureaucrats, many politicians take umbrage at such remarks. I want to say this because I have very open-minded friends sitting here. They make the charge that it is agriculture, it is the slums which are stealing electricity. But no, it is the large customers who steal electricity. Why? Because it is the staff which connives with them; tells them that if you do not give this, I will be vindictive against you.

I have seen those cases. And therefore I’m telling you as long as government is in the business of business, you forget about it. We have used up 70 years since independence. [We can travel] another 70 years, we can keep discussing this. Nothing is going to improve.

Electricity is not a rocket science. Electricity in Mumbai, Calcutta, Delhi – and other places – can be delivered 24×7. We took over Delhi in 2002, we’re talking in 2016 today. Thus, 14 years later nobody has any inverter, nobody knows how electricity was being offered in the past. Today, electricity is 24×7, losses are gone. Simple point is, government should take the whip and get the work done by the private sector. That is the government’s job. If governments themselves get into business and a junior engineer will retire as a junior engineer, what will you expect him to do? He will earn out of the business itself and that’s what we saw.

So according to me, whatever we keep talking about, the fact is today, if the State Electricity Board delivers electricity for whatever hours, it says “I am obliging you”. That is the spirit currently. This has to change to a service obligation. If you have to deliver to the customer it is your obligation to deliver 24×7.

If you don’t deliver, there should be fines on people. [Unfortunately], those fines can’t be put on government employees, it’s as simple as that. So how do you expect those government employees to change and deliver services to customers?

So the simple point according to me is [don’t] blame government, [don’t] blame the system. It is simple. The government can get the best work done out of the private sector. They should take the whip out and get the work done. But you cannot regulate a government sector.A Regulator cannot regulate the government sector. But he can regulate the private sector. Therefore, you should have the private sector, so that the regulator can regulate them and get the desired efficiency for customers.

So I’m saying ironically, we must actually tell the politician, the time has come. It’s been 70 years since independence. The customer needs better service, the customer needs competitive tariff, industry needs to survive, industry cannot survive, Make in India cannot happen unless the basic raw material is available and at a competitive price. So I think there’s been enough of discussion, we should now do a paradigm change and get to the brass tacks of saying, electricity has to be delivered 24×7 — no questions about it. And it is to be given as an obligatory service with the customer as the focal point of delivery. Full stop.

SH: I think I share a lot of the views expressed. In our world we call the whole SEB [state electricity board] issue as India’s famous seven-year itch, because in 1995, we first saw it coming — because (that was) when the first round of IPPs came into the country. 2002-2003 you had the itch and you had an Electricity Act as a fallout of that. Again, it came up in 2009-10. So it’s come back again in 2017-18. So this is why we call it India’s Seven Year Itch.

So I think it’s actually frustrating for investors. At this point of time there are many investors who’ve taken a view on India and also on the Indian power sector, because as I had mentioned, 35% of India’s stressed assets are from the power sector.

So unless that really revives, you really don’t see a lot of the other things falling in place. You won’t see growth and honestly don’t believe that 7.4% real growth is possible. There are some reports saying that it’s more like sub-6%. But, clearly, that growth is not going to come, whether it’s Make in India, whether it’s other aspects of growth.

Read more on next page

So we need to see this movement [from losses to profits]. It is good to see Tata Power getting losses of 53% down to 9%, I don’t think it’s been achieved anywhere in the world So, full kudos to him [Sardana].

I think investors are watching this space extremely closely and there has to be action this time around. Otherwise, as I said, you know, this 2016 through 2023 – the seven year itch – will revisit us again.

BS: I would just like to comment on one issue — that government intervention has to be there always – maybe how you take it is a different thing, positively or negatively. But since 1992 there has been a pro-privatization move in India and we all have been witness to that. And the 2003 [New Electricity] Act which involved the total revamping of the Indian Electricity Act, it is also, you can say, the whip of the government.

So at all levels, state level or central government level, all successive governments have had always this thing into their mindset, irrespective of any party.

But as Dr. Pramod Deo said, there is a political economy and it has also to survive, because we people sitting here we may have different things have our priorities and our mindsets. But after all government has its own priorities. And its not only the political economy, but lots of other things also. For example, you see the civil aviation sector, where, either on BOOT basis or in the form of privatization. It has been handed over at a few airports and you can see what is happening there.

And a few years back, when Dr. Kurien was in NDDB, there were some interesting events in Gujarat. I come from Gujarat, and incidentally I’ve worked with the government of Gujarat also. So in the 1980s, when the edible oil prices were really skyrocketing, at that point of time government of India told the NDDB to procure edible oil – and more particularly intervene in the market with the procured oil. When NDDB did so, edible oil prices came down. So this is one way of looking at the system.

Government intervention is always needed, but at what level, and in what context and in what content, that is more important.

But I do agree with the views expressed that this [distribution] is not the real business of the government. Government has to be there only with market intervention at specific points of time. If the electricity sector were to be totally left to the private sector, then what will happen we don’t even know.

FPJ: We have stressed assets in the power sector of almost Rs.4 lakh crores. UDAY [Ujjwal Discom Assurance Yojana] has been introduced, but that only takes care of past borrowings, it does not restrain any government for making future losses. Now what can be done to reduce the losses?

What can be done to remedy the situation — both for employment generation, which means industry vibrancy, as well as for full power generation?

AS: I think Dr. Deo mentioned that UDAY as a scheme does not really offer a sustainable solution. You also mentioned that point. So the more important point is that time and again when we dole a check, it is only because it is public money, good money chasing bad. About every 5-7 years it is Rs. 1,00,000 crore or 1,93,000 crore and now again a similar amount of money is being rolled out, without somebody being answerable to the fact about when this will stop. So, I think that the consequence management of the fact — that is this the last time that this is happening — is just not there. That is the first part of what I want to mention.

The second part is — of course, I keep saying this and I want to make that point again – that electricity is a very simple subject if you don’t complicate it.

It’s a very complicated subject if it helps you confuse the issue. I think that the second option has been adopted today — that let’s keep confusing the public at large, so that we can manage to do what we wish to do.

And I think that’s what has been happening. You know, you complicate the tariff to an extent that no consumer can understand tariff formulation today. I am telling you it’s so complicated that even you take it to your board members and after five minutes there will be a veil, because nobody will understand how it’s been formulated.

Why? It should be very simple and transparent to say, this is my bulk cost, this is my cost of O&M and this is my ROE, this is what I am going to charge you and that whole thing should be transparently available like it could be done in a spot market. It could be done online, it could be done anytime. Consumers should have the choice to buy, the way he wants to buy.

I am telling you — in Delhi we tried. And I want to give you this beautiful example of commoditized electricity. We had actually done it, but the regulator stopped us from doing that. I came out with smartcards and said this smartcard is Rs.501 rupees, this is Rs.750 rupees, this is Rs.1001 rupees and we went up to a denomination of Rs.2500 rupees and said now you gift electricity to your sister for this Rakhi festival or gift electricity for Diwali.

What we wanted to actually do was to engage with the customer to say that electricity is like any other commodity. If you consume you have to pay for it and as simple as that. That you have a card, you insert it in your device which we gave to everybody’s home and say you put it in the plug and put that card and you can consume electricity till that time that there is money in that card.

Now all of this can be made so simple. So like the way you buy your set-top box air time today for your TV, I can give you electricity the same way. You can buy from me or you can buy from them. or you can buy from anybody. Because electricity when it flows from the wires doesn’t see the character it has come from. But it can actually have an engagement of a contract.

So you can buy cards and people will have different rates of electricity from different people and you can buy according to your consumption. So I am saying a lot can be done provided it’s open to do that. But today it is not open to be done for the simple reason that it helps some of these sets of people to be [opaque].

So, if you want to see standard assets being dissolved, over a 1,00,000 crore, a bank is to be brought back into the system. You will have to unpeel the system. You must make it simpler and unpeel the system so that the market dynamics start to take over. Those who lose the money lose it forever, those who don’t deliver on efficiency lose that money, those types of criteria have to be set, number one.

Number two, the distribution company is like a shop. Have you ever seen a shopkeeper, a merchandise seller, being defunct? Who will supply him the merchandise? Today the distribution companies are defunct and therefore by virtue of that, a lot of other assets will become defunct naturally.

Because neither is quality demanded of them, nor is being competitive. The whole value chain is going to become defunct. It is happening. You are seeing the early signs. Very soon even those assets which are competitive are liquid assets.

For example, let’s take, UMPPs [ultra mega power projects], which are supplying electricity, let’s say, at Rs. 2.30 or let’s say Rs. 2.50, they are very competitive. But they are supplying to five customers, out of which, three have already been declared brain dead — assume for a minute. How will they give me money for even running at Rs. 2.50 a unit asset?

Because the fact is that they don’t even collect. They collect 35% of what they should be collecting. So they have 65% losses in one of those states. I’m just trying to tell you in the actual sense. It’s a different matter if you add subsidy to that, because they use subsidy as an element to declare lower losses.

So, the reality behind the veil is that we are creating a sector which is going to become unviable because the shopkeeper who sells the merchandise is unviable. So make the shopkeeper viable before everybody else who supplies the merchandise to the shopkeeper also becomes sick. I think that’s the simplest way to understand.

PD: Another aspect is that the liberalization in 1991 did not see much happening in the electricity sector. I used to deal with private sector participation in electricity in the power ministry, where the idea was just to have more Tatas set up generating stations like NTPC and to supply to the same bankrupt SEBs. I had to work on how to make that attractive. Even the 1998 Electricity Regulatory Commission Act did not talk about privatization at all. It was the 2003 law, which talked about it, but again obliquely. If it talks about privatization – as if it will happen. The reality that electricity distribution business is a natural monopoly.

FPJ: Yes, it is a natural monopoly.

PD: So in a natural monopoly, how do you bring in competition? In telecom it happened because you had a product — a mobile phone — which really broke ground. You broke free from wires. Then you had two or more service providers and consumers could choose between them.

But in electricity, you can’t have parallel networks because it’s very expensive and so the 2003 law talked of open access. The whole idea was the consumer of one megawatt and above after a certain period will have a choice to buy from anyone. But because of this element of cross subsidy, no electricity board would allow that.

And even when regulators failed in that, we could do that, but only in a supply shortage situation like in Maharashtra. Here we told industry that since we can’t anyway supply you with power, if you can buy electricity from anywhere, it’s fine. So this way we made the cross subsidy zero. But after that nothing more has happened.

Unless we can build in competition, what would the model be? In the so called new amendment, the separation of carriage and content, nobody is addressing the political issue. That separation of carriage and content, well you can always have somebody who will be carrying those lights, building those lights but when it comes to supply, it means that you have to bring in the private sector.

Are you really ready to do that? What about the cross-subsidy? This amendment was introduced in December 2010 but luckily, what has happened is that the parliament is not functioning. I just don’t see how it’s going to happen. So again, we come back to remembering that if we want electricity supply to improve, there has to be competition. And how do we bring in competition is the big question.

Tariff can come down. Today we have a very absurd situation where in India we have more than 2,70,000 MW of established capacity and the peak demand is some 1,42,000.

FPJ: Capacity is already there.

PD: No, the simple reason is the Kejriwal analysis. Nobody wants to buy electricity, because tariffs will go up. So the best thing is don’t supply electricity and keep tariffs low. Only thing is that in a city [setup] it doesn’t happen, where tariffs are going up. So the main issue comes up again. How do you bring in competition and make electricity a business, not a government appendage?

SH: Some of this is music to our ears. Privatization making a business case out of power. There have been failed models in the past, but I’m happy that many of the investors we speak to are not in this hall. Had they heard today that UDAY is not going to work, or going to take a long time to work, they would probably walk out of the room and sell their shares.

On a different note, I think Dr. Deo mentioned about this 270,000 megawatt or 300,000 megawatts of capacity. Instantly, as I understand, total industrial demand is possibly 25%-30% of that, which is about 75,000 to 100,000 megawatts. A lot of the new capacity is coming up – 2012 to 2017 or probably up to 2019 – all this will be equivalent to that. So combine that with the open access. A lot of the owners of the upcoming capacity actually haven’t tied up their PPAs – I think at least 50% haven’t. So why can’t a new capacity be fully under open access?

AS: Suhas, unless you address the electricity economy issue or the political economy issue, and bring the tariffs to nearby average cost of supply, the moment you give open access, the existing capacity will be left with customers that are so much lower than the average cost of supply, that existing players will be dead and over.

So the political economy will virtually make the state electricity board collapse. They will not be able to service any customer left out with them. Hence a precursor to making this successful is to course-correct the pattern of tariffs. If you don’t course-correct you are basically in for another colossal issue.

SH: Fair point – there are two ways possible to get things done. One is by pushing from this side and the others by pushing from that side. I was probably talking of that side, where you throw the stick first before the carrot. And yeah, open access is the much discussed idea which has never been born, ever since the 2003 Electricity Act came into being.

It will be wonderful to have privatization at least in some of the largest cities. Again, starting from the other side rather than trying to tackle the losses. I think investors would love to get such ideas.

BS: I completely agree that tariff structure, the computation of tariff and lot many provisions need to be properly simplified. Sometimes it is difficult for even us to understand how the tariff is worked out, with so many complex formulas and if it is the case with companies then what would be the case with consumers?!

Second, the tariff structure and the formulations are similar in civil aviation or in a mobile [phone] bill which also have the same complexities, so many charges.

So basically the service provider, maybe in electricity, telecom or maybe in civil aviation sectors need to have the same approach [to simplify tariffs]. Whatever be the actual price of the offering, a lot of things are added on. That needs to be property tackled, to be properly monitored at appropriate levels and by the appropriate authorities.

FPJ: Okay. Questions from the audience.

Audience: As of now, there are 84 tariff categories in the country, why can’t it be only 4? Residential, agriculture, industrial, commercial – they can go to the open markets. And agriculture and residential sector why can’t they be on a uniform basis? Residential consumption in this country can be supplied by NTPC alone.

FPJ: Excellent.

AS: Regulator.

FPJ: Regulator? Can we have your answer?

PD: In fact, we tried to reduce so many categories, but issues cropped up like how can a hospital or educational institution be categorized in a particular slot, why not give them a separate slot, and that’s how again the proliferation starts.

As far as agriculture goes, as I said, the agriculture tariff is not metered. You have to start metering. That is the first simple thing. I’ve told you we have 2.10 crore consumers in Maharashtra wherein 37 lakh are agriculture. Now if you were to remove that, out of these 2 crores those who are using simple two, three bulbs; you can give them LEDs today. And one or two fans. And everybody now has a TV. You can work out their demand. Then it is easy to supply that — from the lowest category – as part of your power purchase agreement, what we call a lifeline supply. The problem comes is as you go higher up and all the leakages which take place…

FPJ: Leakages are the big problems.

PD: A huge problem — and that’s what we are really talking about. So it is not the category, but categories get again multiplied because of this constant pressure. Now why should a hospital like Lilavati be given a special listing? It’s supposed to be charitable, but I don’t think you will be admitted there.

FPJ: Can we have the second question?

Audience: Would it help if the Electricity Regulatory Body of a state has more members from the producing companies?

PD: The question is of more producers? Your NTPC has a 50,000 megawatt capacity. If you were take MAHAGENCO (etc), these are all technocrats. You can have those technocrats around the MERC or the CERC. But how can it help because after all they are the part of that system.

Again, why are IAS Officers being appointed? Because at the ridiculous salary the regulator is paid, why would Anil [Sardana] become a regulator? But it is possible that the private sector can depute someone, his wife can be paid the full salary and he can take the paltry salary and work as a regulator. After all if we are talking of the persons who should have the experience and integrity, they should do that.

In fact, there are some Regulatory Commissions where we have technical teams from within the industry.

We have to have one technical member and normally the technical member in the State Regulatory Commission should be really from distribution, because that is the real thing. When it comes to CERC, anyway there is a very clear categorization, you must have a technical member. Normally you should be from the transmission, which becomes very important when you are talking about inter-state.

SH: I think you probably won’t have to wait for long, because I don’t think the job situation of the country is so great that you won’t have many private sector guys moving to the government sector in coming years.

Audience: I’m really impressed with Mr. Anil Sardana when he mentioned that the smartcard has been issued in a city like Delhi. I would like to ask, why is it not issued in the rest of the country? It’s innovative, a very interesting marketing initiative and a very convenient and consumer-friendly aid.

PD: We have a body called Forum of Regulators where all the Chairpersons of the State Regulatory Commissions are members and I, as the CERC Chairman, used to head that. We did this study when we were issuing this prepaid card. On the legal issue we got the Solicitor General’s opinion which was also in the affirmative. So it is possible.

But for implementation, it is the State Regulator. I cannot say why the State Regulator cannot do that. The State Regulator finds it very difficult to introduce such a thing, that’s the simple reason.

AS: I think the sum and substance is the openness in the mind of regulators and their understanding with whole system.

Understanding options, derivatives and all these types of instruments is something which happens only when the market dynamics are very openly embraced by the authorities. It’s happened in the fiscal sector, why should it not happen in the power sector?

There are also issues like even bulk power be traded on a long-term basis. This is something which has been hanging for last many years unresolved. Why should we not be allowed to make commitments of 15 days ahead, and why should we only be trading power on a day ahead basis?

All of those issues today have lots of mental hurdles. As I said, this area has been made so complicated perhaps because it suits some people. That’s what I can judge, because I have not understood why it should not be made simple. When those instruments are there in the fiscal market, why should those instruments be not here in the power sector?

SH: Yes. In fact, it’s very correct.

FPJ: We’ve been discussing stressed assets. We were discussing ways in which we can reduce losses in the system; ways in which distribution can be managed more effectively so the connections take place properly. What do you think can be done to remedy the situation in terms of the stressed assets on one side and improving collections and preventing leakages on the other?

Mukesh Khullar: This is a situation, especially all those merchant thermal stations, I guess, that is what you were alluding to . . .

FPJ: No, I am talking about the losses that the distribution…

MK: Oh, that. Normally, our losses are in the range of about 18% for the state as a whole. Rural areas are certainly contributing more to these losses. And if I look at the collection efficiency there too the rural areas have a lot to contribute.

FPJ: Are you metering the rural areas?

MK: Not all, but 60% I think are metered. For the rest – there is a process which the regulator has asked us to implement. So, once that is in place, we are running a good system to really measure the consumption.

FPJ: By when do you think this will be over?

MK: Another four years, I think.